Advertisement

Commentary

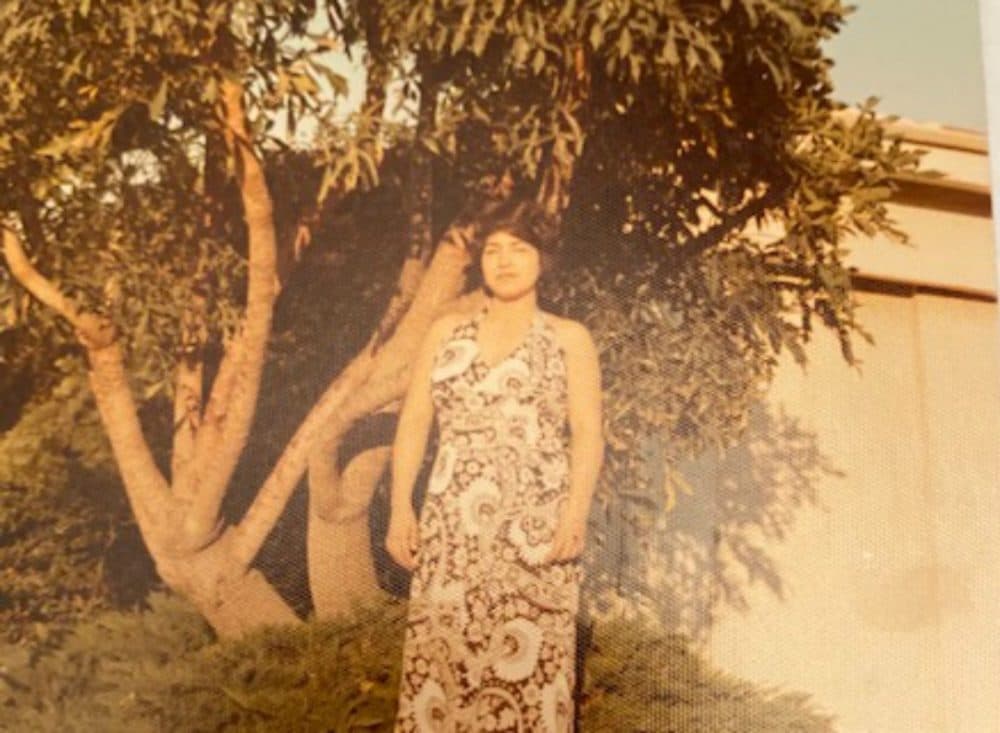

My Mother, Who Could Have Been So Many Things

In restaurants, she always asks for them to reheat her soup. But when the waiter or waitress circles back to our table, I always say, “It’s fine, thank you.” She likes everything hot — her coffee, her rolls at Bertucci’s. Except, she loves just as much an air-conditioned mall. She will stay there for hours, chatting with strangers, salespeople, the perfume lady in Macy’s who gives her free samples, the same women whose eyes I avoid when I pass through the make-up section.

She grew up in Guatemala City. I grew up in a Boston suburb. She could not finish high school in Guatemala. I am a college professor. She hates tests. I do, too.

When my older sister was a senior in high school, my parents attended a GED prep course info session one night. They came home and my father announced that the prep course was too much trouble. “We’re not going,” my father said. “What do you mean we?” my mother responded. She attended the evening prep classes and eventually took the exam. The morning of the test she prayed, ate a good meal (hot) and she did it. She passed. That summer she borrowed my sister’s cap and gown and posed for portraits at the Sears studio in the mall.

When she was young and still, now, reaching 70, she loves clothes. And pictures. And jewelry. And babies. And donuts. And shoes, even if they’re a size (or two or three) too big. She doesn’t care. And feeding people. She loves this the most; it’s her love language. Just the other day she gave the manager at the private pool a homemade taco and he said, “Thank you, Dora. I was starving.”

She could have been so many things. A talk show host. A principal. She is irritated when young people don’t “take advantage” of being in America, of their citizenship. They can apply for college loans, they can start businesses, they can buy and sell property so much more easily. Isn’t each generation supposed to struggle less than the one before? Is that the same as doing better?

I don’t know how to dance cumbia and she does.

I don’t know how to make caldo de pollo and she does.

I don’t know how to clean a bathroom that well. I take too long. If I suggest using Clorox Wipes she shakes her head (too expensive!) as she uses any old spray and an old towel she’s cut into fourths. The bathroom is gleaming in 90 seconds.

Everything can be cut. She cuts coupons and hair and a whole chicken with such ease it’s like she’s a magician. She could have been many things.

If I could sew I would do it passionately. But I can’t stitch a hole in a pair of pants, never mind a button. I ask for her help and she shakes her head, but smiles secretly because she’d rather her daughter not be able to sew a button so she can help her sew that button.

Advertisement

My mother, who could have been so many things. Without her sacrifice, her struggles, I would not be an author.

When she was 18 she moved to America. When I was 18, I went to college in Connecticut. The morning she took a flight from Guatemala City to Los Angeles, she had pressed her hair and then curled it into even waves. But no one was there to greet her at the airport. The family she would work for as a live-in nanny wasn’t there to pick her up; they’d gotten the time wrong. When they finally did pick her up and drove home, my mother remembers being shocked at seeing homeless people on the sidewalks in Los Angeles. In America.

I remember teaching her that you can’t say la negra or la china. You say Black or Asian. I remember insisting that I wasn’t on drugs after I got an eyebrow piercing at 17. “Your body is the only thing you ever actually own. Treat it with respect,” she said. I don’t remember her ever talking to me about the birds and the bees and tampons and birth control, not in the way mothers did with their girls on TV. Bra shopping was something American mothers and daughters did together. Instead, white bras just showed up in my top drawer. I do remember that my mother used to show up at restaurants or parties, checking to see if I was where I said I would be. My face and neck would turn pink upon seeing her and the hostess pointing.

She takes her coffee black. I can’t drink a drop of it without creamer. Her cell phone apps are a mess. Mine are too. She talks too loud. I laugh too loud. But in the movie theater, I am quiet as a spy, opting for Raisinets that I can suck on silently. She talks to the screen and chews popcorn shrimp, taking five-minute naps throughout the film.

At weddings or fancy functions, she’ll talk to anyone and everyone. She is the engine in a room full of people that transports it to a party. Inevitably, by night’s end, I am referred to as “Dora’s daughter.” And then, always, before leaving, she’ll wrap a brownie or an hors d’oeuvre in a napkin and stuff it in her sequined purse.

Once, years ago, when my husband and I were trying for our second baby and needed to borrow money for an IVF treatment, she gave us a brown lunch bag full of cash. We have two kids now. Our boys call her Abue and Abee, short for Abuela. She lives 10 minutes away and sees them almost every day, and when she does, she hugs them close, closer.

This year, 2020, makes it 50 years she’s been in America. It’s also the year I publish my debut novel. This book is her book, too. My mother, who could have been so many things. Without her sacrifice, her struggles, I would not be an author. Because of COVID-19 she can’t have a party. Neither can I. Still, with every breath, we celebrate.

Jennifer De Leon's debut novel, "Don't Ask Me Where I'm From" (Simon & Schuster), was released on August 18, 2020.