Advertisement

Commentary

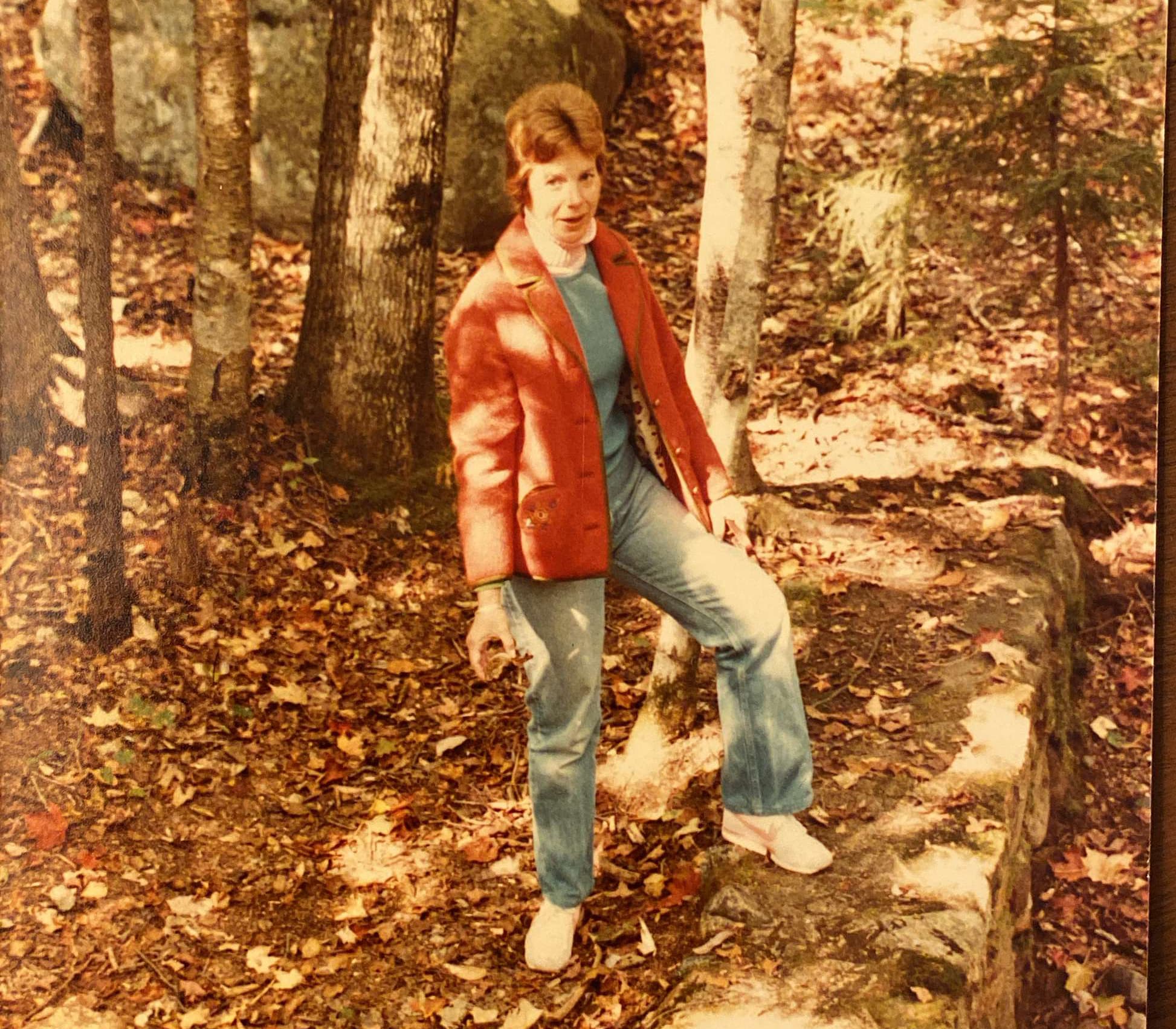

Remembering My Mom By Restoring Her Coat

When I was in college, my mother gave me a burnt orange, boiled wool jacket with flowers embroidered on the pockets. The coat had been hers in the ‘60s, but there was no sign of wear on the garment when she passed it on to me decades later.

