Advertisement

Commentary

I'm A Black, Gay Physician. I'm Here Today Because My Friends Saw Me — All Of Me

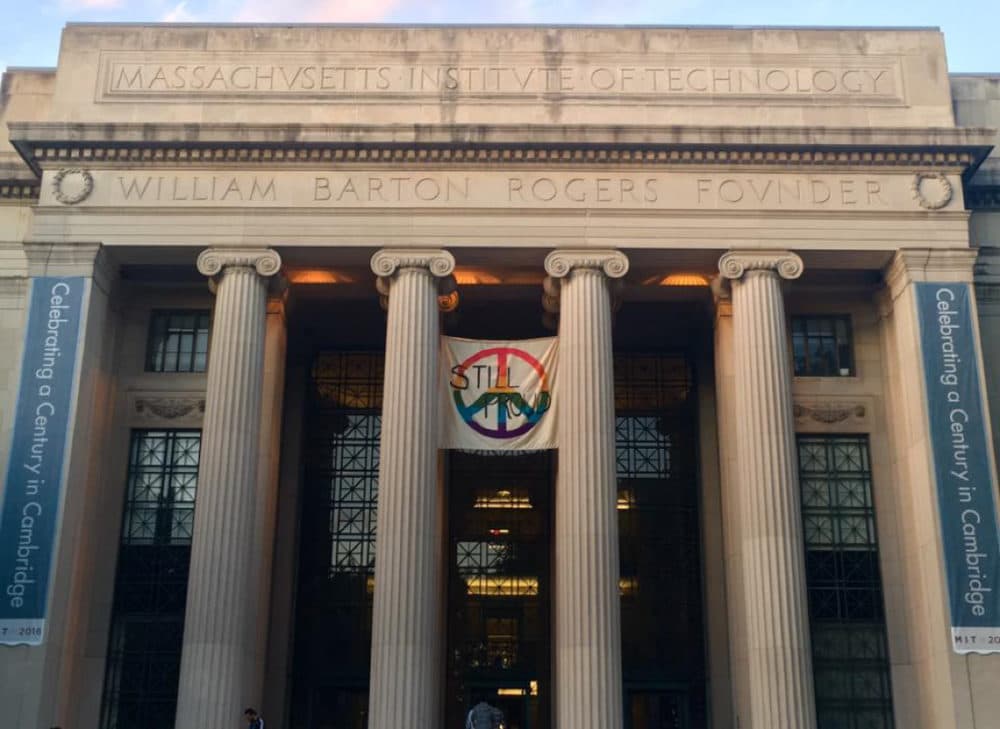

On my phone's lock screen is a photo I draw strength from daily. On the steps of the pantheonic building where I attended college and graduate school, I stand with over a dozen close friends. Our hands intertwine; our arms fondly encircle each other’s shoulders. We wear the button-up shirts and dresses of college grads, but on our heads, each one of us sports a tiara.

We stand as chosen family, one month before I leave Massachusetts to start medical school in Chicago. I don’t know it then, but what I learned from them will save my life in the years to come.

These friends validated my identity and helped me unshackle the self I’d been hiding, or had been forced to hide. They taught me that being African-American and gay were beautiful aspects of my entire self, and that I was so much more than I ever dreamed possible.

Seven years later, I’m now a pediatric psychiatrist. I’m trained in the science and the literature. But, through this chosen village, I also understand how the power of community can heal.

There are statistics about how a sense of connection is essential for minoritized individuals. In 2015, 4.5 times as many LGB-identified high school students attempted suicide compared to non-LGB students. Forty percent of transgender individuals report having made a suicide attempt. Black children are dying by suicide at increasing rates as they face a rise in the number of hate crimes in America. In the Asian American community, anxiety and depression have spiked due to racism during the coronavirus pandemic. For minoritized people, a lack of community and support can be lethal.

I experienced how a life could change when people stood for you and with you.

The statistics for the power of community to save lives are just as impactful. The Trevor Project noted that “LGBTQ youth having at least one accepting adult were 40% less likely to report a suicide attempt in the past year.” Using a transgender individual’s chosen name can decrease suicidal behavior by 56%, and suicidal ideation by 29%. Connectedness between individuals increases their ability to cope during times of stress and when facing adversity, as does someone feeling connected to their university or community organizations.

Validating someone’s existence can save their life. But those are numbers on a page. How do the statistics play out in real time?

When a friend told someone to stop pejoratively mimicking my hand motions — and that person did — I began to feel as though I mattered. Parts of myself I had shut away because of fear flourished when another friend laced my eyes with eyeliner and gold eyeshadow before a fraternity party, a party where brothers in the fraternity remarked on how pretty the makeup looked. A friend sharing that she also suffered from depression let me know I wasn’t alone.

My fragmented heart healed when friends validated my experiences around discrimination. Being part of a campus where we celebrated our diversity of religion, sexual orientation, gender, race, and so many other facets of identity rebuilt my soul in ways I’d once only dreamed could happen.

My friends saw me. Their companionship showed me how what the world too often says about the minoritized is wrong in every way. Each one of them, without hesitation, reached out a hand and intuitively taught me how to sit in the chaos in which I was drowning. I experienced how a life could change when people stood for you, and with you.

When I released my internal shields crafted to protect myself, I had the distinct pleasure of seeing others do the same. Knowledge of my educational, economic and other privileges led to my leveraging those advantages for others. I became the person I always wanted to become: a unicorn-phoenix who did anything and everything I could to help those around me feel seen, loved, and that much more able to let themselves dream.

Everything during those six years wasn’t perfect. I was rejected from a fraternity when I first arrived at college, because I was gay. I was many people’s first openly gay friend, which came with necessary conversations around bias, and I had to have discussions around why people shouldn’t use the N-word.

In this photo, too, I have no idea that I’m about to be crushed during medical school. I’ll lose my hard-won voice. At the end of those four years, I’ll race back to my friends in Boston for psychiatry residency, but, even then, too many days will be a never-ending cycle of damaging microaggressions and overt aggressions which fracture my sense of self and force me to work through a speedy recovery to prepare for each new day.

While I’ll struggle, sometimes deeply, with depression and suicidal thoughts during both medical school and residency — including two moments of true crisis — memories and moments with those who truly saw me will safeguard me from becoming the one statistic I wouldn’t be able to come back from.

These friends validated my identity and helped me unshackle the self I’d been hiding or had been forced to hide.

What I learned from my chosen family about leading with my heart will help me maintain enough of my sense of self to survive — enough, even, to learn to thrive. Their presence will create a safe sphere outside of work that will allow me to tackle issues around diversity and to create a similar safe sphere inside work. Honest conversations with them and others will help me see through the gaslighting I and so many others experience, teach me to find true allies and avoid false ones, and even remind me how to feel joy as changes begin to occur.

Seven years later will find me in San Francisco as I train to be a child and adolescent psychiatrist. My depression is in remission for the third time in my life, and I feel safe in a way I haven’t since posing for this photo. Not only am I lucky enough to be working with kids around their mental health struggles and coming to terms with their identity, but I’m also writing about minority stress and collaborating with others to hopefully reach those who need to know, like I did, that they are never alone.

Though many of us are separated by distance now, we constantly stay in touch. We’ve had weddings, vacations, triumphs, losses, deaths in our families, successes in finding our place in the world, and, most recently, a baby shower over Zoom. We may never gather on those steps again, but I will never forget how they shared pieces of their hearts with a young man who didn’t know if he would ever find true acceptance.

I would not be where I am now without the people in that photo who first saw me for who I truly am. Because of them, with them, for them, I will always be a young man who was once upon a time — and still is — fondly nicknamed Dream.