Advertisement

Commentary

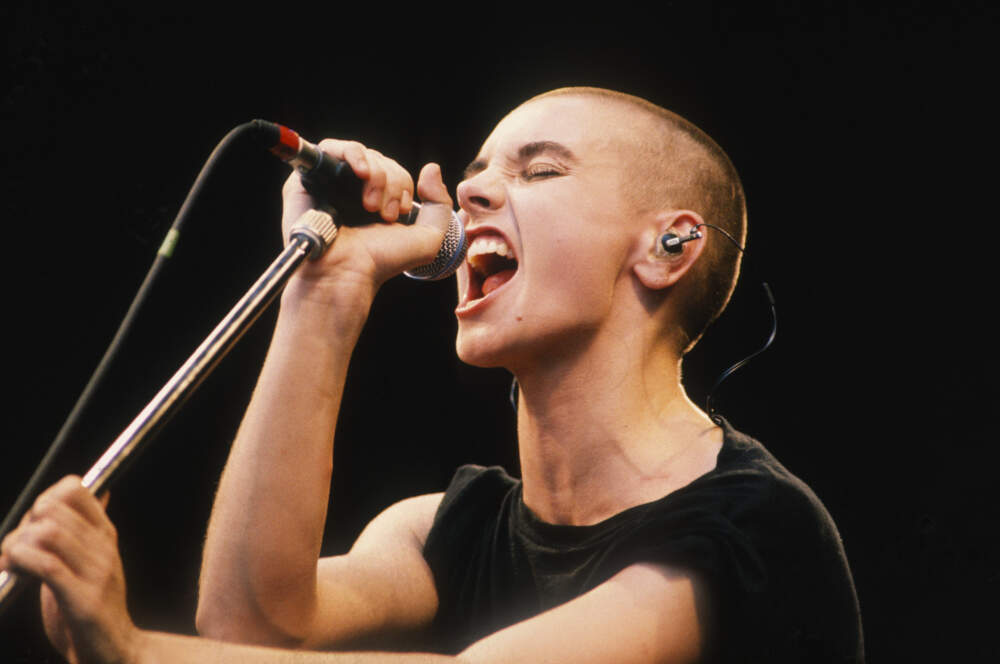

I loved Sinéad for her wild courage and rage

In 1992, even in New York City, it did not feel safe to question my sexuality. It was another world then. I was 19 and living on my own with the whole city outside my tiny apartment, and all I knew was that inside of me, a storm was raging.

Sinéad O’Connor helped me understand what it was.

I grew up in the city and chose to stay for college because I wanted to experience life there as an unsupervised adult. I did that to the fullest: part child of nightclubs and music subculture, of darkness and rebellion; part straight-A student and bookworm, overachiever, autodidact; all parts overthinker, late-night coffee-drinker, insomniac, notebook-scribbler, ponderer, self-tormenter.

At that time, I was still reeling from the suicide of my first love, just over a year earlier. That relationship had been torture for both of us: for him, because his love for me was not enough to release him from his demons, and for me, because I, only a child of 15 when I met him, lost myself in trying to save him and confused love with putting my own life on hold. In the wake of his death, I felt despair mixed with guilt because I wanted to keep living but I did not know how.

Music was solace. Healing. It always had been. I stayed out dancing until the clubs turned their lights on, only to fall asleep to more music. I did my best thinking as I walked to and from classes and work and clubs, up and down the island of Manhattan, with my headphones on my ears drowning out the sound of the city. I stomped as I walked, in my big black platform boots. I fussed. And I raged.

I found Sinéad O’Connor during that time. She was already well known by the time I discovered her gorgeous voice. When a few of my classmates and I piled into someone’s car and drove to Washington, D.C. for the March for Women’s Lives March in April 1992, someone put on Mandinka, and the world stopped.

In D.C. I never did march. I stayed on the sidelines, sitting in the grass in the shade because my friends met up with some friends and one of them caught my eye. She was impossibly sexy, so cute sitting there cross-legged, with her pixie cut dyed cherry red, cat-eye glasses, a baseball jersey shirt and hoodie. She had a bumper sticker stuck across her back that said "Not every sperm deserves a name."

“Is she … ?” I asked my friend Mary, my only confidante. We didn’t even dare say it aloud back then. She had recently confessed to me that she and her roommate, Emily, were not just roommates, but, of course, I was sworn to secrecy.

“She is,” Mary whispered, “but she isn’t telling anyone. Except you.”

She drove a stick shift red Honda Civic down to see me from Westchester and smoked Camel Lights. For her, I came out. For her, I tried on a lot of terms and landed on "queer," because it defined who I was nicely, and I still use it today. She was a couple years older than me, so I expected her to be more put together than I was, but I didn’t understand the power the Catholic church had over people until later that year, when I watched Sinead rip up that photo of the pope live on Saturday Night Live.

Advertisement

This girlfriend was an ex-Catholic so deep in the closet and so full of internalized homophobia and shame that she lied to everyone about her new relationship. I didn’t know it then but later I found out that she’d given me a boy’s name and called me her boyfriend to her mother. All I knew then was that she could not have sex with me and I thought it was my fault. All I internalized then was that I had found the courage to come out and tell someone how I felt, and I had been rejected.

Sinéad was there. She understood me. I fell in love with her fiery blue eyes, her rage, her shame, her unapologetic resolve. Her voice captivated me, encapsulated me. Sinead knew pain. I listened to her music, especially "The Lion and The Cobra" and "I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got," and I made all her lyrics about my life. Late at night, I blasted the song, "Troy" until the walls vibrated and I sobbed and cried and sang along with those powerful lyrics, determined to rise like "a phoenix from the flames," with the courage Sinead had to kill any dragon that came my way.

Sinéad understood what it meant to feel spurned and to rise again because there is truth within you that burns bright and strong. That flame went out this week for Sinead and a little part of the sky went dark. Too young. Too soon.

But thanks to her rage and her persistence, I found mine.