Advertisement

Commentary

I'm a poet. And I celebrate the days I write nothing

During the 30 days of April, poetry, normally not-in-the-limelight, earns a hashtag: it’s #NationalPoetryMonth. It's as though Emily Dickinson has won a Publisher's Clearinghouse prize. There's a major uptick in poems studied, written, performed, and published as poetry becomes the focus of national educational organizations and local community arts counsels, heralded by U.S. Presidents and English language arts teachers alike.

I've been writing and publishing poetry since I was 15. It's usually a quiet gig. Come April, though, my day planner is flooded with readings, public appearances, online events, interviews and contests to establish or judge — and I'm only a state poet laureate. I can't imagine what U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limon's calendar looks like for those four weeks. All this fanfare for a genre that won't be touched by most literary agents.

April's flurry of poetic involvement started in 1996, when the Academy of American Poets designated the month as National Poetry Month, for the noblest of reasons. The intent is to support writers and make poetry more accessible. What I also celebrate during National Poetry Month is poetry's special capacity to engage with uncertainty and stillness. Walking toward — rather than running away from — emptiness establishes a special mindset. It's an outlook that's sufficiently vacated of preconceptions and self-criticism, and it helps us notice creative possibilities.

I learned the hard way.

I didn't pick up these lessons about not-writing, which I joyfully practice every day desk-side, January through December, from a teacher, a poetry book, a graduate degree or a TED talk.

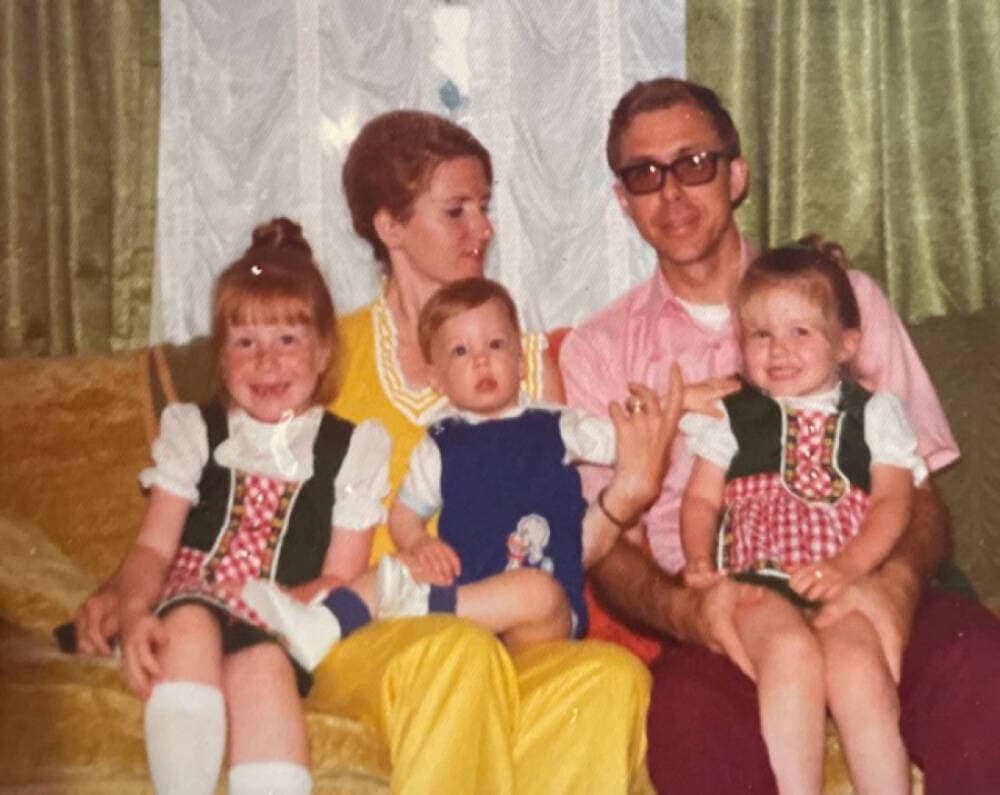

I first started noticing creative emptiness as a 6-year-old on a hospital bed in a children's ward, after surgery for complications from an anti-morning sickness prescription — likely DES — my immigrant mother took while pregnant with me.

