Advertisement

5 Questions

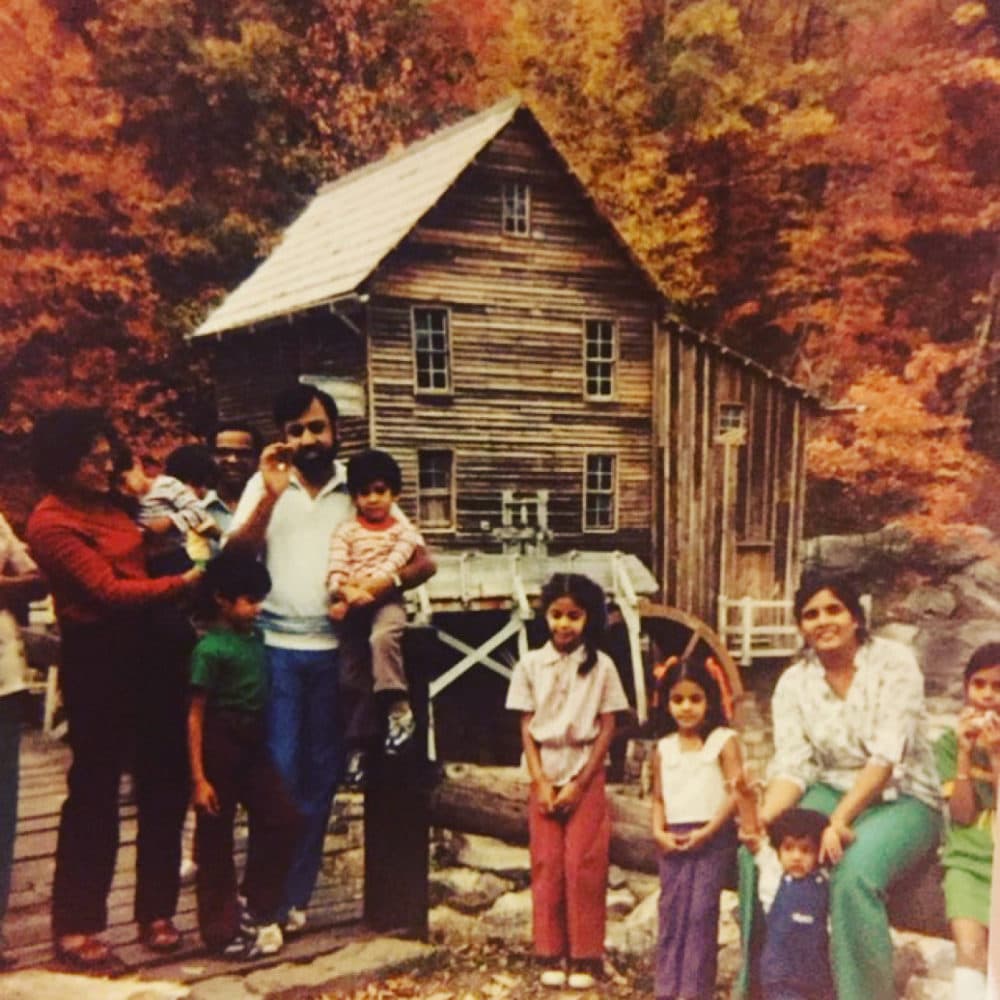

Growing up Indian in Appalachia: 5 questions with Neema Avashia

Editor’s note: Neema Avashia is a regular contributor to Cognoscenti. She’s written several pieces for us over the years, mostly on topics related to education and identity. She’s out with a new book of essays this spring, titled “Another Appalachia: Coming up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place."

Tell us about your motivations to write “Another Appalachia.” What do you want people to understand as a result of reading your book?

For a long time, I considered my experience of growing up Indian in Appalachia as so anomalous, and so unbelievable, that no one could possibly be interested in hearing about them. This wasn’t just a construct I created in my mind. When I told people in Boston that I was from West Virginia, their response was consistently one of disbelief. There are Indians in West Virginia? There are West Virginians in Boston?

But in the lead-up to, and aftermath of, the 2016 election, I noticed that people in New England had a lot to say about Appalachia, and Appalachian people, and their role in the election results. And I felt myself becoming increasingly defensive of my home, my neighbors, my chosen kin. The stereotypes I heard people expressing, the level of disdain in their voices, it just made me feel angry.

People had been sold a narrative about Appalachia and its people that did not resonate for me, and did not reflect the people and place I love. And I realized that while my experience of growing up in that space might have been anomalous, it merited writing about. Appalachia is more complex, and more nuanced, than the dominant narratives about it allow for. I wanted to offer another narrative. I wanted to write the kind of book that makes it impossible to see Appalachia, or its people, in a reductive fashion.

You’ve lived in Boston for almost two decades. How have the last 19 years shaped or shifted your perspective on growing up in Appalachia?

So many of my cultural ways of being are deeply Appalachian, but I didn’t know were so rooted in place until I moved to a context that is culturally disparate. Living in Boston for so long has given me a much deeper appreciation of Appalachian ways of being. A sense of place and the importance of relationships were cornerstones of my upbringing. But they often feel out of step with Boston life.

When I lived in Appalachia, the message I got from so many of the adults was that I had to leave — that there was no viable economic future for me at home. I was eager to leave, to experience city life, to inhabit a more diverse space.

