Advertisement

Commentary

Rosalynn Carter helped me, and thousands of other Cambodian refugees, survive

I never got the chance to meet former first lady Rosalynn Carter in person, but our paths have crossed more than I could have imagined. I wouldn’t be in the U.S. today if it weren’t for Carter, nor would 150,000 other Cambodian refugees who resettled here after surviving the Khmer Rouge genocide that killed 2 million Cambodians.

In 1979, Carter first saw me. She saw me in the thousands of people who came in waves to the border of Thailand; injured, sick or dying Cambodians who fled the fall of the Khmer Rouge. It was five years before I was born, but her actions laid the groundwork for my family to find shelter, to have something to eat when we were hungry, or medicine when we were sick.

When the refugee border crisis first unfolded in 1979, international relief efforts were disorganized. Rampant corruption among military forces funneled aid straight into the pockets of foreign soldiers and commanders. The aid wasn’t getting to the people showing up on death’s door at the Thai border.

A world away, Carter watched images of the emaciated refugees, suffering from malnutrition and disease, on the evening news. She discussed the situation with her husband, President Jimmy Carter. They both recognized that government alone could not ease the problem.

“Judging from my mail and the telephone calls coming into the White House, I knew people were eager to help. But they didn’t know how,” wrote Carter, who died last month, in her memoir, "First Lady from Plains."

