Advertisement

Covering Climate Now

What The Dustbowl Of The 1930s Can Teach Us About The Origins Of A Looming Megadrought

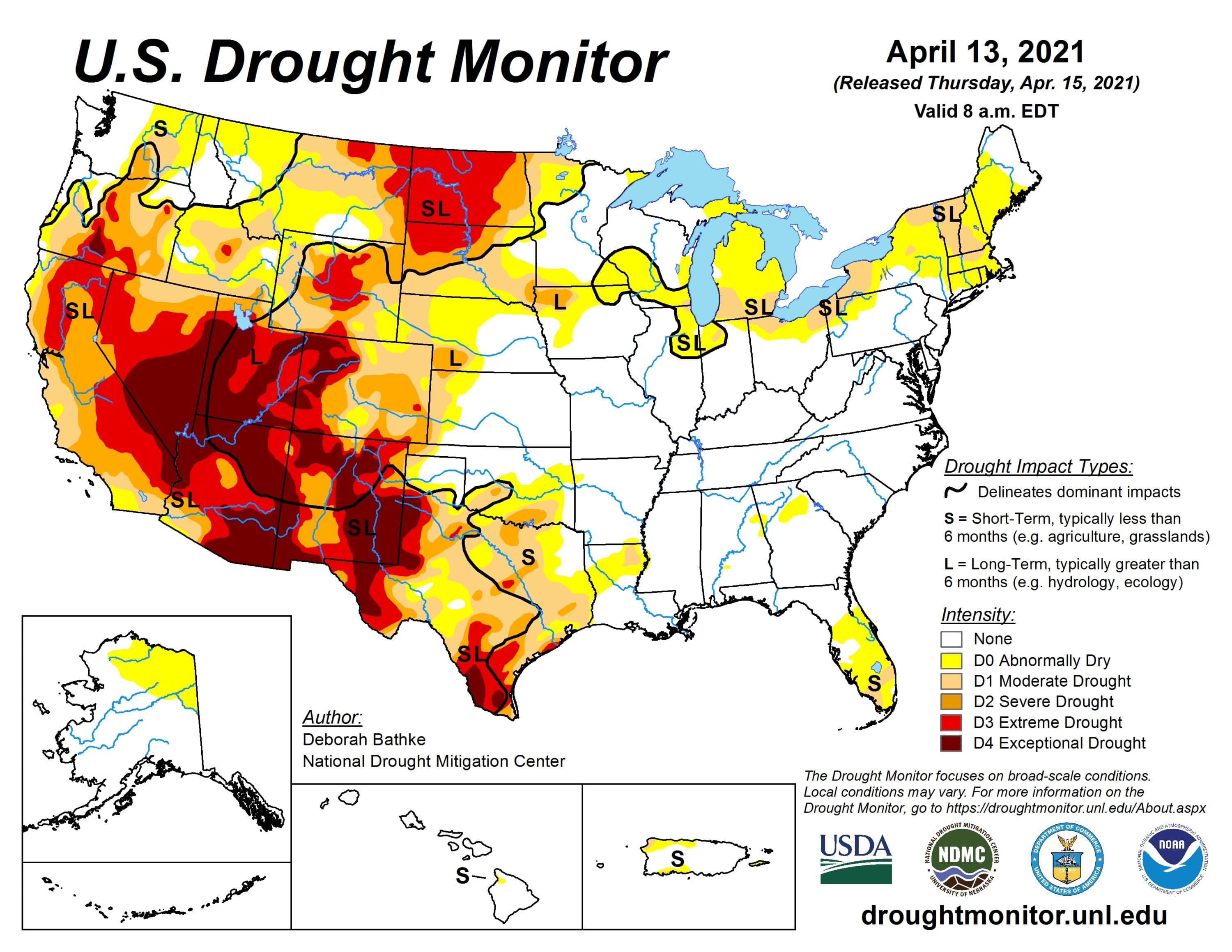

The current drought map for the United States shows a scab-red blotch indicating “exceptional drought” expanding across the southwest quadrant of the country. Because climate change is amplifying the natural drought cycle, the region may be entering a megadrought — a dry period lasting decades — for the first time since the late 1500s.

The epochal drought of the 1930s that led to the Dust Bowl was not a megadrought, nor was it the result of climate change. But the damage it caused was fueled by economic motives and free-market ideologies paralleling those shaping present-day climate policy.

