Advertisement

Commentary

My life in Cuisinarts

You can divide most lives into distinct periods: childhood, adulthood, finding a partner, children, career and retirement. My life is more easily divided into three Cuisinart eras. There’s Cuisinart infatuation, Cuisinart breakup and Cuisinart rebound.

I was only 15 when the first Cuisinart era began. Here’s how that happened: I loved cooking as a child. I made zabaglione, a custardy Italian dessert, in a double boiler when I was 10. I still have the faint line of a scar I got at 11 when I tried to slice potatoes on a mandoline for the first time. By the time I was a teenager, I was making puff pastry.

At 15, I got a part-time job at Cook’s Corners, a cooking supply and catering business in Westport, Connecticut. The owner would invite famous chefs to give cooking lessons, including the irritable Simone Beck, co-author of “Mastering The Art of French Cooking” with Julia Child and Louise Bertholle. Beck cooked with a cigarette dangling from her mouth.

One afternoon in the early 1970s, a man named Carl Sontheimer visited the shop. If you look up his obituary in The New York Times, you’ll see he revolutionized American cooking around that time. One of the places he began that revolution was at a table in our store, where he brought a machine called a Cuisinart that he said, “Julia just loves!”

The machine sliced, shredded and pureed. It made pastry. It pulverized nuts. It did the kind of things that would have burned out a blender’s motor. An average cook could turn into a gourmet cook — quenelles! duxelles! cream puffs! — overnight.

I bought one, for $175, with the money I earned at the store. I brought it home, and a subtle change happened between my mother and me. All of a sudden, I could make fancier and more time-consuming things than she could. The power the Cuisinart gave me in the kitchen became an almost measurable thing. It provided an awkward and lonely teen girl with the confidence I could not get from any other part of my life. From baba ganoush that reflected my father’s Middle Eastern heritage to French soufflés mirroring my mother’s taste, I tackled hard things and fed my family the results.

I brought that Cuisinart to college with me and cooked feasts for my classmates at the end of each semester, whirring, slicing and chopping ingredients late at night after handing in my final paper. I earned money with the Cuisinart, doing catering on the side. I took it abroad during a year off; I hauled it to San Francisco post-college. I had that gray-and-white machine for almost 25 years, through a courtship and marriage, then two children and a divorce. It never once faltered, from chopping onions to grating carrots to pureeing chickpeas and making baby food.

I’m ashamed to say that I don’t remember what happened to my first Cuisinart. All I know is that sometime in the late 1990s, I moved to Maine with my family. The Cuisinart stayed in California. I bought a new one. Thus began the second Cuisinart era. But this one was different: I broke up with it.

I was now a single mother and a writer. Both were rewarding roles, but each was also frustrating. Being a single parent means answering all the questions, making all the decisions and choosing between impossible choices — every day — including how to be in two places at once. And writing successfully takes time: Your words and phrases don’t emerge perfectly polished. You’ve got to revise, revise and revise. I needed to find gratification and something contemplative to do, to ease my jangled single-mom nerves.

My answer was a sharp knife.

When I cooked, then, it wasn’t the Cuisinart chopping things, it was me. Starting with a bag of carrots and my chef’s knife, in about 20 minutes I’d chopped a neat pile that would become soup. Weekends were for bigger projects: I’d dice 15 pounds of tomatoes, throw them in a kettle with sugar, grated ginger and spices, and by later that afternoon I’d made 15 jars of tomato jam. The rhythm of cutting, the growing piles of chopped fruits and vegetables that I turned into everything from lentil soup to fruit cobblers, gave me satisfaction. Also, it gave my kids dinner.

Now, 50 years after I fell in love with a Cusinart, and many years after I fell out of love with it, our affair is on the rebound.

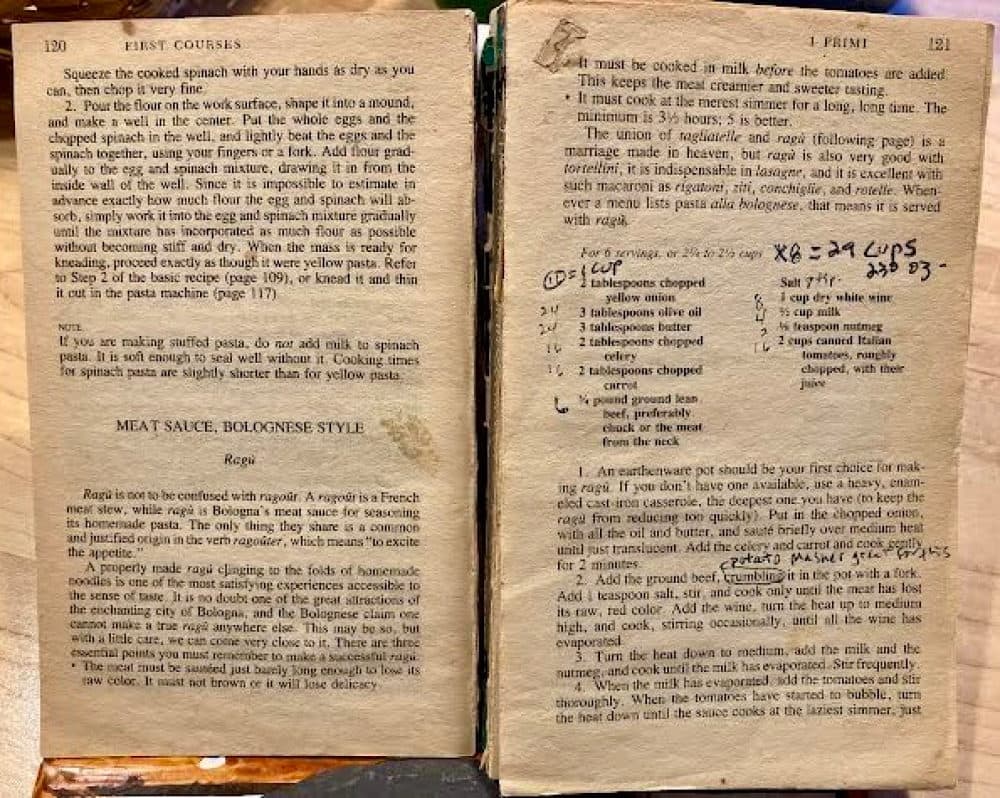

I’m 65, my hands and wrists complain a lot, and the only way I can keep cooking for my family — expressing my love with Bolognese sauce, apple-cheddar cobbler, beef carbonnade — is to take that hunk of plastic and metal out of the cupboard and plug it in. My husband always offers to help with tasks that require using my hands, and sometimes I let him. But I’m at a stage in life when I don’t want to lose the ability to do things. That feels like growing old.

So, if once my Cuisinart gave me the power to grow and mature in the kitchen as a teenager, now it gives me the power to slow down time and keep doing the things I have loved, making food for my family and friends. This sturdy machine gave me confidence as a girl to make the pastries and sauces and stews that helped build my identity as an adult. Now, it allows me to remain that person, the same one who, all those years ago, found peace and purpose in a kitchen.