Advertisement

Commentary

Summer nights are no longer 'a chaos of sound.' Where have all the insects gone?

As summer rolls around, I often think of my childhood in Maryland in the 1970s, and invariably, I think of fireflies. Most outdoor spaces in my neighborhood were tamed spaces — mowed lawns and manicured gardens. Some, however, were left wild, and in summer, these wild spaces overflowed with growth.

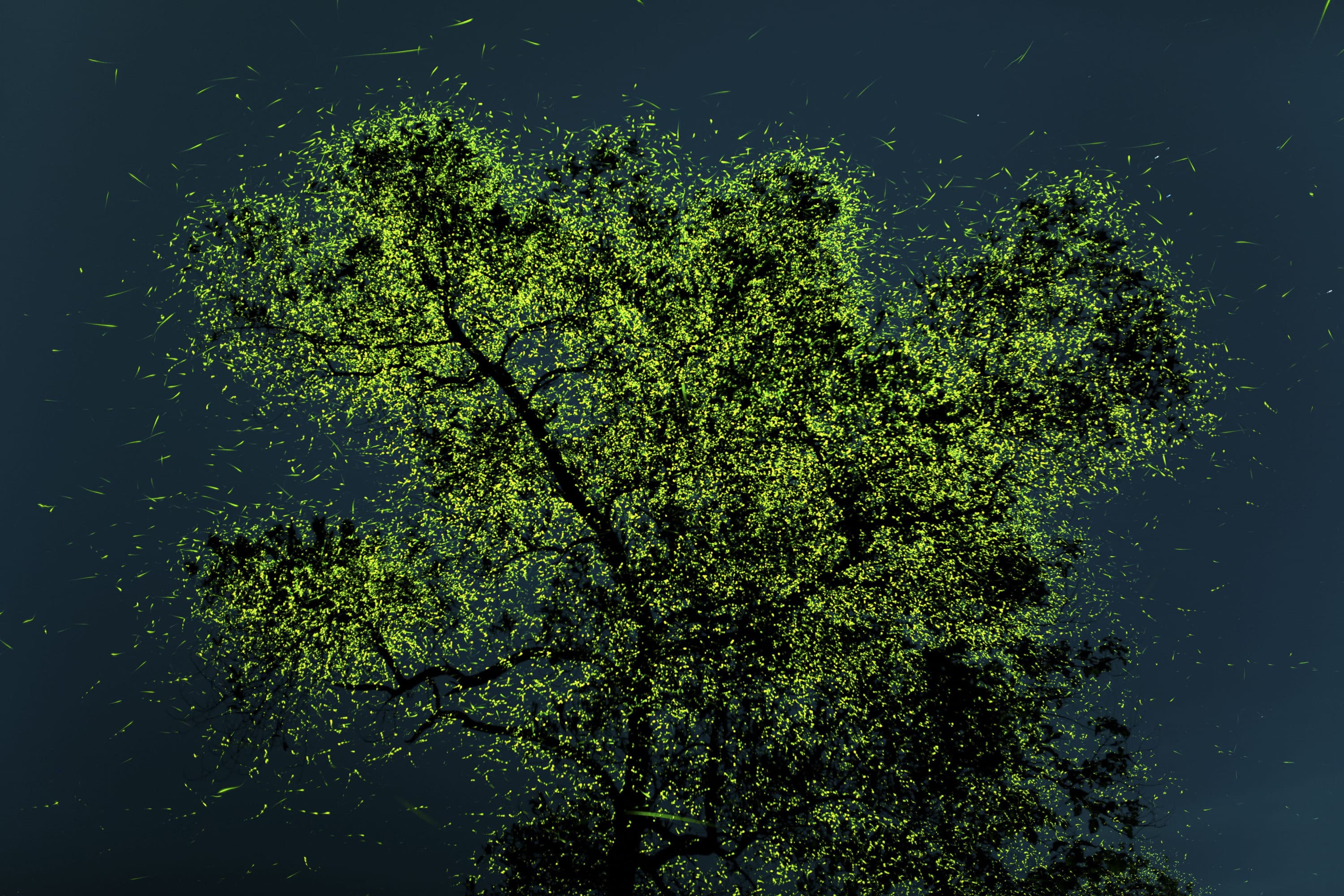

Dark green honeysuckle vines, the shiny leaves of poison ivy, the bright orange threads of the plant parasite known as dodder would drape across bushes and crawl up trees. And all this growth was a haven for insects. As evening fell and I’d look out across our back lawn to the scrub, I might spot a few flashes of firefly light and then, as the sun slipped further under, I’d see so many more, twinkling and streaming against the darkening backdrop.

The fireflies were by no means alone. The flashing of their lights was accompanied by the chirps of crickets and shrieks of locusts, a cacophony of insect sounds that blended in the air to a unified hum. The noise betrayed to our ears the sheer number of insects that were out there and in what astonishing variety. The show these insects put on was the most punk rock performance I’d ever experienced. It began before sunset, lasted until dawn, obeyed no limits, and followed no rules. The same heat and humidity that slowed the pace of our lives were an accelerant to the insects. They pupated and emerged, some after years underground, to raucous celebration, ravenous consumption and a race towards reproduction.

The show these insects put on was the most punk rock performance I’d ever experienced.

Are summers full of insect sights and sounds a thing of the past? Environmental experts have been measuring wild insect populations for decades. In recent years, the news has been dire. Writing in Current Biology in 2019, insect ecologist David Goulson cites studies done in Germany and Puerto Rico that report staggering declines over the last quarter-century in both total insect biomass and species diversity. In one of these studies, the total insect biomass collected in the wild by researchers in 2014 was less than a quarter of what it had been using the same methods in the same location in 1989.

Goulson points to several economic reasons we should pay attention to insect declines. He notes, for example, that three-quarters of the crop types we grow require insect pollination, “a service estimated to be worth $235 to 577 billion per year worldwide.” He further appeals to our sense of natural wonder, asking, do not all species have as much right as we to be here on the planet?

Why is it happening? The proposed causes of insect declines are all too easy to imagine. In a research article published in the journal Nature in April of this year, Outhwaite and colleagues reported that insect declines are at their worst in those places on the planet where large-scale agriculture and the impacts of climate change coincide. A glimpse of hope comes from the observation by Outhwaite and colleagues that the presence of natural spaces nearby sites of low-intensity agricultural use — spaces akin to the wild patches that abutted mown lawns in my old Maryland neighborhood, but on a much larger scale — dampens the declines compared with sites lacking nearby cover.

The declines in insect populations are alarming. The issue is one symptom among many that we are not treating our planet as we should be. As a nature-loving kid who grew up to become a biologist who studies an insect (the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster), I find that it’s a symptom of environmental distress that particularly resonates with me.

I believe that radical societal change on a global scale is needed in order to save ourselves — and the fireflies, the crickets, the locusts and so many other invertebrate beasts — from environmental destruction and climate change. Yet I find myself wondering when our society will bend to meet the need.

How quiet must the summer nights become? How devoid of the magical flashes of light? The chaos of sound? The raucous lives of the small?