Advertisement

Commentary

What I learned in middle school is the lesson all of us need right now

When I was in eighth grade, in the late 1960s, I was called a k--- by a group of Italian and Irish girls in my junior high school in Newton, Massachusetts. This group smoked cigarettes just off school property in an area we called “the wall,” which I had to walk past every day on my way home. The wall functioned as a long stone bench for about a dozen kids. One afternoon, after school let out, some of the girls threw lit cigarettes at me and a few of my Jewish girlfriends. One of the cigarettes burned a hole in my jacket.

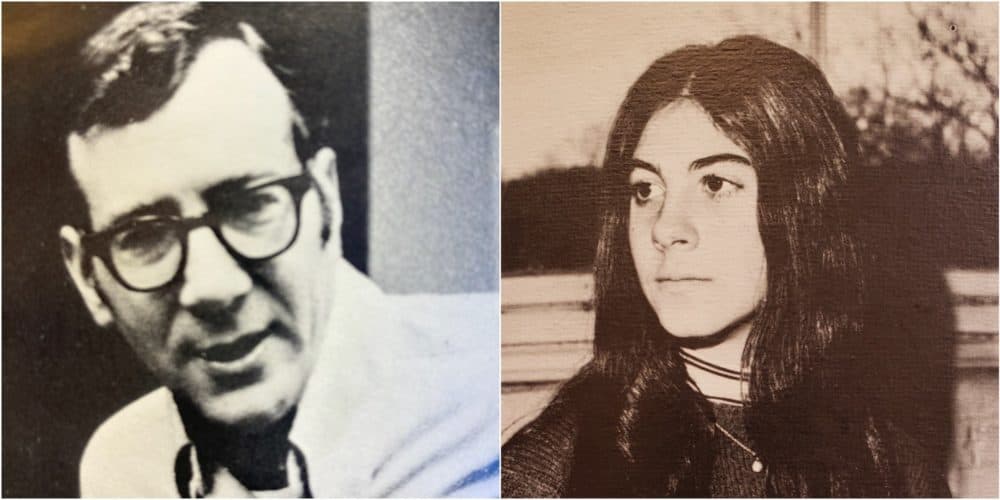

Scared and harassed, I didn’t know what to do. The next day, I decided to talk to my social studies teacher, Mr. Kunitz. I liked how he had treated me earlier in the semester. When I had spoken out of turn in his class, rather than admonishing me for not raising my hand, he stopped what he was doing, looked at me with curiosity and a bit of mischief, and invited me to come up to the podium and express my opinion. While I can’t remember what I said that day, I do remember looking out at my peers — about 25 of them — feeling empowered, a word I didn’t use back then.

I told Mr. Kunitz what had happened at the wall, and he suggested I invite the kids who had been harassing me to meet with me and some of my friends. He would moderate at a neutral location, which turned out to be his house, a few blocks from school. I said OK, and made a list of about 10 girls from the prevailing Irish, Italian and Jewish middle school cliques.

In Mr. Kunitz’s living room, we sat cross-legged on the floor. He opened the meeting by calmly laying out the ground rules: be respectful, give everyone a chance to speak. Then he turned the meeting over to us.

After an awkward silence, someone said, “What do you do on the weekends?” That simple question opened the floodgates of our common denominators. We discovered that we all liked similar things: going to movies, hanging out with friends, sleepovers, sports and music. Much to our collective surprise, we wanted to meet again.

The second time, we gathered in the basement of my house. Mr. Kunitz sat in a chair, away from the group. He never had to moderate. I think we met once more at the home of one of the girls who smoked at the wall. After that, we abandoned the formal construct of meetings with Mr. Kunitz. We gathered on the playground at lunch. We mingled at school dances and sports events and began visiting each other’s homes.

Something special was happening. We stopped harboring fears and clichés and reductive labeling of cultures. Instead, we threw open our inner doors and released ourselves into the glorious wild landscape of open air and space where we all stood taller and galloped freely in celebration of our differences. It became cool to like each other. We became friends.

I was thinking about this incident because of volunteer work I had been doing at my former job at a Boston hospital. As part of a diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) committee, we initiated a volunteer email chain for 130 staff to share personal stories of DEI challenges or inspirations. This motivated me to contact Mr. Kunitz, who I now call Dan. I had seen him periodically over the years. He came to several of my book launches in Brookline, but I hadn’t talked to him about the incident at the wall in years. During our recent lunch, he asked if I had stayed in touch with any of those kids. Mostly, I had not. So, I got on the phone and on Facebook and learned a few things that surprised me.

Advertisement

Several Jewish men who were classmates from that time wrote to tell me they had had no idea those meetings had occurred. They recalled suffering bullying in silence or with fist fights. One of my close girlfriends reminded me on the phone how deeply hurt she had felt and still feels because I had not included her name on that special list of invitees. My girlfriend had tragically lost her mother the year before and my excluding her from those meetings felt doubly unforgivable and heartless.

These discoveries brought up all sorts of questions. Exclusion is heartless. Why do we do it? What power do we gain and simultaneously lose when we exile a friend or an entire group? How do these closed circles manifest in our schools and employment settings? Who is teaching children and adults how to talk constructively about discomfort? Today, America’s extreme political divisions are no more evolved than the immature behaviors of junior high cliques. It’s even worse, because these divisions are driven and nurtured by adults.

America’s extreme political divisions are no more evolved than the immature behaviors of junior high cliques.

After my recent lunch with Dan, I thought: wouldn’t it be amazing if we could somehow replicate a Mr. Kunitz in every state and school district, and take his inclusive approach even further to solving these problems of bias and banishment? Dan Kunitz’s teaching method of inclusion is critical to our country’s resilience and ability to repair. The banning books and banning people in our current environment is causing America’s foundation to weaken and cave into itself.

Curiously, I don’t remember talking about the cigarette incident at those three meetings with Mr. Kunitz. What I do remember is the thrill of connecting; the feeling of strength and safety it gave me. And I think that is exactly what Mr. Kunitz’s genius as a teacher engendered. He didn’t focus on blame. He wasn’t interested in pointing fingers. He didn’t fan the flames of “us” versus “them.” He taught us how to celebrate our differences, and in this way, we felt heard and seen and embraced as individuals and as a group. Instead of deepening our divides, he helped us build a bridge.