Advertisement

Commentary

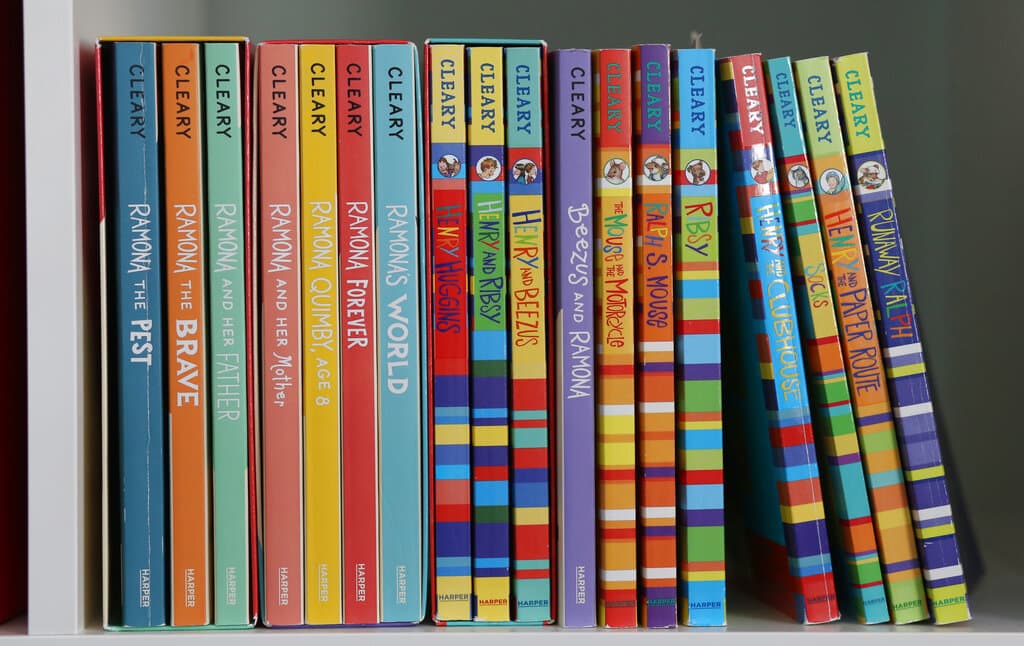

How Beverly Cleary Changed Children’s Literature

I spent the weekend after Beverly Cleary’s death scrolling through social media, reading the numerous testimonials to her from celebrated writers for children. It’s been a week now since she died, just about three weeks shy of 105.

To a person, each author felt she had forged a path for them that made it possible to write about the contemporary world, with all its warts, minutia and dysfunction. (Myself included.) Lynda Mullaly Hunt, author of such books as “One for the Murphys” and “Fish In A Tree,” described Cleary’s influence in a heartfelt online tribute by saying: “I was one of the reluctant readers that she hooked with her rich, true-to-life characters. Her stories were among the first that created mind movies that I now use to create my own novels.”

She advanced storytelling for children, too. For so long the parent characters in middle grade books for children or those for young adults were depicted as either absent or perfect; children were spunky and adventuress, or shy and bookish. With the advent of Cleary’s books, however, authors began to see that — without needing to deliver an overt message — they could write stories in which their characters didn’t fit a particular mold, but could be flawed and wonderfully human. It also became apparent that this emphasis on the portrayal of real life must lead to books featuring children of color by authors of color, who would be encouraged to depict the reality of their own diverse cultures and neighborhoods.

This stress on the real began to pervade young adult novels as well, and, beginning in the ‘60s, many established norms for this genre began to be discarded.

Today we have books such as the National Book Award finalist in 2006, “Rules of Survival” by Nancy Werlin. It’s a powerful story for young adults that deals with the mental illness of a parent. A more recent book, “My Heart and Other Black Holes” by Jasmine Warga, takes us deep into a suicide pact of two teenagers. With "Parrotfish" by Ellen Wittlinger, we fully enter the journey of one who is transgender. My own verse novel, “The Fattening Hut,” which introduces the concept of female circumcision, would not have been possible in the '50s. And when I began writing historical fiction, I found that the best way to make the past relevant was to focus on the smallest details of ordinary living.

I patterned my own first novel for young adults upon Cleary’s Newbury Award winner “Dear Mr. Henshaw,” a middle-grade novel that was different from any of her others. Though on the surface it was a correspondence between sixth-grader Leigh Botts and his favorite author, it was also a writing manual for young readers. I was interested in the epistolary form itself, which seemed to me to be an effective way to tell my tale. It never occurred to me that the dejected feelings of my own protagonist were in any way akin to those of Cleary’s main character, and that she had spent years laying the groundwork, so that I might freely write about my character’s unusual strategy for dealing with a similar sense of worthlessness.

Advertisement

It’s extraordinary to recall that there were only a few distinct children’s book departments in the publishing world when Beverly Cleary was struggling to learn to read, about 100 years ago. Many books for young children back then were imported folk tales, retellings of fairy stories, or were meant for a wider audience. The scant roster of books for 8- to 12-year-olds included “The Bobbsey Twins,” whose protagonists aged from book to book in the 72-book series, “The Hardy Boys,” and the “Nancy Drew” mysteries.

The skill of reading didn’t come easily to Beverly, and the books she was given didn’t take her attention until she happened upon one called “The Dutch Twins” by Lucy Fitch Perkins, an American author, whose story followed 5-year-old fraternal twins as they led their daily lives in Holland in the 19th century. At the time there was no way to know why or how this particular book would change her life, but soon she was frequenting the library in search of books in this series and sleuthing for others about ordinary people.

Ultimately, she became a librarian herself, one who made storytelling on Saturday afternoons an integral part of her job. When a boy once asked why there were so few books written for children about real people, she decided to draw upon her own humorous tales and write some herself.

With the advent of Cleary’s books ... authors began to see ... they could write stories in which their characters didn’t fit a particular mold, but could be flawed and wonderfully human.

Her first book features a boy named Henry Huggins. Like the author herself, Henry has no siblings, but the cast of characters includes his dog, Ribsy, a friend named Beezuz, and eventually her irritating little sister, Ramona, whose name Beverly picked out of the air from an overheard conversation. Little did she imagine that this charmingly unpredictable little girl would so soon rise from bit player to protagonist in a series of 15 books, one every two years.

When a young reader gets lost in these authentic narratives, there is a magic coalescence of understanding without the need of fairy dust, knights in armor, or wizards.

Beverly Cleary would often tell people that her books take place “in childhood” and that she particularly liked to write for third and fourth graders. Though some have compared her to authors of adult literature in her grasp of the human condition, her use of language and talent for satire, I like to think that she was at best uniquely authentic and that the very real worlds she created were, and will remain, as places where 8- to 12-year-old readers can always find themselves.