Advertisement

Commentary

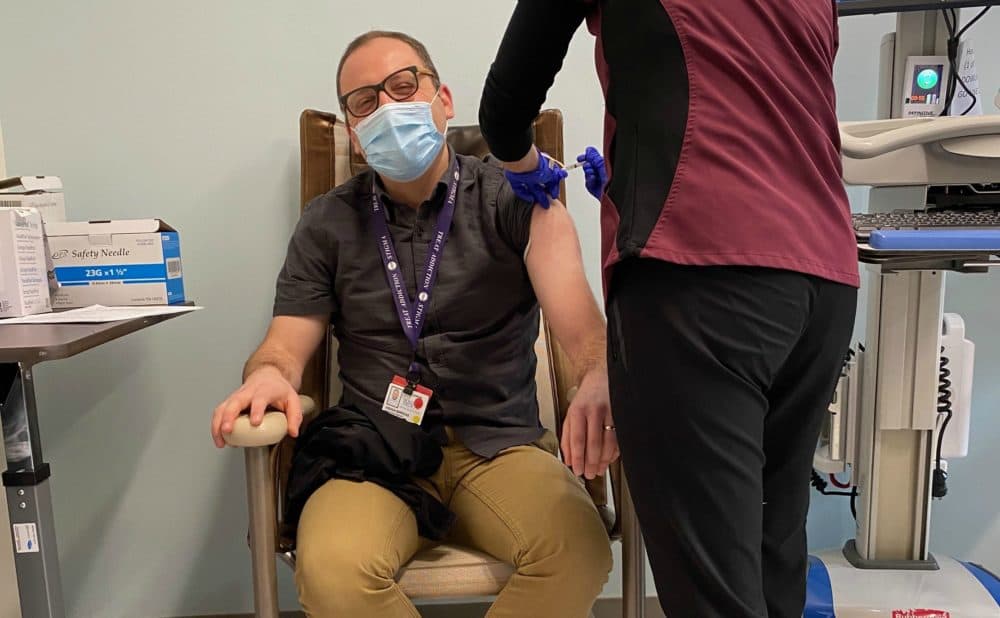

Pulled By Hope And Grief: What It Felt Like To Get The Vaccine

As a child, I didn't like vaccinations. I don't remember this (or I've purged those memories from my consciousness) but my parents are more than happy to remind me of the tears I shed during my visits to the pediatrician. As I grew older, however, vaccinations became more tolerable, more routine. It's been years since I've cried while getting jabbed.

That changed yesterday when I received my first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

As a health care worker, I was scheduled to be in the first phase of the vaccine rollout. I arrived at the clinic in the early morning, checked in, and I took a seat in a high-backed chair next to a table adorned with disinfectant wipes, alcohol pads, sterile gloves and bandages. To my right stood a friendly nurse who asked my name, date of birth and whether I had a history of allergies or allergic reactions to vaccines. Aside from the cameras and crowd of people staring at my bare arm, it was virtually the same process I have gone through for every other vaccination — from influenza to hepatitis B virus.

But as I stared at the small glass vial from which a clear liquid was drawn, I became overwhelmed with emotions and time slowed down. In that moment, I thought of the past 10 months. I thought of Dr. Li Wenliang, the Chinese physician who tried to warn the world of a SARS-like virus and subsequently died from this infection. I thought of the horrible images and reports from Italy and France in February and March, where intensive care units were overwhelmed and ventilators were rationed.

I thought of kissing my wife and children goodbye, knowing I wouldn't see them for days, as I spent long hours helping set up isolation and quarantine sites around Boston. I thought of the abandoned streets of Boston, usually clogged with cars and buses during our 24-hour rush hour. I thought of the frantic calls from family members and friends and people whom I haven’t seen in years, looking for advice or comfort or hope. I thought of the people who have been away from loved ones — unable to embrace in times of happiness and in times of grief.

Advertisement

And I thought of the more than 1,500 Bostonians, 11,000 Massachusetts residents, 300,000 Americans, and 1.6 million people worldwide who have died from this infection — many of whom without family by their side. I thought of my patients. Your families. Our fellow human beings.

And for the first time in a long time, I cried when I received a vaccination.

[T]his was akin to landing a person safely on Jupiter and having them return to Earth to tell the tale.

I cried because I was overwhelmed by grief, but I also cried because of the enormity of the moment. In under a year, scientists developed not just one, but multiple vaccines against a virus that was previously unknown. They used new technology and collaborated across the globe with a single unified vision — defeat the virus. And with the help of brave people who volunteered for clinical trials, they did it. They developed vaccines that are safe and effective and add to our ability to defeat the virus, restore the economy and allow us to return to some semblance of normalcy. This was not just akin to landing a person safely on the moon. Rather, this was akin to landing a person safely on Jupiter and having them return to Earth to tell the tale. It was, for anyone, a moment of many emotions.

So, what are we to do with such a moment in which both grief and hope pull at us? Much like the final miles of a marathon, which are both the most painful and difficult and also the most rewarding and inspiring, we have to push toward the finish line. We have an opportunity to turn our pain and grief into success for humankind.

I am privileged to be among the first to receive the COVID-19 vaccine outside of clinical trials. I do not take this responsibility lightly. I am going to keep working, both to stop the virus from spreading and to eradicate it, despite the pain and discomfort. I will continue to wear my mask and limit my socializing and care for the sick. I hope others — you all, fellow human beings — will join me.