My mom was impeccable in her care for things and people. I loved that coat right through its lining. Then, when the jacket was less sturdy, I returned it to her, wilting, on a bent hanger. She might have criticized me, but she didn’t. Instead, she gently suggested that coats can be relined.

In February, my mother sustained a catastrophic brain injury after falling from her back steps. Her death was sudden. Because of the pandemic, I had not been inside her house for 11 months. The day she died, I moved slowly through every quiet room.

A fiber artist, she had cabinets filled with fabrics collected for projects both completed and still in the imagination phase. I’d open and shut the cabinet doors, pained to give the cloth away, overwhelmed by the idea of keeping it. After she died, every print and color seemed to contain her very essence.

Insert Marianne Hatton, a renowned quilter and one of my mother’s oldest friends. Wearing masks, we sat on the floor of my mom’s sewing room, cataloguing her inventory. Mom’s books joined the permanent collection at the New England Quilt Museum and found their way into the hands of Marianne’s students. A friend who my mom taught to knit is using her needles to create hats for premature babies.

The Massachusetts Chapter of the American Needlepoint Guild gladly accepted embroidery supplies and periodicals for their members and extended my mother’s reach by sharing her stash with a group of young 4-H sewers. Even in her death, my mother has helped to plant seeds that will sprout the next generation of fiber artists.

As I write this story, volunteers are sewing my mother’s fabric into quilts that will be auctioned to benefit women in transition, babies born to incarcerated mothers and families facing food insecurity. And on my mother’s Bernina machine, Marianne is sewing twin quilts for my sister and me. Fabrics can talk. I can hear my mother’s whisper, “I am still with you.”

Advertisement

For my mother, recovery was not possible. I needed to secure a second chance for the boiled wool coat.

Mireni, a fourth-generation couture whose mother taught her how to sew, owns a tailor shop in Concord, Mass. When I stopped by her studio just after my mom died, she shared that her own mother is battling cancer in Brazil. The pandemic means they cannot be together. I was not self-conscious when I wept with Mireni, relaying my mom’s shocking death and my desire to have her jacket relined. Mireni knows what it means to miss a mother.

My coat and I were in compassionate, expert hands. Together, Mireni and I looked at fabrics from my mom’s collection. I could not settle on just one pattern, so we chose several for the job. She would construct panels with which to line the coat, a quilt of sorts, sewn from favorites and hidden beneath the orange shell.

Had my mother met Mireni, she would have found a fellow creator and generous soul. Further, her perspective on silver linings would change.

How did Mireni know to salvage and launder some of the coat’s original lining, to embellish the sleeves with secret custom cuffs? The torn cloth that had languished in the coat for years has been artfully replaced with my mother’s beautiful material.

“No charge,” Mireni said to me, plucking the slip from the hanger when she saw me reach for my wallet.

“I insist,” I said. COVID has crippled small businesses, especially ones that rely on people who wear dry cleaned clothes. Her craftsmanship is exquisite, the stitches an original love poem. She shook her head and held up her hand. Mireni understood why the coat needed to be fixed and told me she was honored to help.

“For our mothers,” she said simply.

Although my mother is dead, she remains a talented fiber artist, her spirit knitting people together. She constructed the Zoom quilt of squares during her online memorial service and lives on in the work other artisans will create using her books, supplies and fabrics.

Growing up, my mother told me to be alert for silver linings and to celebrate kindness. Had my mother met Mireni, she would have found a fellow creator and generous soul. Further, her perspective on silver linings would change.

Mireni has shown me, as her own mom taught her, that textured, variegated and repurposed linings can make us feel just as grateful.