Advertisement

Commentary

My Mother Was More Than Either Of Us Knew

Washing the dishes the other day, I picked up the white enamel colander I’d used to drain thawed berries before folding them into cake batter. Dishwashing is a thoughtless habit, but this time I found myself considering the colander with its arcing rows of holes, black rim and dark, chipped places. It has been in my life forever.

My mother bought it when we lived in Oregon — before we moved back east 60 years ago. She likely found it in a five and dime store. And here it is still, ready for each day’s rinsing and draining.

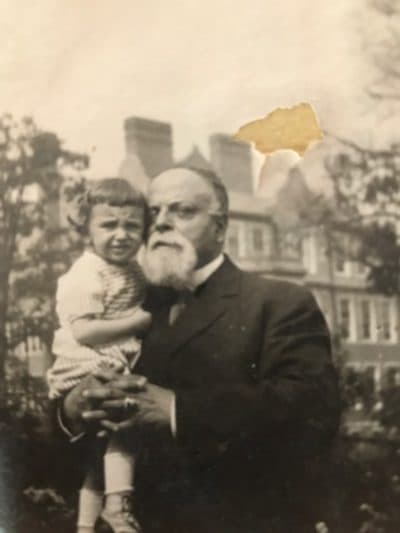

My mother’s parents came from Naples, Italy to New York at different times. Their marriage soon ended, though I’m not sure why. My mom grew up in a house with her mother, grandmother, two uncles (for a while), and, until he died when she was 7, her beloved grandfather, a professor.

Even though she did well in school – and, in 1939, was the first woman in her family to graduate from college — losses, tensions, turmoil and the confusion of assimilating in an era when Italian-Americans were scorned, took their toll, leaving her chronically unsure of herself. She once let slip her great distress when, as a girl, her mother made her to walk to her father’s house to try somehow to extract the child support he owed. That sense of shortfall about her own worth lingered.

As an adult, the kitchen became my mother’s one certain domain. She doubted every other talent she possessed; but every day, in the late afternoon, she’d tie on an apron and set to her task, content to work alone rinsing, chopping, sautéing. Her hands and fingers were delicate, at ease with her labors. Even years after her death in 2007, people who’d eaten at our table spontaneously recalled the unusual pleasure of her meals. I relished them too; and now, looking back, realize she mapped for me a queendom of culinary joy.

My mother, Anna “Ann” deChiara, had grown up watching her grandmother and mother cook, sometimes elaborately (at least once they prepared a classic French galantine for New Year’s Eve guests) but often simply the dishes they knew from Southern Italy.

Eventually my mother, too, would stew escarole with raisins and garlic; simmer tomato sauce; stuff and bake artichokes, or, for a special occasion, a stuffed veal roll, scattering bits of ham, cheese, hard boiled egg and peas onto a flattened piece of veal, roll it up, tie it with string and braise it. Often toward the end of summer she’d roast ripe tomatoes, first cutting them in half, squeezing out the seeds and carefully filling each piece with bits of anchovy, garlic, capers, basil, black olives, pignolias, then sprinkling breadcrumbs and olive oil over them, and baking them in a hot oven until they collapsed in on themselves shrunken, caramelized, slightly blackened and intensely flavor-filled.

Advertisement

She enjoyed the occasional cookbook and kept a recipe box, but mostly she sensed what would taste right. She preferred to be alone in the kitchen, and used its shelter to untangle whatever the day had delivered that felt fraught. But I interrupted her with chatter, watched and sampled, and gradually absorbed her flavors deeply. Later, I taught myself how to recreate them.

When my parents moved to Oregon in 1949, it was still sparsely settled. In those years, having to stretch each dollar, she shopped thriftily in grocery stores and summer farm stands.

When my grandmother visited, we’d walk to vacant lots to gather dandelion greens and wild mustard that they’d soak and wash, then braise with olive oil. In summer, we’d fill paper bags from a neighbor’s apricot or cherry tree. We had a pear tree in our backyard, and a walnut tree whose ripe fruits we harvested and shared. Some seasons, my mother put pickles in canning jars and made jam from local strawberries, then dotted cookies with the jam.

Though love bound us, my mother and I were rarely easy with each other. Happier at a distance, she distrusted family closeness, and lacked the patience to instruct. It would have been unbearable to her to try to teach me cooking, or anything she knew. Maternal intimacy often confounded her. She didn’t want me to be like her and said repeatedly that I was my father’s girl. Perhaps, fatherless herself, she construed the hand off as a gift. I didn’t object.

I pleased her by pretending to an independence I did not possess, often following behind her, unnoticed, through the streets of her passions; learning by watching.

Though my ability is nil, I now take an Italian lesson every week, still sometimes hearing her easy cadence in my head. She was a lover of newspapers, books, art, classical music, travel, gardening. She was honest, generous, curious about the world, eagerly sociable with friends. She laughed readily, enjoyed chewing over political news or gossip, the pros and cons of a writer’s latest book (or latest mistress), the dimensions of a singer’s voice. Because she devalued herself so constantly, I have only gradually understood my good fortune, how many of my most treasured ways of being come from her.

Now, as time has eroded pretense, my indebtedness for what she offered and what I took, stands out plainly, as demarcated as stone walls on a mowed hillside.

Indeed, if I could rewind hours, reverse water that’s long since flowed through some cosmic sieve, I’d like to reckon with what I owe: take her hands, find her eyes, dismiss her demurring reticence, and tell her gently about the recollections that white colander summoned. How she possessed and gave so much more than either one of us allowed herself to know.