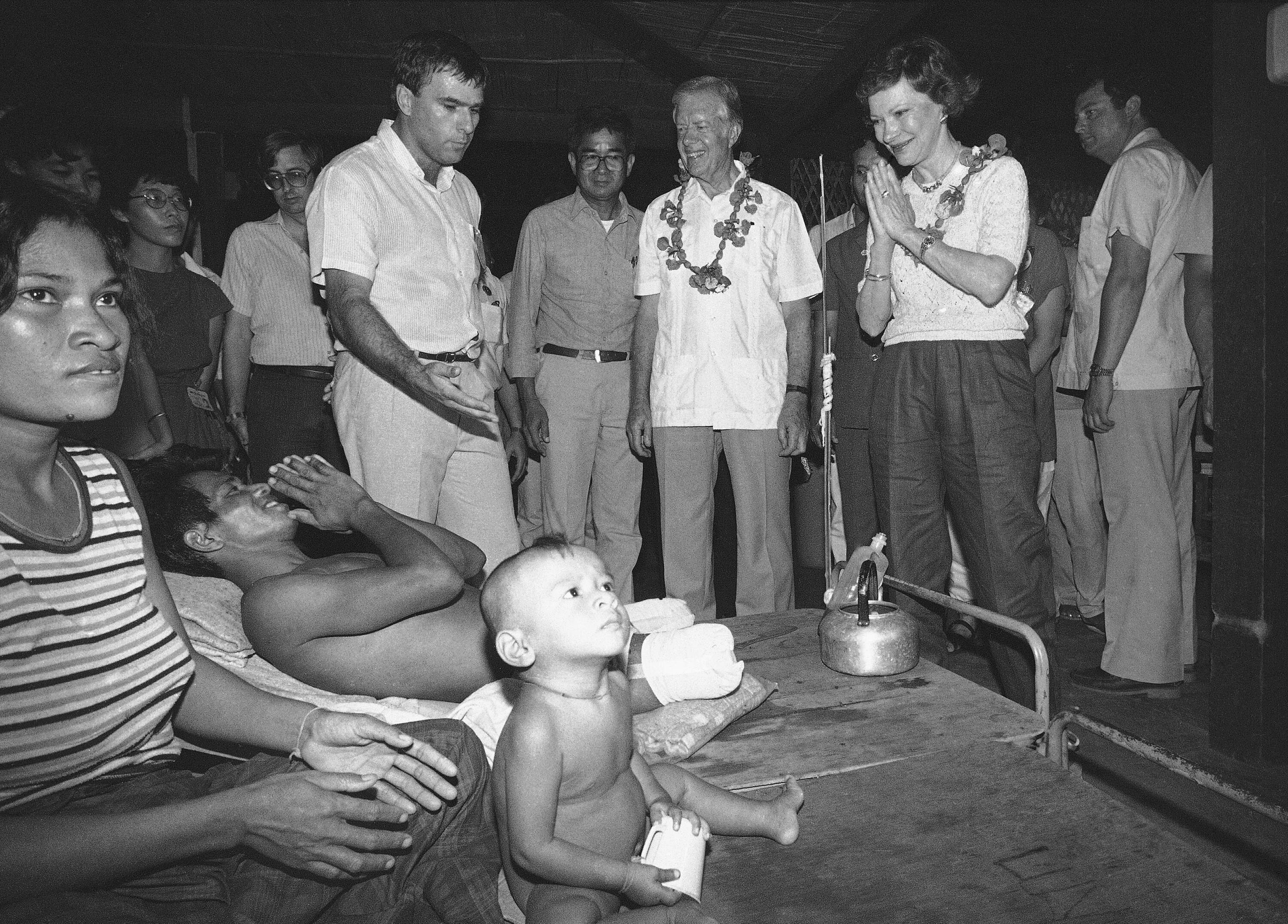

Members of the National Security Council’s staff suggested that she personally go to the refugee camps in Thailand to call attention to the need for help. It was the first time that a first lady would make a trip to Thailand — and in the middle of a war zone.

She arrived within days of the Sakeo Camp springing up along the Thai border. Nothing had prepared her for the amount of human suffering she witnessed when she arrived, she said.

“I thought about our country and how little we realize of the suffering and distress and grief in the world,” she wrote in her memoir.

She saw hundreds of children grouped under one tent, a mass of thin and frail bodies. But the most eerie part of all was the silence. No sounds of childhood, not even crying. Carter stood in the middle of one tent and cuddled a baby girl who was so weak, she didn’t have the strength to hold up her arms.

As she was leaving the camp, she heard a commotion. Someone came to tell her that the baby girl she held had just died.

That baby girl could have been me.

