Advertisement

Commentary

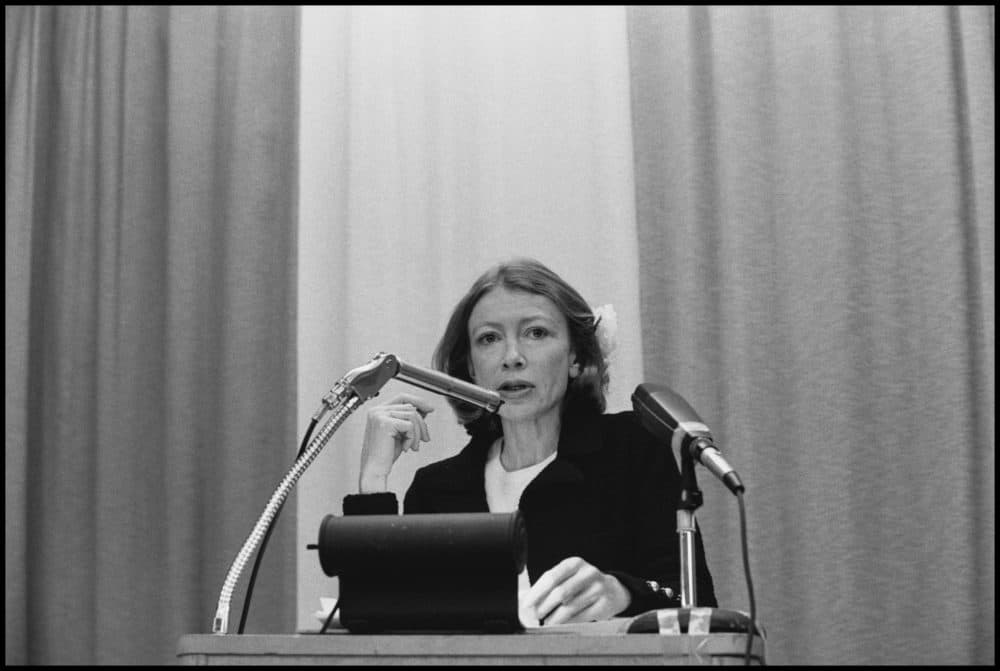

The ruthlessness of Joan Didion

There has been and will continue to be remarkable similarity in the tributes written to essayist, novelist, and screenplay writer, Joan Didion. That’s because her voice was so distinctive — so mordant and savage and bleak — that once heard, it could not be unheard or described with sunnier adjectives.

Even as I write just the two tentative sentences above, I find myself starting to fall into her rhythms and tone. “Sunnier adjectives” is Didionesque, a deceptively straightforward description that nonetheless needles, that leaves you to wonder if it carries some intrinsic and jagged irony that could explain the discomfort you suddenly feel.

Writing in the second person as I just did, repeating a word or a phrase as I just did — these were just two of Didion’s literary tics. Used by lesser authors, they could quickly become tiresome. But for Joan Didion, pioneer of the “new journalism” in which writers incorporated literary (as opposed to purely reportorial) techniques and were unabashed participants in the stories they were telling, voice was inseparable from subject.

The subjects she took on were wildly varied, reflecting a curiosity that only seems to have been dispassionate. She came to prominence writing about cultural icons like Huey Newton and Howard Hughes, pursued her very Californian interests in the Reagans’ overhaul of the Governor’s Mansion in Sacramento, the design of shopping malls, and the source of the water pouring from the taps of Angelenos, and made political forays into the lives of El Salvadorian peasants and Cuban emigres, the predictability of Bill Clinton’s impeachment, and the wrongful conviction of the Central Park Five.

But the voice was always the same. Joan Didion chronicled what was being lost, even while acknowledging that she was grieving for something that may not ever have existed.

This was perhaps most apparent in her writing about her home state of California, which she once described as “a hologram that dematerializes as I drive through it.”

Joan Didion chronicled what was being lost, even while acknowledging that she was grieving for something that may not ever have existed.

Didion herself seemed to relish making the unpopular statement. She was an unclassifiable political malcontent. Her scorn for the New Left of the late 1960s was palpable. (“This sense that the world can be reinvented smells of the Sixties in this country,” she wrote in an essay about the anti-war, iconoclastic Bishop James Pike, “those years when no one at all seemed to have any memory or mooring…”)

But it was matched by her contempt for country club Republicans and Middle American believers who managed to simultaneously hold a faith in relentless progress and a devotion to the status quo.

“Here were some people who had been led to believe that the future was always a rational extension of the past … Of course, they would not admit their inchoate fears that the world was not that way anymore,” she wrote upon attending a conference of the Jaycees in 1968. “… It occurred to me finally that I was listening to a true underground, to the voice of all those who have felt themselves not merely shocked but personally betrayed by recent history. It was supposed to have been their time. It was not.”

Advertisement

Like many students of creative nonfiction, I worshipped her for a time. Joan Didion was a name-dropper but not a gossip, a critic but not an advocate. She was a stylist with substance to match; a unique voice recognizable in a single sentence. Almost every essay offered a master class in craft. Didion repeated phrases not to assuage disquiet, but to escalate it. She made lists to illustrate how naming and itemizing is a feeble palliative for chaos. Describing how prepared and well-equipped she was for travel during those years, she notes that the one item she lacked was a watch:

"In other words I had skirts, jerseys, leotards, pullover sweater, shoes, stockings, bra, nightgown, robe, slippers, cigarettes, bourbon, shampoo, toothbrush and paste, Basis soap, razor, deodorant, aspirin, prescriptions, Tampax, face cream, powder, baby oil, mohair throw, typewriter, legal pads, pens, files and a house key, but I didn’t know what time it was."

And my God, what courage she had! Uneasy, unaligned, and unafraid, Didion treated every aspect of her life as material. She quoted her own psychiatric records to illustrate the profound disorientation she herself experienced during the Sixties (and clearly not just then), writing, “By way of comment I offer only that an attack of vertigo and nausea does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968.” She wrote a book about her husband’s death, another about the death of her daughter. In reading the latter, a slender volume called "Blue Nights," it seemed to me that her literary techniques, once as sharp and sure as arrows had lost their edge, become as worn and aimless as the author herself. But not the self-awareness that gives any personal essay its power. That blazed on.

“My only advantage as a reporter is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests,” she once explained. “And it always does. That is one last thing to remember: writers are always selling somebody out.”

And there it was, the ruthlessness that made her a singular chronicler of her culture.

There’s an electrifying moment in "The Center Will Not Hold," a documentary about Didion made by her nephew, Griffin Dunne, in which she reveals the frigid curiosity that made her so unique. She is describing a scene that she wrote about in "Slouching Towards Bethlehem," an episode in which she visits a Haight-Ashbury home and meets a 5-year-old girl in white lipstick, sitting on the floor, leafing through the comic book her mother has given her along with a tab of LSD. When she got to that awful punchline, I was horrified. What kind of a mother does that?

But then Didion says this to her nephew: “Let me tell you, it was gold. You live for moments like that, if you’re doing a piece. Good or bad.”

And there it was, the ruthlessness that made her a singular chronicler of her culture.

As deeply as I admire much of her work, I no longer choose to emulate it. I don’t want to be a great writer at any price. But now, reading of her death, I’m reminded of an essay she wrote about the Hoover dam, one that contains a picture of how I hope to remember her.

“…That was the image I had seen always, seen it without quite realizing what I saw, a dynamo finally free of man, splendid at last in its absolute isolation, transmitting power and releasing water to a world where no one is.”