Advertisement

Commentary

'Late, But Not Too Late': What Biden's Recognition Of The Armenian Genocide Means To My Family

When President Joe Biden formally recognized the Armenian genocide last Saturday I was one of millions of Armenian-Americans feeling both grateful and sad.

I felt grateful that my country had finally acknowledged a truth well-established by historians: that 100 years ago the Ottoman Empire — the Turks — killed 1.5 million Armenians living in their midst as a Christian minority. This nearly-successful effort to wipe a people off the face of the earth inspired a human-rights lawyer to coin the word “genocide.”

And sad because the people who most needed, who most deserved, to hear their president officially say the words no U.S. president ever had – “Armenian genocide”-- were, to a person, long dead. There is not one known survivor to the Armenian genocide alive today.

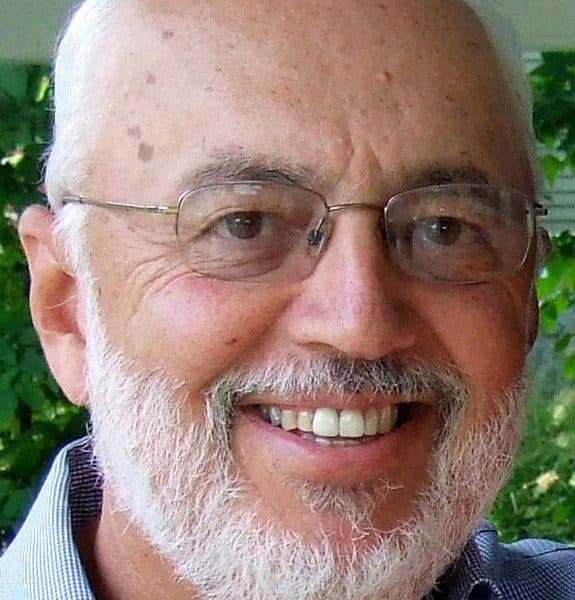

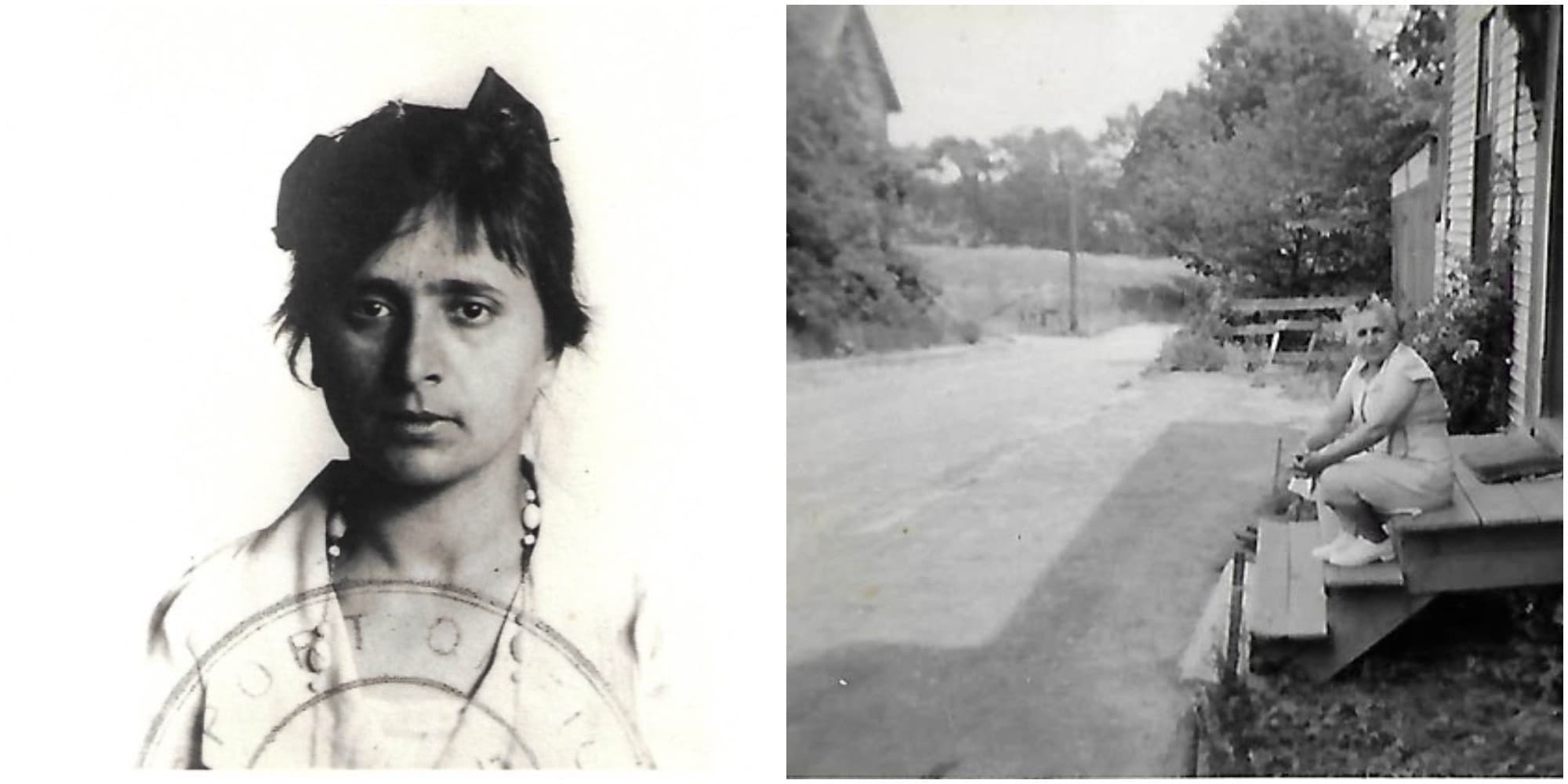

Among those long in their graves is a woman named Gulenia Hovsepian Banaian: Rose to her friends; Nana to me.

My Nana’s father was murdered in the Adana Massacre of 1909, a precursor to the full-blown genocide of 1915 to 1918. Her mother died in 1918, likely of starvation on one of the forced marches across a desert to a concentration camp. Her baby brother, my great uncle Moses, also died of starvation.

Nana and her siblings escaped from their village in the Musa Dagh region, set in the mountains a few miles from the Mediterranean Sea. She was raised in a Lutheran orphanage in Beirut, later worked as a nurse’s aide in Cairo and then came to the United States for an arranged marriage to an Armenian man who had settled in Dover, New Hampshire.

My grandparents, Gulenia and John Banaian, had six children including my mother. Months after their youngest child was born, my grandfather died and Nana took a job in a cotton mill. She raised her family in the tenement that my grandfather had bought with his meager savings from working in Dover’s tannery. My family lived in the tenement next door. She was a warm, loving woman who gave iron-armed hug and fed me meals when my parents were at their factory jobs.

Like most children and grandchildren of immigrants, I was raised to be more American than ethnic — not that the Armenian side was hidden or a source of shame. We ate the foods of her homeland: stuffed grape leaves, pilaf, shish kabob. I knew she was a survivor of the genocide, but there were never any details, just Nana’s sad, deep, dark watery eyes to suggest something she had not forgotten.

Advertisement

For decades, I knew little of her story, until I discovered a recording she had made of what happened when she was a 9-year-old girl.