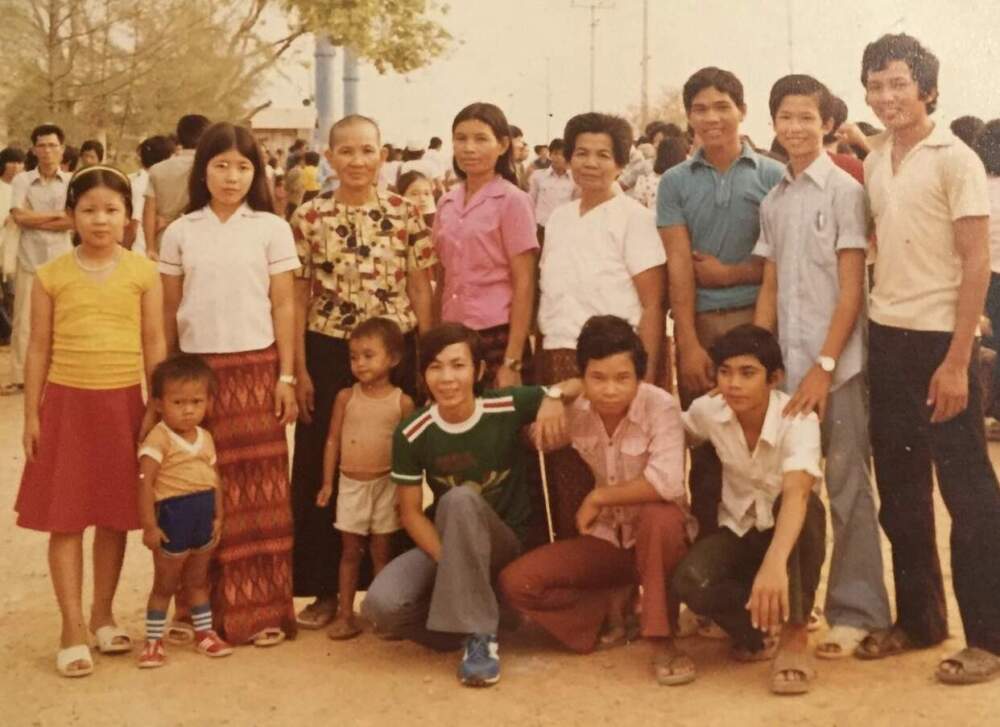

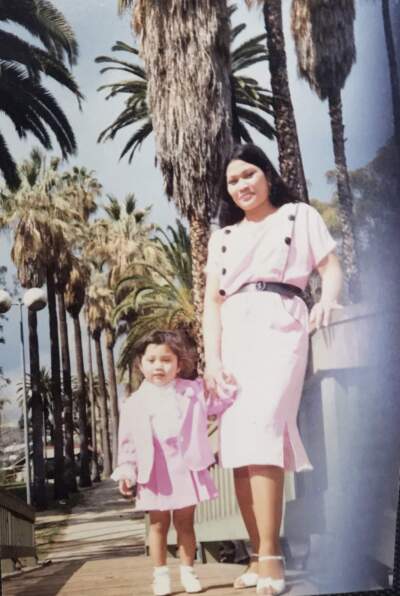

I was born five years later in 1984 at Khao-I-Dang camp, a main point of entry that allowed refugees to immigrate to another country. My family was fortunate to be there. Many refugees tried sneaking into Khao-I-Dang because they knew getting there was the only way out. Our family was sponsored by relatives to come to the U.S. in 1986. In the years that we waited for a chance to leave, we survived because of Rosalynn Carter.

She spent just 48 hours on the border, but the heartbreaking images were seared into her soul. She came back to the U.S. armed with information and a mission.

She convinced the secretary-general of the United Nations to name a U.N. coordinator for the relief effort. The advisors on the Thailand trip with her formed the committee that ran U.S. fundraising.

Advertisement

But the effort needed publicity. Carter became the voice of a national campaign that blasted television and radio airwaves with PSAs pleading for financial support for Southeast Asian refugees in the camps.

“It is almost impossible to describe the devastating conditions of the refugees from Cambodia. but I’ve seen for myself this human suffering,” she said. “I've held starving children in my arms.”

She also made speeches, national TV appearances, traveled to promote fund-raising programs and held luncheons and receptions in the White House.

The response was immediate and overwhelming. The American people rallied: major corporations, grass-roots campaigns, religious communities, politicians and laypeople alike.

The national campaign raised over $70 million in aid for refugees like me. The process she set in motion likely helped me survive the bouts of illness I had as a baby. It gave me enough food to eat to grow into a healthy toddler. At such a young age, I was immune to the suffering around me. My parents told me I exuded joy and confidence. I brought laughter and smiles in the midst of sorrow.

“When I think about her impact as First Lady, I think that the Cambodian refugee project was probably one of the most important things that she did,” Kathy Cade, one of Carter’s longest-serving aides, and her director of projects in the White House, told me.

Carter’s compassion paved the way for generations of Cambodian refugees who have resettled here in the U.S. We were given a chance to start fresh.

In 1989, three years after we arrived in Los Angeles, my parents opened their own business. They were embarking on what is now a 35-year journey of owning a donut shop. It’s a line of work that many other Cambodian refugees followed. They didn’t need a lot of education, just a willingness to get to work and provide for their families.

My parents’ drive to survive allowed me to focus on education, get a college degree and pursue my own career in multiple media and journalism ventures, including the latest that allowed my path to finally cross again with Carter.

I was working as a radio journalist at KVPR, the NPR affiliate in Fresno, California. My editor suggested that I apply for a fellowship with The Carter Center for a story I wanted to work on investigating the lingering effects of PTSD on Cambodian refugees who survived the Khmer Rouge genocide.

I was accepted, one of nine honored with the fellowship that year. For nearly 30 years it has provided more than 200 journalists the resources to report on mental health issues, a living monument to Carter’s passion for mental health advocacy.

It was during this fellowship that I first learned about her role in helping the Cambodian refugees who I was reporting on.

Earlier this year, I completed my project exploring the impacts of intergenerational trauma on the younger generation of Cambodian-Americans, completing the circle that Carter began 44 years ago when she first saw the images of refugees amassing at the border.

During my fellowship, I spent a lot of time corresponding with Kathy Cade, Mrs. Carter's director of special projects, who still regularly visited the Carters in Plains, Georgia. This story about Carter’s efforts to help refugees was something that stuck with her. When I first told her that I was one of the babies born in Khao-I-Dang, I could hear the surprise in her voice.

“I'm so happy that you survived,” she said after a long pause. “Because you know, lots of people did not.”

I got a chance to not only live, but to build a life that I’m proud of today. In 2022, an investigative story I worked on won a national Edward R. Murrow award, one of the highest honors in broadcast journalism. The magnitude of my journey was not lost on me.

It was Rosalynn Carter who cleared the path for me to get there in the first place. And it was Rosalynn Carter’s fellowship that opened the way for me to continue reporting on my community. My path had lead me right back to her.