Advertisement

Commentary

The cell phone turned 50 this year. To celebrate, I’d like to be a little less connected

I'm out for my daily walk on a wooded pathway not far from where I live. I’m enjoying the movement of my body through space, the sensation of air and sun on my skin, the light filtering through the network of leaves and branches above me. I’m thinking but not thinking. My mind is tetherless.

Then, at the height of this quasi-transcendent moment, a nagging thought about work creeps into my mind. I jam my fingers into my back pocket to haul out my cell phone. I check my phone.

I catch myself feeling microdoses of panic and anxiety — FOMO on my own life. What am I missing?

I read an email; I send a text. Of course, I’ve missed nothing important. The spell I had cast — of nature, of solitude, of temporary detachment from the looming outside world — is broken.

Such is the dark magic we humans have awakened. Cell phones are with us, always. I was once a late and grumpy adopter of the cell phone. I was the last among my peers to finally buy one and even when I did, it was a flip phone with no Internet access. I resisted the latest models, hanging onto my clunky iPhone until it self-imploded from obsolescence.

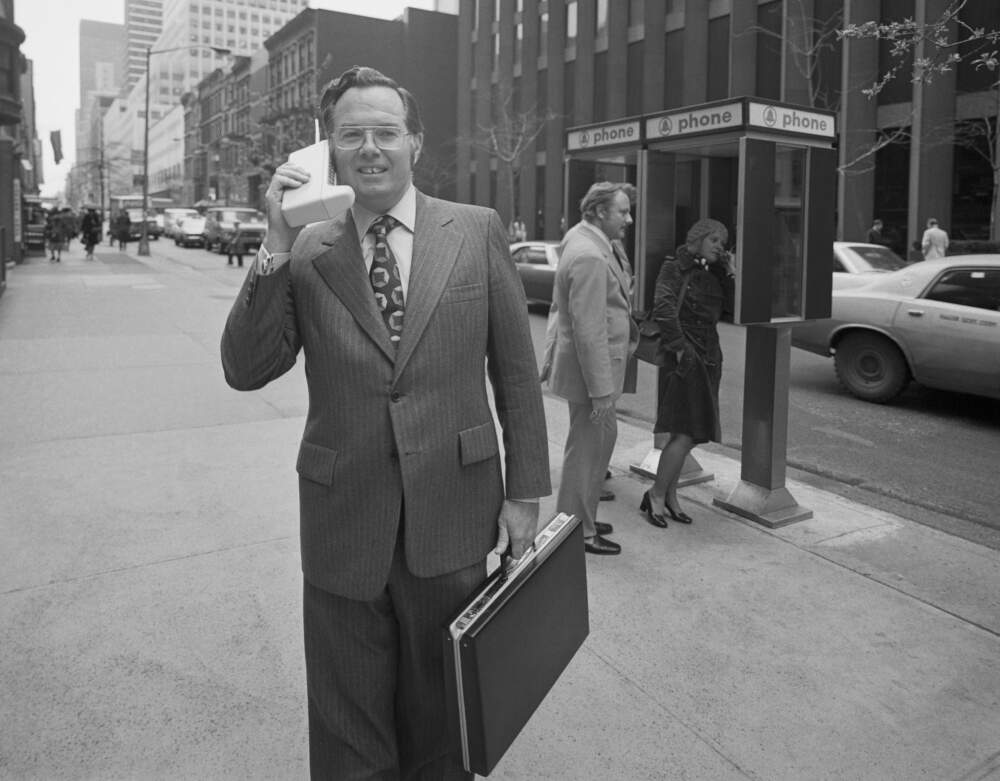

But, as Darth Vader once said, "It is useless to resist." All of us: About 97% of Americans own a cell phone, and 85% own a smartphone. I’ve been thinking about the scourge of the smartphone because, earlier this year, planet Earth “celebrated” the 50th anniversary of the first phone call made from a cellular phone. The milestone has made me think about what we have gained, but also lost, by agreeing to invite tiny, network-connected computers into our daily lives.

