Advertisement

Commentary

When abortion is 'an unimaginable act of surrender'

A few months into my first pregnancy, I was running through the woods when an owl lunged at me. The bird sank its talons into my ponytail and gave a hard tug. We squared off for a second and then I bolted, waving a stick above my head. When I told my best friend about it, she texted: “Don’t look up the symbolism behind owls.” I jumped online.

In North America, owls are known as messengers of death. As an anthropologist, I am trained to decode cultural symbolism, or at least take note of it. I tried not to obsess about my owl encounter, but I worried. I didn’t want it to be an omen — especially not in relation to the new life I carried.

When I passed the 12-week mark in my pregnancy — the ostensible “all-clear” threshold — I relaxed. I started picking out names and a crib. Jubilant, I told everyone I knew.

Then, at my 14-week prenatal visit, clinicians couldn’t detect a fetal heartbeat. One after another came in to press the cool, slippery end of the ultrasound probe into my belly. I could read the news on their faces before I heard it from their lips. Likely, they said, the fetus had been dead for two weeks.

[H]ow compassionate is this vision of life that would have required me ... to deliver a fatally sick child into inevitable misery?

I remember the urge to lie down in a bathtub full of ice chips and not wake up for a long time.

I was given the option to either go home and take medication to expel the remains or undergo surgery the following morning. As much as I wanted this baby, I couldn’t bear the idea of holding its tiny corpse a minute longer. I opted for surgery, a dilation and curettage — twice, because the doctors failed to get everything out the first time.

A few days later, when the results of the genetic screening came back, I learned my boy had Trisomy 13 — a rare genetic condition that causes severe abnormalities of nearly every organ in the body, including the brain. Half of all babies that survive until birth die seven to 10 days later; 90% die within the first year. If this child had been born alive, he would have suffered beyond measure, and I along with him.

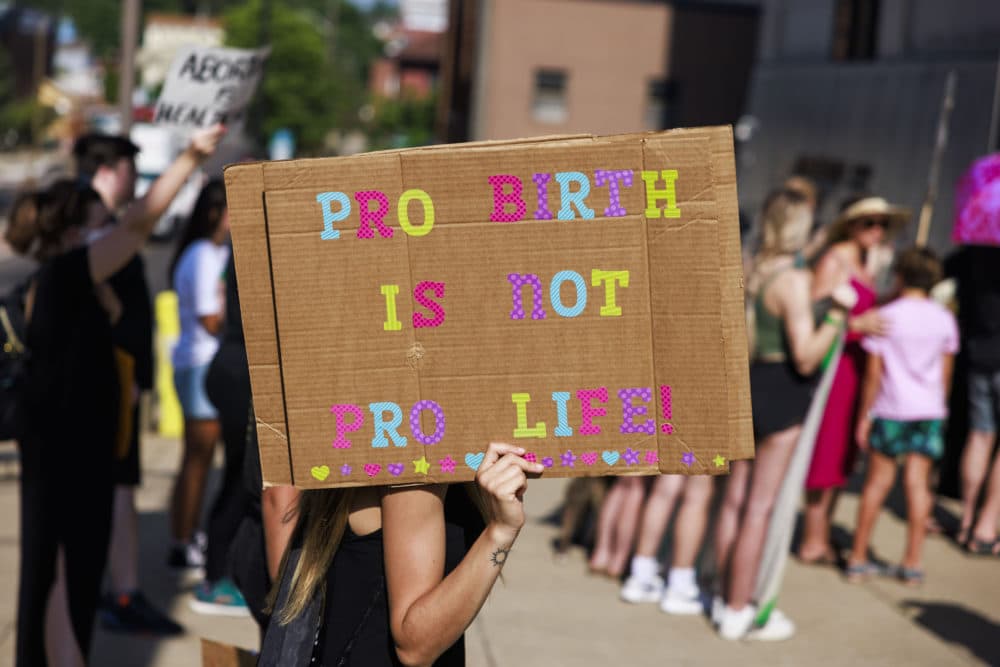

When pro-life advocates speak about the importance of protecting unborn life, I want to agree with them. Pregnancy carries the seeds of a possibility, the imminence of a potential life. But how compassionate is this vision of life that would have required me — had my son survived to birth — to deliver a fatally sick child into inevitable misery? At what point does suffering annul life’s value?

At what point does suffering annul life’s value?

And if life is unambiguously sacred, why does the life of the birthing person mean so little? Banning abortion post Roe will create tremendous suffering for those who face pregnancy complications (ectopic pregnancies, placental abruptions, cancer diagnoses) — all traumatic in themselves, but even more so without the guarantee of timely deliverance.

“Deliver” can mean to “set free” or “surrender.” Terminating a pregnancy is an unimaginable act of surrender. It is letting go of what could have been to accept what is.

A similar promise of deliverance is at the center of my professional work on the end of life. Terminally ill patients who opt for assistance in dying often do so because they find neither purpose nor meaning in their suffering. Time and again, the people I worked with said that the quality of their life was zero. They cherished the ability to direct their own ending.

But that didn’t mean they regarded life as expendable. Many viewed the choice to hasten their own death as the most life-affirming act of all, because their illness had robbed the life they loved of its inherent worth.

Like death, birth holds the potential for great suffering, physical and otherwise. If a pregnancy is unintended, undesired, unsupported or unviable, it can spell the prospect of a future in which neither the parent nor the child will flourish. Releasing that life is a painful, excruciating choice — and sometimes not even a choice at all.