Advertisement

Commentary

The gendered fault lines defining the 2024 election

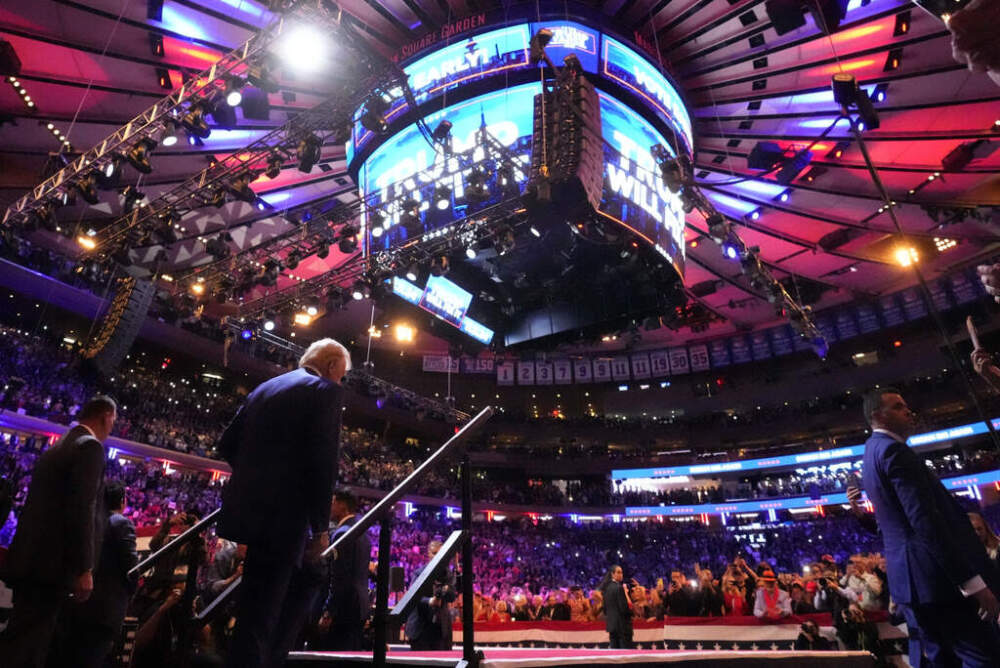

Donald Trump’s rally at Madison Square Garden Sunday night was an awful brew of xenophobia, racism and sexism that showcased our nation’s worst tendencies in the heart of its largest media market. The misogyny was palpable. One opening speaker joked about Taylor Swift being murdered by her boyfriend. Another compared Kamala Harris to a prostitute with “pimp handlers.” And, in an insult rooted in several tired tropes, Tucker Carlson called the vice president “low-IQ.”

The rally is the latest test of the American political media’s ability to cover an election featuring not just a female candidate but also an electorate with a massive (and growing) gender gap, where women overwhelmingly back Harris and men, especially those under 30, break for Trump. A few months ago, while Harris was still working the phones to shore up Democratic support for her White House bid, I argued that journalists should tackle head-on the role sexism and racism would play in her campaign.

The press has, for the most part, done just that, even as Harris downplayed her identities. Some examples: The Washington Post recently described the vulgar anti-Harris T-shirts for sale at Trump events. The Associated Press explored the role of hyper-masculinity in the GOP. The New York Times devoted an entire episode of its flagship podcast, The Daily, to “the gender election” and called Sunday’s rally a “carnival of grievances, misogyny and racism.” Although Trump did eventually talk policy at Madison Square Garden, most news outlets similarly (and smartly) led their coverage with the slurs and insults that pervaded the evening.

These vitriolic headlines are exhausting to read, but they reflect a welcome departure from the sexist media coverage that has plagued past election cycles in which politicians — much like voters and political journalists — were assumed to be white and male. As a result, women candidates have long been objectified, vilified or treated by the media as novelties instead of legitimate contenders. Women voters, meanwhile, have historically been portrayed as a special interest population with concerns that creep onto the front page only in election years. Because men’s experiences were the default, anything else was ignored, minimized or discussed in only the vaguest of terms.

Things are different this time around for several reasons. The increase in women politicians and women journalists has certainly helped, and the aftershocks of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss to Trump launched a widespread (and still unfinished) reckoning with misogyny. Another significant factor, though, is the 2017 resurgence of the #MeToo movement, which was spurred by investigations from The New York Times and The New Yorker into accusations of sexual misconduct by movie mogul Harvey Weinstein. These stories raised awareness, unleashed a tidal wave of accountability and finally resulted in punitive consequences for many powerful men who preyed on women.

This movement led many U.S. newsrooms to create “gender beats” to cover reproductive justice, sexual violence, caregiving, workplace sexism and other issues historically deemed beyond the bounds of serious news. As I learned when I studied this phenomenon in 2020, the journalists working these beats infused their newsrooms with a new type of expertise and shifted news judgment in ways that appear to be influencing political journalism in this election cycle.

Advertisement

Women across the political spectrum are receiving serious coverage as candidates, power brokers and voters. Journalists are talking about men as a distinct voting bloc and exploring the roots of their discontent. There’s more nuanced, albeit still imperfect, attention paid to the queer community. Abortion is being framed as a matter of public health and an often-complex personal choice, not a shameful secret. All in all, the political press of 2024 is closer than ever before to portraying women’s experiences as American experiences that reverberate across the electorate and throughout the halls of power.

There is some poetic justice in the #MeToo movement having prepared news organizations to better cover a presidential election pitting a powerful woman against a man accused multiple times of sexual misconduct. And, yet this election cycle also lays bare the backlash that so often follows efforts to correct injustice.

The rally at the Garden was a high-profile example. There are other signs, too. The sexist rhetoric from the right continues to intensify not just at campaign events but in political ads like one from Elon Musk’s PAC that calls Harris “the c-word.” (The ad eventually clarifies that it’s talking about communism, but it also includes multiple nods to that other term.) Young men, who are rightly frustrated with their prospects, are being offered a lifeline by Trump that requires them to embrace, or at least tolerate, masculinity laced with crude aggression. We are, if the polls are correct, a coin toss away from electing an administration likely to further restrict reproductive choice, promote dangerous anti-trans rhetoric and policy, and act as if prosperity for men must come at the expense of opportunity for others.

The race seems far too close — and this year has been far too bizarre — to make any predictions about what will happen come Election Day. The gendered fault lines that divide us are, however, clearly drawn in part because the news media has done a good job illuminating them. We’re choosing not just the next president, but also signaling how our society will empower or repress different genders in the years to come. Only time will tell what force will win: the reckoning or the backlash.

Follow Cognoscenti on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our weekly newsletter.