Yes, there are obvious benefits of being a text or FaceTime away: to reach someone during an emergency, whether dire and life-threatening (“Honey, the car broke down on the Mass Pike!”) or less so (“Honey, what kind of Keto granola am I supposed to pick up?”). And much has already been said about the smartphone’s penchant for sabotaging the art of conversation and "phubbing’s" drain on interpersonal relationships.

Even Martin Cooper, the Motorola engineer who essentially invented the cell phone in the early 1970s, has decried the loss of privacy his device, and the Internet at large, has wrought. “We don’t have any privacy anymore because everything about us is now recorded someplace and accessible to somebody who has enough intense desire to get it,” Cooper said recently at a telecom industry trade show where he received a lifetime award.

But Cooper’s privacy concerns have more to do with data, and how cell phones, as part of the Internet, capture and store personal information — shopping habits, our search history, our geographical location, plus whatever drunk selfies we willingly share with strangers via social media.

Advertisement

My privacy lament is more personal: What I most miss is being alone. My personal freedom from the Internet.

By freedom, I mean the need we all have for healthy isolation, for not being able to be reached, for solitude, unbothered by anything but our thoughts. Solitude is essential to problem-solving, emotional regulation and creativity. Without solitude, I cannot lose myself in nature, allow my brain to run deep and reflect, or recharge my metaphysical batteries. In the worst case of constant connection, we give up control of the rhythm of our lives.

"We dance to someone else's drum,” Nicholas Carr writes in the foreword to Michael Harris’s book “Solitude: In Pursuit of a Singular Life in a Crowded World.” "We’re in a crowd even when we’re by ourselves.”

Interrupted by our phones, we can’t hear when opportunity knocks. In a recent episode of "Ted Lasso," Rebecca falls into an Amsterdam canal and loses her phone — bummer! The upside: She meets a mysterious stranger and, because she can’t contact her friends, that meet-cute leads to romance.

It’s not surprising a proliferation of books have appeared about solitude and its dearth, ever since cell phones became ubiquitous. Apparently, liberation from our devices was never a future Cooper had in mind. “A cell phone ought to be an extension of a person, it ought to be with a person all the time,” Cooper recently suggested. His vision is for his clunky brick to eventually “become a part of you,” “embedded under your skin.” He believes we are “just at the beginning of the cell phone revolution." Yikes.

Our reachability used to be tethered by place. You had to call a landline in a physical location, screwed to the wall, lashed to a desk, the person and the place inextricably linked. You would try to "reach them at home" or "call the office." If you were home, you were expected to pick up. If not, you didn’t. “Phones used to belong to a household,” Ian Bogost wrote recently in The Atlantic. Landlines “emphasized the household as a unit, one with common interests.”

Today, only 27% of Americans still have landlines (and only 5% consider landlines their only or primary phone). With individual cell phone ownership, that sense of commonality is gone. Now we’ve extended that tether wherever we go. The cell phone is an invisible, tangled cord we drag behind us during our days. The unspoken social contract is that we must be available 24/7, without ever consenting to it. (I don’t recall signing that user agreement.) The downside is a constant state of vigilance.

The tragedy: We allow this intrusion, willingly, into our lives — the price we pay for omnipresent access and convenience.

Some days I just want to go for a walk, like when I was a teenager, aimlessly wandering after school. The only way anyone could reach me was if I decided to reach out to them, dropping a dime into a parking lot phone booth. As the old AT&T commercial used to say, "Reach out and touch someone." Sometimes I don't want to reach out or be touched. I want to be left alone.

One solution: I could make my smartphone “dumb,” or turn it off when I walk. But I doubt I'd have the willpower to follow through on that.

To be alone with ourselves and our thoughts must become an intentional act. So I have an even more radical idea: The next time I walk, I'll leave my device at home. Instead, I’ll bring myself.