Now that I’ve been away for so long, I can see how much the rest of the country has to learn from Appalachia, where life moves at a slower pace. We got glimmers of it in Boston during the early days of the pandemic, when spending time outside, sitting in backyards or on porches, became the primary way in which we engaged with people. For many, that forced slow down paved the way to deeper relationships — the kind of relationships that are difficult to form when life moves at a more typical New England pace.

Advertisement

Many of our readers and contributors are based in New England – I imagine most of them haven’t spent much time in Appalachia. Why should they be interested in this book, which is grounded in such a different part of the country?

I’m deeply concerned about the level of polarization in our country right now. Our communities are profoundly segregated in so many ways — based on race and class and ideology — that we can end up spending the majority of our time in echo chambers, unable to see why other people might think a different way than we do.

Having lived in such geographically, culturally and politically disparate parts of the U.S., part of what I’m trying to do in this collection is to pull these two spaces closer together. I want to help people in each region see people in the other more clearly. I think that finding a way forward as a nation is going to require all of us to do this. To see outside ourselves and seek to understand the whys behind the choices others make. And I think reading “Another Appalachia” offers New Englanders an opportunity to do just that.

So many of your essays for Cog turn on a story or an anecdote from the classroom. What is the interplay between your job as a middle school teacher and your writing?

I think there are two skills that I’ve built as an educator that you can see reflected in the way “Another Appalachia” is written. One is the ability to ask rich questions — ones that do not have easy answers, and that require deep reflection. The second is the ability to talk and write about complex topics with precision and clarity. Both of these features are present in the essays in the collection.

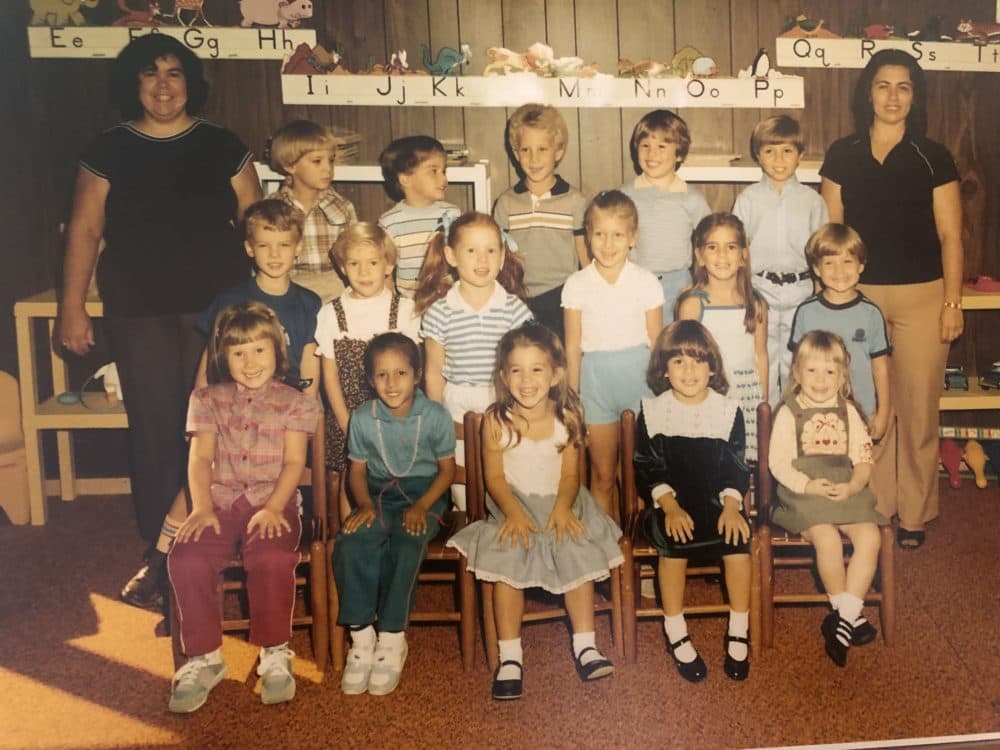

Spending so much of my career with adolescents who are deep in the throes of identity development has taught me a lot about how important it is for young people to have access to books in which they can see themselves — their identities and their experiences — reflected. I didn’t have access to books like that when I was growing up, and it made the process of coming into my own identity infinitely harder. In writing this book, part of what I hope to do is provide a mirror for young people, be they Appalachian, queer, desi, or living at the intersection of all three identities.

As a writer of non-fiction about the place you come from, and the people you love, how did you make decisions about what to include, what to leave out? How do you grapple with the question of what people will think?

“What will people think?” is a question that has plagued the entirety of my existence. If you’ve ever watched Hasan Minhaj’s comedy special, “Homecoming King,” you know that "log kya kahenge?” or the regional linguistic equivalent, is a question so many desi young people have been asked by their parents again and again.

In some ways, I had to put that question away to even write the essays in this collection. Because if I had allowed it to be the question that dictated my choices, there would be no essays; there would be no book.

Instead of “What will people think?” I asked myself questions like, “How am I the most implicated in any story I tell?” and “What was at stake for all of us in dictating the choices we made?” and “How am I holding everyone in these stories with deep empathy?” I used these questions to help me build a better understanding of both myself, and the people that I love. Ultimately, I think that by asking these questions, and writing into them, I am encouraging readers to ask the same questions of themselves, and of the people that they care about. I don’t think any of us learn by avoiding the truth. I think that we learn from excavating the truth with care and tenderness. So that’s what I’ve sought to do.

Visit this link to learn more about "Another Appalachia: Coming up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place."