Advertisement

Commentary

This School Year, Low-Income Students Will Suffer The Most

In June 2019, 17 parents and two community-based organizations filed Mussotte v. Peyser with the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, arguing that the state had violated its constitutional duty to fund public education. This funding deficit disproportionately harmed low-income students, immigrant students and students of color, contended these families, the Chelsea Collaborative and the NAACP New England Area Conference. The lawsuit cited years of disinvestment and discrimination in the families' public schools.

In painstaking detail, the families -- from seven low-income districts -- described the inadequacy of their children’s education and the enormous gaps between the haves and the have-nots.

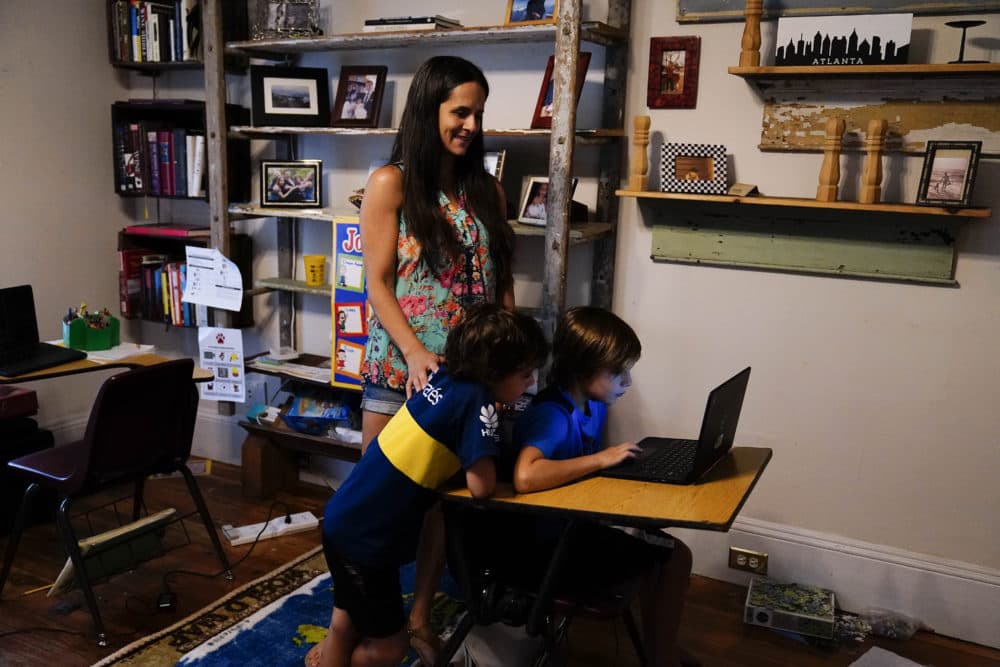

For example, in Chelsea, the high school is unable to lend laptops or tablets, making it difficult for students without computers at home to study and complete coursework. In Chicopee, class sizes are burdensome on teachers and students alike, with as many as 26 children in a kindergarten class. Fall River experiences chronic short-staffing, with a single English Language Learning specialist responsible for the needs of 75 students and children serving as interpreters for parent-teacher meetings.

In January 2020, following the passage of the Student Opportunity Act and the governor’s proposed budget, which would have fully funded the first year of the revolutionary funding bill, the plaintiffs dropped the lawsuit. The families celebrated the promise of the act, which modified the school funding formula to increase funding by $1.5 billion over the next seven years, and the opportunities it presented for students in low-income districts, many of whom are immigrants and children of color, to access a rigorous and high-quality education.

[I]n Chelsea, the high school is unable to lend laptops or tablets, making it difficult for students without computers at home to study and complete coursework.

And then, in March, everything changed.

With state of emergencies declared at the municipal, state and federal level, teachers, parents and superintendents scrambled to bring public education online. In one fell swoop, the pandemic both exposed and widened the gaps caused by years of defunding public schools. In wealthy districts, students already had access to laptops or tablets. They could receive personalized attention in smaller virtual classrooms and complete their coursework online and on-time.

But in cities like Chelsea, where over 60% of students are economically disadvantaged and over 40% are English language learners, where residents are packed together in dense, multigenerational housing, often without reliable internet, and where COVID-19 infection rates are among the highest in the state, remote education has been near-impossible.

Now, although the Commonwealth has agreed to level-fund state education for the coming year, the Student Opportunity Act has been on hold. The gaps between the haves and the have-nots that the landmark funding legislation was intended to address will, in the meantime, only grow wider.

These stark disparities are evident in the list of district reopening models provided to the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education on Aug. 18. Higher-income districts like Concord, Lexington, Newton, Wellesley and Needham plan to offer a hybrid model of education. By contrast, districts like Chelsea, Lowell, Springfield, Holyoke, Worcester and Lawrence — many of which, as outlined in Mussotte, teach children in buildings without air-conditioning, adequate ventilation or sanitary materials — will offer only remote learning, leaving few options for parents of children with disabilities or who cannot access childcare.

The gaps between the haves and the have-nots that the landmark funding legislation was intended to address will ... only grow wider.

In Chelsea, for example, nearly 80% of workers were deemed "essential" under Governor Charlie Baker’s spring order that closed non-essential workplaces to halt the spread of coronavirus, working in industries like health care and food preparation and delivery. If the state or districts are unable to provide help and guidance for those families who cannot be present to supervise remote learning, Chelsea’s public school students are in danger of falling behind.

After years of disinvestment in the public schools teaching, feeding and supporting our most vulnerable students, level funding is simply not enough. Additional state money is critical to providing a high-quality education for the low-income students and students of color whose educational needs have only deepened with COVID-19. The Commonwealth must fulfill its promise to the students and families of Massachusetts, as well as its obligations under the state constitution to “cherish” public education.