The settlement of the semiarid region centered around the Oklahoma panhandle was the last chapter in America’s westward expansion. Dry conditions throughout the High Plains had beset homesteaders in the latter decades of the 19th century — heat, high winds and dust storms were not uncommon. Cattle grazing had succeeded only sporadically, and settlers were repeatedly frustrated in their attempts to farm.

What changed in the early 20th century, according to environmental historian Donald Worster, was the arrival of aggressive agricultural capitalism.

Despite the well-understood difficulties of dryland farming, there was pressure to introduce agriculture on the southern plains. States needed tax revenue, land speculators sought quick returns, railroads needed freight to ship on newly-laid tracks and businesses in eastern cities were anxious to find new markets.

Land -- even if only marginally suited for agriculture -- was idle capital awaiting a productive purpose.

Congress passed the Enlarged Homestead Act in 1909 to encourage settlement in areas where crop irrigation was infeasible, even while acknowledging the challenges the dry western landscape entailed. Shortly after that, World War I created new demand for American wheat in Europe, where exports from Russia had been cut off.

Technology was pivotal. The Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916 enabled easy credit for farm machinery, and the introduction of gasoline-powered tractors rounded out the capitalist industrialization of wheat agriculture. Worster called it “Henry Fordism” on the plains. Land — even if only marginally suited for agriculture — was idle capital awaiting a productive purpose.

This array of economic forces, aided by an extended period of adequate rainfall, led to “The Great Plow-Up” — the conversion of natural grassland to cropland on an immense scale in the 1920s. When overproduction and the resumption of Russian wheat exports created a surplus that dramatically lowered prices, farmers responded by breaking yet more sod to make up for their loss of income.

The wheat entrepreneur of that era was held up as a social ideal, an independent master of his economic destiny who efficiently extracted wealth from the soil. But this was not Jefferson’s yeoman farmer -- many wheat producers were tenants with no long-term commitment to the land. So-called “suitcase farmers” arrived from the city to plant their fields in the fall, stinting on soil conservation practices that added cost, and then left for the winter. They returned the following summer to harvest their crop and cash out.

Farm prices had already collapsed in the Great Depression when an unyielding drought hit in 1931. Topsoil from millions of acres of failed and abandoned wheat fields was lifted by strong spring winds, creating the dreaded “black blizzards” that buried farms, killed livestock and brought desperate poverty to the region. The “Dirty Thirties” had begun.

By this narrative, the ecological disaster had economic roots. Government policies and fast-buck investors aimed to maximize production and profit without concern for the environmental consequences. The health of the agricultural ecosystem was subordinated to economic imperatives.

Today, an analogous prioritization of advantaged economic sectors continues to hamper the nation's effort to address the climate crisis.

The fossil fuel industry and the federal government have known about the climate effects of carbon emissions since the 1980s. But that knowledge has in no way restrained the pursuit of profits, and the federal government has reliably backed measures to increase oil and gas production.

The same holds in American agriculture, the source of 10% of the nation’s greenhouse gas output. Besides its considerable carbon footprint, industrial farming also has a significant impact on biodiversity loss, nutrient pollution and groundwater depletion. Big Agriculture has made some gestures toward sustainability, but it has often applied pressure on politicians to limit regulation and ensure that profits and production are maximized, just as they were leading into the Dust Bowl.

[A] drought like that of the 1930s is now twice as likely due to climate change.

Environmental costs, including climate impacts, are too often left out of the equation. Ignoring those costs impedes the implementation of strong policy measures and makes it more probable that a warming climate will continue to bring about dry conditions like the West is now experiencing.

New research says that a drought like that of the 1930s is now twice as likely due to climate change. As droughts become megadroughts, the possibility of a new Dust Bowl looms, and modeling suggests its effects would be devastating. Another study published in 2020 reported that rapid cropland expansion is making more of the nation’s topsoil vulnerable to wind erosion — a pattern that echoes the 1920s.

The Biden infrastructure and climate plan would right many wrongs by putting ecology and economy in balance. Without bold action on climate and energy policy, the decade of the “Dirty Thirties” in the 20th century may pale in comparison to that in the 21st.

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration of more than 400 news outlets committed to better coverage of the climate crisis. This year's theme is "living through the climate crisis."