Advertisement

Commentary

There's refuge to be found in 'snags'

Lately, on my walks in the woods, I’ve been drawn to trees that are dead but still rooted. At first, I saw them as deadwood and wondered why the park service hadn’t cleared them away. The more time I spent wondering about them, the more fascinated I became with their textures, their shapes, their beauty. My curiosity led to some light research where I discovered that these dead trees are called “snags.” They provide hiding places, foraging spots, perching and nesting sites for various wildlife.

Up until now, the only definition of snag I have known carries negative connotations: literally, something sharp or jagged. Figuratively, some sort of obstacle: a delayed plane flight, unexpected traffic, a rejection I was sure would be an acceptance, an election that did not go my way.

I’ve only ever thought of snags as negative. But with this new definition, I have reason to see them as positive, as places of refuge, as places where woodpeckers find insects, where groundhogs and squirrels make dens, where deer may hide. Perhaps one of the most famous snags is in Big Bear Valley in San Bernardino County, California, where Shadow and Jackie, the eagles on a webcam, keep their nest atop a tall, dead pine tree that has been dubbed “Stick Depot Snag.”

Learning more about snags in nature calmed me somehow. How had I ever thought these leafless trees, these trunks and stumps should be cleared away? They welcome raccoons and bats and mice and owls into their hollows. Time has changed them, aged them into weathered wood with cracks and crevices. Yet, they provide haven and feed the hungry. The sun shines on their bark. They stand naked in the cold. Some with lost limbs. Some misshapen. In their dying, they make homes for others. They have roots. They provide roots. They belong right where they are.

