Advertisement

Commentary

Life and death on the gridiron

Football fans are still reeling from the images of Monday night’s game between the Buffalo Bills and Cincinnati Bengals, during which Damar Hamlin collapsed after a violent collision and went into cardiac arrest. The 24-year-old plays safety for the Bills.

His heartbeat was restored on the field, and he was transported to the University of Cincinnati Medical Center, where he remains in critical condition. The players, many of whom were in tears as Hamlin lay, unmoving, on the turf, were sufficiently anguished that the game was suspended. They knew, after all, that it might well have been them on the ground, hovering between life and death.

None of this comes as a surprise anymore. Even the most diehard football fans understand that there’s a reason every NFL stadium has an emergency protocol in place, with paramedics and an ambulance on standby.

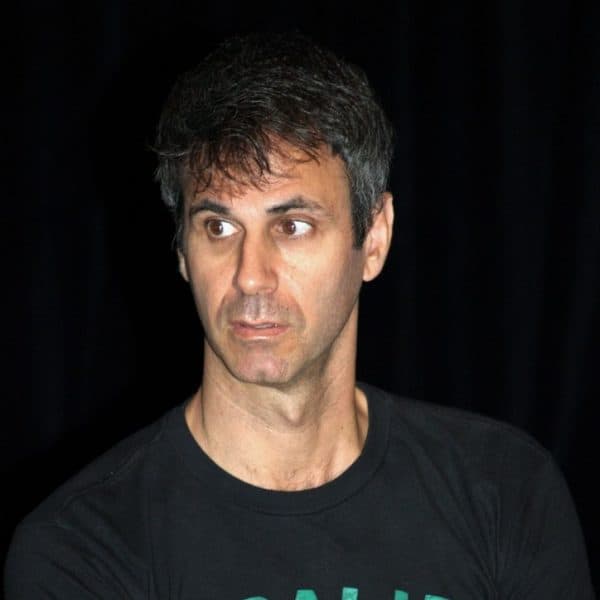

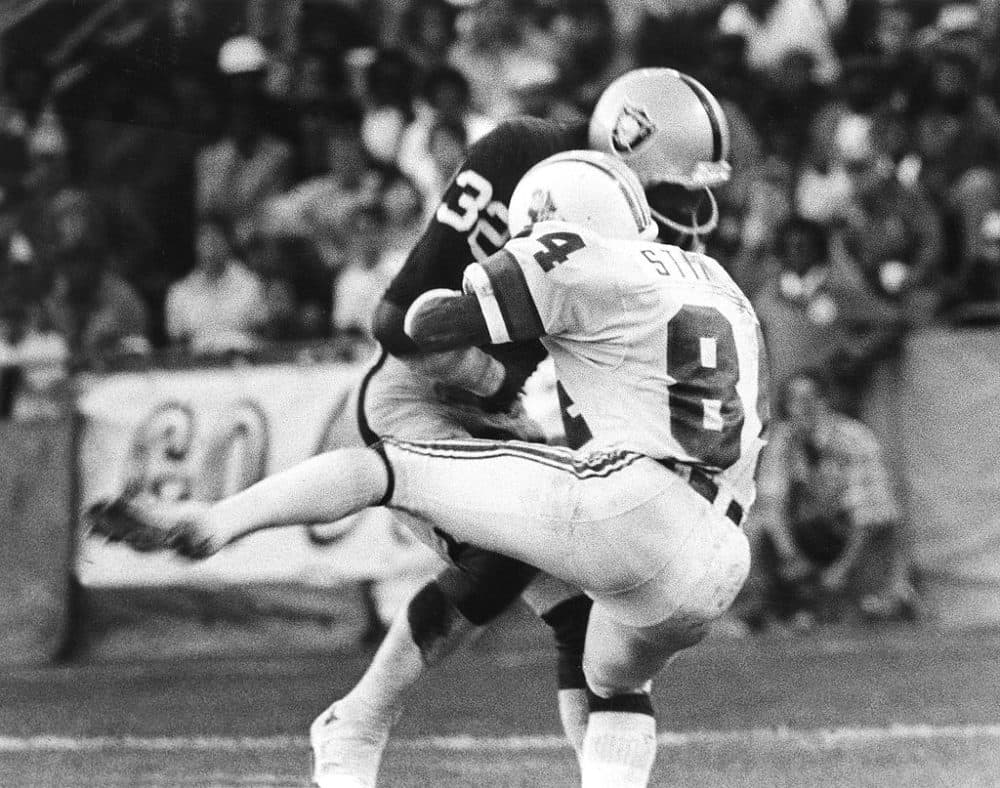

Heck, I’ve known the game was lethal ever since I watched my childhood hero, Jack Tatum, deliver a vicious hit that left Patriots' wide receiver Daryl Stingley paralyzed for life. That was back in 1978. I was 11 years old. I expected the adult world would shut football down.

But that’s not what happened. After a brief period of remorse, all us fans—me included—went right back to watching. As a spectacle, the game is simply too pleasurable, too popular and thus too profitable to fail.

This is how it’s always been with football. In 1904 alone, at the dawn of the sport, 18 players died, most of them prep school boys. Dozens more suffered grisly injuries: wrenched spinal cords, fractured skulls, and so on. Editorial writers condemned football as too brutal for civil society.

When President Teddy Roosevelt learned that his alma mater, Harvard, was considering banning the game, he convened a summit of football authorities, hoping to “minimize the danger” by introducing reforms such as the forward pass and a neutral zone between offense and defense.

It’s worth noting the language Roosevelt used in framing his reforms. For instance, he wanted to make sure the game wouldn’t be played “on too ladylike a basis,” and stressed that he believed in “… rough, manly sports. I do not feel any particular sympathy for the person who gets battered about a good deal so long as it is not fatal,” he said.

To the modern ear, statements like this smack of toxic masculinity. But that’s the allure when it comes to the kingdom of football: it’s a realm where the gender values are essentially medieval. Men are warriors who triumph via aggression. Women are sexual objects who jiggle on the sidelines.

Football promotes plenty of positive values, of course: courage, perseverance, cunning, cooperation. There are moments of grand drama and remarkable grace. Anyone who attempts to reduce football to pure brutality will never understand the game, and thus why it’s so beloved.

But as someone who has been in the thrall of football for more than four decades—often reluctantly—I’ve come to view our collective devotion to the game as the embodiment of an American penchant for tolerating, and even reveling in, violence.

It is not some crazy coincidence that our country is the only industrialized nation that refuses to enact sensible gun control, and thus suffers scores of horrific mass shootings every year. Nor that our popular culture is awash in violent imagery. Nor that our political culture, especially on the far right, has become increasingly fixated on using violence as a means to gain power, as happened when rioters stormed the Capitol on January 6. They are enabled by figures such as Rep. Kevin McCarthy, who is so eager to be elected speaker of the House that he’s been happy to excuse such violence.

I’m not suggesting that football fans are the cause of any of these societal problems. But these problems are symptoms of an American illness, arising from the same psychological conditions that make it possible for adults like me to continue to watch football. Namely, the conscious suppression of empathy, and the ability to embrace cognitive dissonance.

Which is to say: the same players who were weeping over the potential death of a comrade a day ago will be back this weekend to play another game. And the fans who offered “thoughts and prayers” to Hamlin and his kin will be on-hand to watch.

So will the paramedics and the ambulance driver.