What put me in that hospital room was a birth defect on my bladder and ureter, the first in a series of anatomical peculiarities that by adulthood would make me resemble the board game Operation. Just as plastic tweezers move around plastic organs in the game, parts of my anatomy had been redesigned or relocated in my torso, requiring medical intervention. Post-op, medical professionals would come find me in recovery, still groggy, to request to keep my body part in the formaldehyde jar or point to an illustration in a medical textbook.

Advertisement

Because the reasons for my physical conditions were initially not known, and then not disclosed to me until I was in my early forties, I started searching behind what parents and doctors said. In that hospital bed, surrounded by a Harvard specialist and his interns with their clipboards, listening to them discuss my case, the 1970s “boy in the bubble” loomed in my thoughts. I was often alone, hoping a parent would appear during visiting hours from their shift at the convenience store. Important personal information was withheld, replaced with innuendo that I wasn’t destined for a normal life. And so, early on, I rejected the narratives about me. I sensed a more internal truth, one that could be accessed from a moment-to-moment alliance with my own body.

Sitting with creative emptiness means accepting with self-compassion the times when you want to write and you can't.

Still, it took me until my next hospital bed 30 years later — on bed rest in a high-risk pregnancy ward at Brigham and Women's Hospital — to really figure out what I now think of as creative emptiness.

I was burdened with writing blocks throughout two MFA programs in poetry because I often became depressed, associating prolonged verbal blanks with hospital loneliness. Until my water broke 13 weeks premature, I'd wander into brief stretches in which I finished poems (one took nine months of daily work, the gestational metaphor not lost on me), but only with great straining against my perceived isolation. This ended with my daughter Sophia's precarious birth. I stopped fighting off the emptiness around words. Separated for many weeks from my baby in a neonatal unit in Boston — whose fate was at times touch and go — back at my desk, 60 miles away in New Hampshire, I entered the moment, and my sorrow, at my desk.

I sat with the emptiness. And it called back. That was 18 years ago, and it hasn’t stopped since.

Sitting with creative emptiness means accepting with self-compassion the times when you want to write and you can't. It means recognizing that every typed word sits between two gaps and that, when we write, we are as much beings of silence and waiting as language and typing. It's dropping the constant striving for results, or the desire to be someone we're not (more creative, more successful, fill in the blank).

The thing is, when we misperceive the nonverbal moments in our writing life — such as the faceoff with a blank page — as idleness at best, incompetency at worst, we miss how these pauses happen all the time at the desk. Not-writing is not only natural: it's productive. During not-writing, we gain insight from our bodies and unconscious. No matter which genre we write, our readers are imaginary beings, creatures who reside in an upcoming moment, separate from us in space and time. We act as though we're performing for readers in real-time as we sit at the desk, but we're only in conversation with ourselves. When we stop participating in that unhelpful illusion and learn to be our own audiences, including listening to our silences, writing happens.

The paradox is that we're never empty for very long. When observed even for a few moments, creative emptiness transforms into creative fullness and back again to emptiness. Empty. Full. As the Heart Sutra, a kind of poetry to me, says: "Form is emptiness, emptiness is not different from form, neither is form different from emptiness, indeed, emptiness is form."

Poetry is the perfect vehicle for detaching from outcome fixation, gaining space from difficult future-based audiences, and building motivation, all steps in a mindful writing practice. In its page appearance, poetry highlights how it's an interaction with letting go, with emptiness, with the gaps, with the interplay of said and unsaid.

So, as we near the end of National Poetry Month 2023, let's honor words and the moments between them. It'll bring us equanimity and calm, not to mention more poems to poets.

From "The Water Draft" (Spuyten Duyvil 2019), Alexandria Peary

"Writer's Desk as Shrine":

Glassblower, I breathe in / breathe out,

making my temporary vases

on display under the desk.