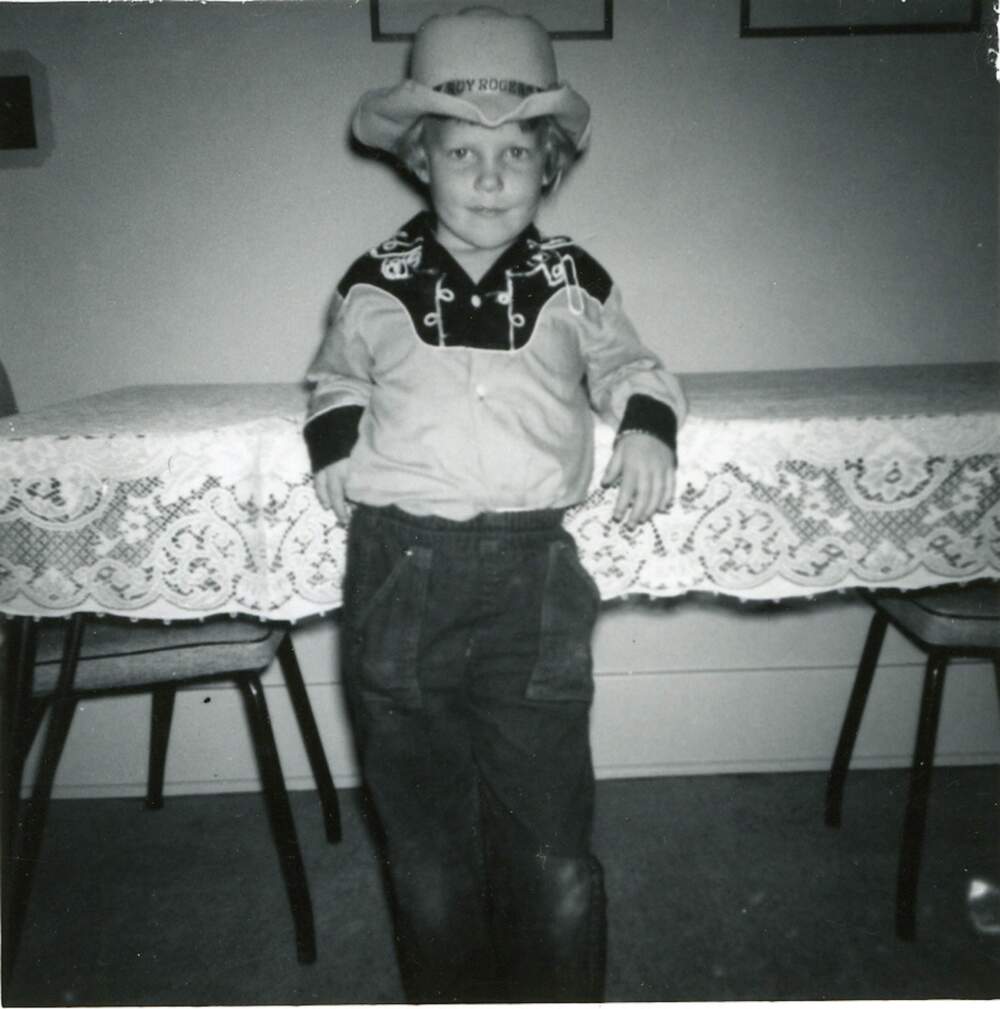

And perhaps the snags have something to teach me about belonging. Throughout my childhood and into my adult years, I carried an aching need to belong. I didn’t fit in. I was uprooted over and over again and had no sense of home. As a girl growing up in places like Louisiana, Wyoming, Texas and Colorado during the 1960s and ‘70s, I never saw any signs of queerness. In New York City and San Francisco, there were communities of acceptance, but I was too young and too isolated to know about them. It wasn’t until my 20s, when I experienced suicidal thoughts, a breakdown and hospitalization, that I even came out to myself.

What a strange and scary experience it is to be inside a queer body without any reference points, without any mentors or models to follow. Coming out to others, in a way, was much easier than coming out to myself. In high school, I had friends, but I was always on the margins — a spectator to their seeming ease with social constructs. I had no way of identifying my difference. I didn’t have the vocabulary.

Advertisement

In my English textbook, I came upon a poem by Langston Hughes called “Impasse.”

I could tell you

If I wanted to

What makes me

What I am.But I don’t

Really want to

And you don’t

Give a damn.

The poem, I guess, was a sort of snag. It gave me a place to stop and rest. It spoke to my sense of being different and misunderstood. Of course, I still didn’t know what I was or how to explain it, but somehow, Hughes’ poem helped me recognize my own impasse — my inability to identify who or what I was. I copied “Impasse” into the journal that my English teacher, Mr. Bennett, required. On other pages, I attempted my own poems —awkward rhymes about my loneliness.

Mr. Bennett, who wore colorful shirts tucked into bell bottoms, who had dark sideburns that met at the edges of his mustache, was helping me find my voice, giving me a place to belong in the pages of that journal. Langston Hughes was, too.

Another teacher, Miss Linen, taught Shakespeare. She was old, at least to my young eyes. And all the kids were afraid of her. When she told us to memorize a passage and stand in front of the class to recite it, I chose Macbeth’s “Tomorrow” speech. It has many beautiful lines, but two of my favorites are: “And all our yesterdays have lighted fools / The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!”

Miss Linen helped me understand poetry, the cadence and language of Shakespeare. After class one day, I asked if she would read one of my own poems, and she did, pointing out a spot where I made a metaphor and telling me, “Do more of that.” I do not recall the poem or the metaphor, but I am certain my writing was young and clichéd. She could have been critical, pointing out the flaws; instead, she found a teaching moment, a moment of praise, that gave me direction and helped me understand an important literary concept. My fear of Miss Linen disappeared.

Mr. Bennett, Miss Linen, Langston Hughes and Shakespeare were snags in the forest for me. They were my hiding places and foraging spots. They pointed me toward home.

I became an English teacher, and I often read “Impasse” to my first- and second-year college students. I also require them to memorize and recite poems, as Miss Linen did.

Now, years away from that lost girl, I have more resources and a sense of community. More places to find comfort and shelter. In the 1960s and '70s, I could never have imagined the queer friends and allies I have now. I could never have imagined meeting the love of my life, being 30 years together and counting, being present for and a participant in history-making marriage equality, and being completely out of the closet.

Even so, I still sometimes hit figurative snags, those moments when “what makes me what I am” gets questioned in the public arena, when difference of any kind becomes dangerous. In those moments, I need to remind myself of the other kind of snags, the ones that provide homes and nourishment to those who seek refuge.

Poetry, stories, music, and art bring me that refuge. I remind my students that they can find meaning —and refuge — there, too.

Follow Cognoscenti on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our weekly newsletter.