In that recording, she recalls a spring day in 1909 when her family had sent her to gather their cows so they could be taken to pasture. That’s when a Turkish boy ran up to her and shouted, “They’re killing the kifir.” Translation: they’re killing infidels, the Christians, the Armenians.

The Adana Massacre had begun a few days earlier, 150 miles away. Her father grabbed his rifle and sabre and ran towards the village center to join other Armenians to defend their families. But, as Nana recalls in the recording, “There were too many of them. He tried, he did … All I’ll say is, hundreds of them. He was killed. He was beaten."

His body was found not far from their home, stripped of everything but his homespun shirt.

Historians estimate that from 15,000 to 25,000 Armenians were killed. It was one of the many pogroms that were preludes to the genocide, where the atrocities shocked the world. Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. ambassador to Turkey at the time of the genocide, called the treatment of Armenians by the Ottomans “sadistic.”

Armenian mothers killed their children rather than see soldiers cut their heads off. Families were marched off high cliffs. Women were raped within earshot of their husbands, who were then executed. Tens of thousands died on the forced marches for lack of food and water or were shot or stabbed if they fell behind. Wells were found stuffed with dead Armenians. Others were nailed to a cross.

These are the memories, the truths, that haunted Armenians like my Nana. Their pain was deepened by a lifetime of waiting in vain for the world to officially acknowledge what happened to them was more than a series of massacres, more than mass murders. It was a genocide: the killing of a people.

These are the memories, the truths, that haunted Armenians like my Nana.

Thirty years ago, my nana was asked about Turkey’s denial of what was done to the Armenians – a denial that continues to this day. Biden’s announcement made me recall her words: “It happened,” she said, in a rare defiant tone. “My father went. My brother starved to death … my mother died on the road.”

This weekend I drove to Pine Hill Cemetery in Dover and stood at Nana’s gravestone. She died in 1995 at 96 years old, at a time when the efforts for the U.S. to acknowledge the genocide were beginning, but thwarted time and again for fear of offending Turkey, a key ally.

As I stood there, I wondered what she would think of Biden’s announcement. I settled on: “Late, but not too late. We survivors of the survivors, can take some comfort in the name of our fathers, mothers, grandparents.”

Leaving the gravesite, I noticed I had received a text, not from the grave, but from the San Fernando Valley, home to thousands of Armenians, including Nana’s youngest daughter, my Aunt Lity.

Her few words were the next-best thing to a message from the hereafter: “Biden said Genocide!"