Advertisement

Commentary

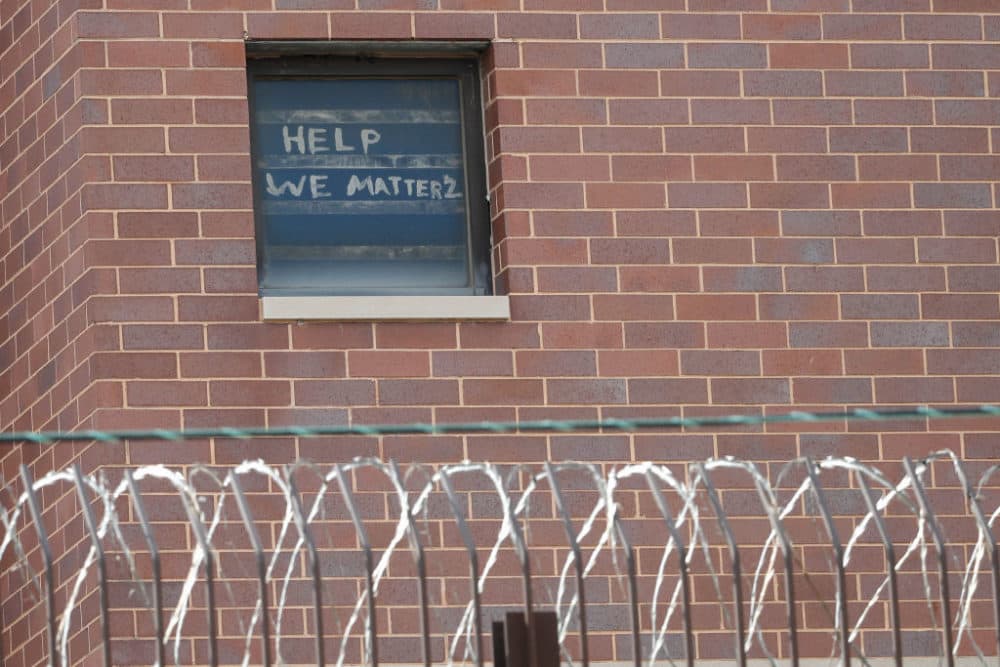

The COVID-19 Outbreak In Mass. Prisons Exposes A Larger Human Rights Crisis

Over the course of one weekend in early November, the number of COVID-19 cases at MCI-Norfolk spiked from 26 to 74. By the end of the week, it had reached 140. The latest available numbers put it at 178.

This past weekend, the state finally began universal coronavirus testing of state prisoners and staff. It may be too little too late.

The Massachusetts Department of Correction's (DOC) failure to properly safeguard incarcerated people from the coronavirus is not simply an isolated act of negligence — it is one facet of a larger, ongoing human rights crisis. The pandemic has simply helped to expose the inhumane living conditions that incarcerated people in Massachusetts regularly face.

The outbreak in MCI-Norfolk was both predictable and preventable. Incarcerated people are among those most severely affected by COVID-19, with an infection rate of five times the national average. In addition, the five largest coronavirus outbreaks in the United States have been in correctional facilities.

Prisons have long been recognized as a petri dish for infectious disease. Severe overcrowding and cramped living quarters make social distancing near impossible in a carceral setting. Lack of access to basic sanitary measures such as hand sanitizer and soap (incarcerated people have to buy these items, and many cannot afford to) have always made prisons a hotbed for disease.

Adding to the conditions inside of prison, the population of incarcerated people are themselves reflective of medical negligence, as mass incarceration disproportionately targets and affects impoverished communities who historically lack access to adequate healthcare.

While COVID-19 has put a spotlight on the issue, lack of basic sanitation is nothing new to those incarcerated at MCI-Norfolk — just ask them about the water. In 2012, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) ordered Norfolk to create a new water supply system, as toxic levels of iron and manganese made the water unsafe.

I have seen the effects of this public health crisis firsthand. In 2018, when I worked at MCI- Norfolk as a substance use counselor, six years after MassDEP’s order, no changes had been made. My clients regularly complained to me of discolored drinking water and showed off rashes caused by showering in contaminated water. Many were even prescribed medication by the prison to combat the water’s painful effects. At MCI-Norfolk, where over 70% of the population is serving 15 years to life, my clients expressed concerns that long-term exposure to the water could create serious health conditions and lead to premature death.

Advertisement

Beyond the physical concerns, the pandemic also exacerbates the damage of incarceration on people’s psychological well being. The DOC uses solitary confinement as a form of punishment, a practice recognized by the United Nations as a form of psychological torture. Due to the recent COVID-19 outbreak, everyone at MCI-Norfolk has been locked in their cells for up to 23 hours per day.

When we believe and perpetuate stereotypes of incarcerated people as second-class citizens, we become complicit in this injustice.

Vital programming, including education classes, substance use treatment and vocational training, which were already understaffed and underfunded, have been put on hold. Two years ago, the DOC suddenly put a limit on the number of visitors people are allowed, despite evidence linking visits to lower rates of recidivism upon release. Now, due to the outbreak, the prison isn’t accepting any visitors at all.

In the wake of the current outbreak, lawmakers and advocates have applied pressure. Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts has filed an emergency motion demanding the release of incarcerated people to home confinement. Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley recently took part in a press conference at the State House imploring Gov. Charlie Baker to take action.

In response to this pressure, the DOC has made some changes, such as expanding client access to phone calls and instituting mandatory testing. However, that it's taken this long for action and accountability is unforgivable.

It is also unsurprising. It is hard to not attribute this lack of protective action, at least in part, to the punitive culture of the DOC. In my time working on the inside, it was not uncommon to hear correctional officers refer to my clients as “worthless” and “garbage.” These dehumanizing viewpoints help to justify abuse and neglect of the incarcerated, and enable the egregious human rights violation and threat to public safety that the DOC is committing.

But the fault cannot be entirely placed on the DOC or Gov. Baker. When the public turns a blind eye to the harm that is being committed, we become a part of the problem. When we believe and perpetuate stereotypes of incarcerated people as second-class citizens, we become complicit in this injustice.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 within the DOC is just one symptom of a much larger disease. It is clear that the DOC has the awareness and ability to stop the abuse and neglect of incarcerated people, and yet it chooses not to. We must hold them accountable to humane living conditions, and compassionate release of incarcerated people immediately, before more people fall ill and suffer.

In the words of a former client of mine, currently incarcerated at Norfolk, “with this knowledge you cannot turn your back. You are responsible for what you do next."