Advertisement

Commentary

May we honor their sense of wonder

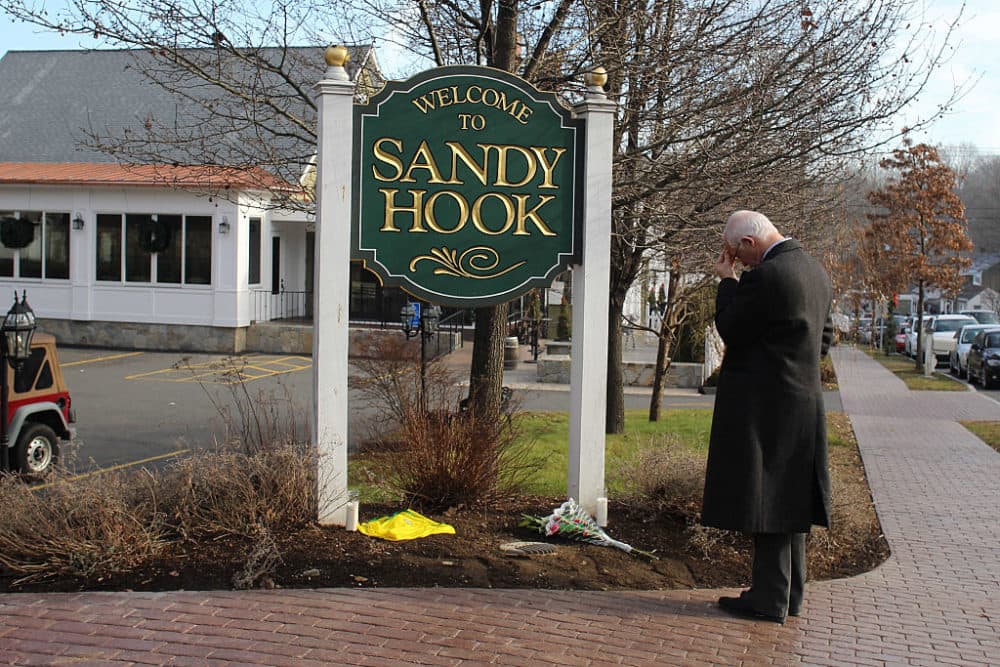

Editor's note: Leah Hager Cohen wrote an essay for Cognoscenti just a few days after the Dec. 14, 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Conn. Ten years later, we asked her to reflect on that gruesome tragedy.

Ten years have passed since the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. On that Friday morning in December a 20-year-old shot dead 28 people: 20 first-graders, six staff members, his own mother and himself. There was no making sense of it — not only no motive in this case, but also no explanation for why mass shootings were, even then, so prevalent.

How was it possible that yet another person possessing the lethal combination of mental illness and guns had been allowed to commit such an atrocity? Didn’t we as a society already have achingly ample acquaintance with the problem? Shouldn’t we have devised a solution?

There was no making sense of it, but wasn’t there — briefly, briefly — hope? Didn’t we think for a moment that this might be the event to bring about real change? Even as members of a populace grown increasingly numb to such tragedies, weren’t we profoundly jolted by this one? Wasn’t there something about the terrible quantity and the extreme youth of the littlest victims that would shake us out of our stupor at last?

They were so small, the murdered children. They were 6 and 7. The age of hilariously botched knock-knock jokes, the age of wiggling your loose tooth with your tongue. The age of exquisite curiosity. The age of boundless questions.

Within hours of the shooting, leaders from around the globe had expressed condolences; gun control groups had received so many online donations their sites crashed, and the president had cried on national television. Surely this time, we may have hoped, there would be enough societal, political and corporate will to bring about change at last.

Ten years later we know any such hope was misplaced. The intervening decade brought no substantive achievements on either gun control or mental health care. What it did bring: more than 3,500 additional mass shootings, and an increase every year in the percentage of people with mental illness who report unmet need for treatment. What it also brought — and this, too, started within hours of the shooting: conspiracy theorists who accused the grieving family members of being “crisis actors” perpetrating a “hoax.” Their relentless campaign resulted in an ongoing form of torture, as the bereft were hounded for years by abuse and threats of violence.

Typing those words boggles the mind. If it’s hard to fathom what the shooter could have been thinking and feeling, it’s that much harder to fathom the actions of the conspiracy theorists and their followers. When I try, I find myself reduced to questions of 6- and 7-year-olds. What? Why? Who could want to hurt people in this way? How can we get them to stop?

Advertisement

On a practical level, we can develop better tools, and better use existing tools, for disarming those who would cause such harm. Votes, laws, dollars, health care, education, the courts — these are all practical tools. We saw an example of how the last could be effective just this fall, when juries delivered verdicts that removed some of the conspiracy theorists’ wealth and power. But as satisfying as those verdicts felt when we saw them splashed across headlines for a day or two, they don’t address the underlying sickness.

What makes people hate other people? What makes us fall prey to the delusion that we’re not all connected? How can we remind ourselves that we are?

We can and must continue trying to use all these tools, and at the same time we need to recognize that none of them work well when the society they’re meant to work in is unwell.

In the decade since the Sandy Hook shootings, the signs of sickness, of brokenness within our society have only mounted: neighbor pitted against neighbor, families fractured from within, the readiness to demonize those from whom we differ. Are any of us blameless?

I find myself returning to — and not in fact reduced, but rather elevated by — the questions of 6- and 7-year-olds, of those who wonder truly, those who have not given up on trying to fathom: What makes people hate other people? What makes us fall prey to the delusion that we’re not all connected? How can we remind ourselves that we are?

When my mother was dying, she observed, “People just want to be loved.” All her life she’d been smart in a dazzling, complex manner, but towards the end her intelligence grew distilled and elemental. She became wise in a simple way. “Try to love them,” she said.

Whenever I imagine how I might respond if involved in a mass shooting, I always see myself moving to embrace the shooter. Is this shameful? Certainly it’s grandiose, unsupported by any act of bravery I have undertaken in real life. Still, perhaps because of my mother, it’s what comes to mind: the imperative to reach toward the humanity in others, even those who would cause harm.

And yet, even in my mind, I fall short. I don’t know how to love Adam Lanza. I don’t know how to love Alex Jones. I don’t know how to love Donald Trump or Derek Chauvin or Nick Fuentes. Increasingly, as the stakes grow higher, I struggle to love even some of my neighbors.

But here is what I can do: commit to being curious about them. More than a choice, I believe it is a duty. A duty to myself — to my own humanity — as well as to the society every one of us helps make. Being curious is like opening a door; I suppose that’s why it’s considered dangerous. But how much more dangerous it is to become a society of the resolutely shut door, the refusal to wonder, the refusal to ask questions and listen and share.

Perhaps this is one way to honor the memory of those 6- and 7-year-olds: by making a commitment to try, collectively, for some measure of exquisite curiosity.