Advertisement

Commentary

I ‘Marie Kondo’d’ my teaching during the pandemic. Now, I’m sticking with it

What started as a small moment on a middle school student’s zoom screen way back in September 2021, that first pandemic school year, would change the course of my teaching in ways I could never anticipate. Trying to replicate the classroom experience we’d always had — as much as possible anyway — I was still insisting cameras be on all the time. I was reading and acting out a story in Latin that my students were supposed to be drawing, and a student’s little sister, still in pajamas, slipped into the frame and asked for help braiding her hair.

Remote-learning often excluded older siblings in minoritized communities who shouldered the sudden burden of childcare during the pandemic lockdown. As I watched that student braid her sister’s hair, I considered the likely reason why she had been almost completely absent after we pivoted to virtual learning during the end of the last school year. I felt so much more respect for her finding a way to be present.

This pandemic school “aha moment,” as well as conversations with my colleagues about theirs, made me question and reassess everything I used in the classroom. So much felt heavy, overwhelming, and the only way I could lighten the load and lower anxiety was to somehow do more with less. So, I began to clean and sort. I looked at each method or assignment, held up each part of my teaching, and considered, “Does this really help students understand Latin?” If it didn’t, I tossed it; a curricular Marie Kondo-ing.

I ended classes with a few quick comprehension questions about the Latin story we were reading. This let me see that grammar charts, however cherished by teachers like me, failed to help students understand the language. With fear and trembling, I said goodbye to grammar, and hello to more reading with vocabulary support. I noticed how keeping assignments small and frequent decreased student anxiety. This made them less afraid to dive into the language.

Zoom was a wretched medium for acting out stories, but a beautiful medium for students to share their artwork and writing. Finally, we found a way to build community with shared characters and jokes. Every character had a zombie (zombius) or werewolf (versipellis) version and the enslaved male cook from our textbook became a goddess (Grumio est dea).

Around winter break I finally took out one of my old tests, made it just 10 points like every other assignment, and gave it in a Zoom session. I was nervous. Would this year’s students, learning in an entirely different way and with the changes I’d made so far, do nearly as well?

They did. Even the kids who hadn’t done any of the homework demonstrated understanding of a large part of the story. Every chapter after that I gave a similar reading check. Every kid showed acceptable, at least C-level progress; a handful without turning in most of the homework. Something was working.

Everything that does not directly lead to student learning of the subject matter is a barrier to someone.

Then — gloriously, terrifyingly — we were back in person. I braced myself for grades to fall in reading assessments now that students didn’t have access to Google translate and couldn’t text each other off screen for answers. Instead, they went up! And it was official, some students seemed to be learning just as well without homework.

I remembered my student lovingly doing her sister's hair as we’d worked. I had already killed off grammar, vocabulary, big tests and now the last sacred cow; I took a deep breath and cut out the homework. I watched those daily checks like a hawk and was floored when, even without homework, students’ reading comprehension kept improving at the expected pace.

As I prepared for the second pandemic school year, this time fully in-person, a tiny thought snuck in. The end of the that last year had gone so well. Students were suddenly able to collaborate more easily and remote work was replaced with skits, conversations and the chaos of making armor for our gladiator games. Everyone was suddenly engaged and doing well on their reading assessments.

So I began to wonder if I could teach in such a way that none of my students felt lost? In which no one gives up? Could this most inaccessible of languages — Latin — be accessible to everyone, this subject that has so often been a gatekeeper for elite white academic spaces?

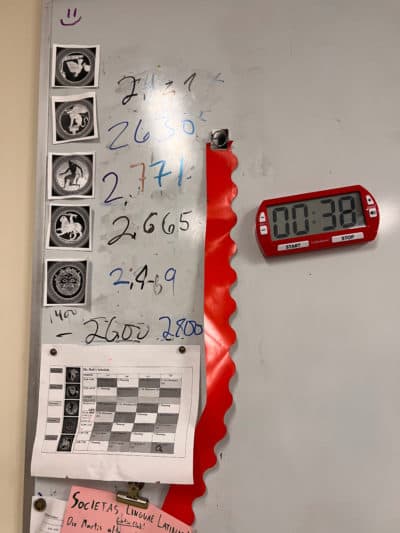

As I taught that first month, I intently followed my daily checks. For the first time, if I saw grades dip for more than a day, I either retaught material or emailed parents to simply ask if they could quiz their student in vocabulary or read one of our stories together. Emailing parents takes time, but I no longer had to grade homework, vocabulary quizzes or tests, so all that time and energy went into direct student support. Then I gave a longer reading passage. Not only were there no D’s or F’s — the vast majority were A's.

With every larger reading assessment I gave, I held my breath. Surely, cutting such long and lovingly followed methods of instruction would hurt learning, but the success continued. I did cover a little less material, but students were actually willing to do a little extra work to catch up, because I never let them fall so behind that they felt hopeless. Amazingly, I also found that I wasn’t growing increasingly exhausted like I had in previous years.

Now, I know Latin is different. There are no standardized tests to teach to, and I am usually left to my own devices since I am the only Latin teacher in my school. I am also lucky to have innovative colleagues and administrators who provide excellent examples, offer feedback and allow me to explore new ways to get better results.

I’m here to tell you, however, we aren’t going to fix education by adding more things for students and teachers to do; we are going to fix it by evaluating and removing things that don’t work.

Everything that does not directly lead to student learning of the subject matter is a barrier to someone. And as for my students and me? We’re not going back.