Advertisement

Commentary

'Hidden in Plain Sight': The forgotten history of the Holocaust in Serbia

Editor's note: I remember the first essay Julie Brill wrote for Cog. It was an early draft of a story she tells in her new memoir, “Hidden in Plain Sight: A Family Memoir and the Untold Story of the Holocaust in Serbia,” about a trip she took with her father, Haim, to Belgrade, Serbia’s capital.

When Haim was just 3 years old, his father, Alexander, was murdered by the Nazis. He had been imprisoned at Topovske Supe, a concentration camp located on the outskirts of Belgrade (operational from August to December 1941), then executed by firing squad and buried in a mass grave with thousands of other Yugoslavian Jews.

The premise of Brill’s essay was that she couldn’t remember the name of the camp where her grandfather had been imprisoned, and how few people at all would be able to recall it. “The Holocaust in Serbia is so little discussed, even most Holocaust experts haven’t learned its name,” Brill explains. “As a child, I knew my grandfather was a victim of the Holocaust, but also thought somehow that the Holocaust had not really come to Yugoslavia, because nobody talked about it.”

The haziness around what happened to her family, sent Brill on a decades-long quest for understanding. She wanted to make some sense of the stories her father told her about his childhood, and the lessons she learned about the Holocaust in Hebrew school.

I happened to read an advanced copy of Brill’s memoir days after encountering Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s extraordinary essay about the Holocaust in the New York Times Magazine. That essay is many things — commentary, personal reflection, history lesson — but it also surfaced some startling statistics. First, the median age of the 220,000 Holocaust survivors today is 87, inching us ever-closer to a post-survivor era, where the children and grandchildren of survivors will be vessels for their stories; “15% of American adults under 30 believe the number of Jews murdered in the Holocaust is ‘greatly exaggerated;’” and 48% of all Americans surveyed could not name even one Nazi concentration camp or ghetto.

I don’t know how any of this can be. How are so many confused or misinformed or in out-right denial about the horrors of Holocaust? Yet, they are. It what makes Brill’s memoir such an urgent and important read. -- Cloe Axelson

“On the Four Photos”

When I was growing up, my dad had four black-and-white photographs from Serbia. A camera was a luxury in interwar Belgrade and it’s unlikely that my grandparents owned one. Instead, portraits were taken by professionals who would shoot in public places and then hand out their cards so the subjects could return to their shops another day to purchase the developed pictures. The precious images somehow survived the war.

My parents kept the photos casually tucked away in an envelope in a drawer with other papers. Periodically, my mother would be looking for something, and they would surface and get passed around. I felt every time she was surprised to find them; their importance as a window into a world I would never see was belied by where they were kept. My parents, my younger brother Alex, and I would all look, holding them by their yellowed, curling edges so as not to mar them with our fingerprints. No picture frame or album protected them.

One photo was my paternal grandparents’ formal wedding portrait, taken in interwar Belgrade. I knew nothing about their wedding: not the date, not who was there, not what the wedding was like, or if there was a honeymoon. Alexander Brill, nicknamed Aci, and Regina Francezi, known as Delpha, posed, elegant and young. My grandfather has removed one white glove to hold my grandmother’s arm with his bare hand. From a white cap that sits on top of her short dark hair, a veil flows down my grandmother’s back and pools on the floor behind her. She was stunning in her long silk dress.

During the war, she will cut up its train to make clothes for her children.

I studied the faces of these grandparents who were strangers to me. Like all brides and bridegrooms, they stand together, ready for an unknown future —for better or worse. I tried to imagine what their lives were like, what they were like, from the crumbs I could gather. They were established in Belgrade where they had been their whole lives. Where their families were. Where likely they expected to live and die.

Advertisement

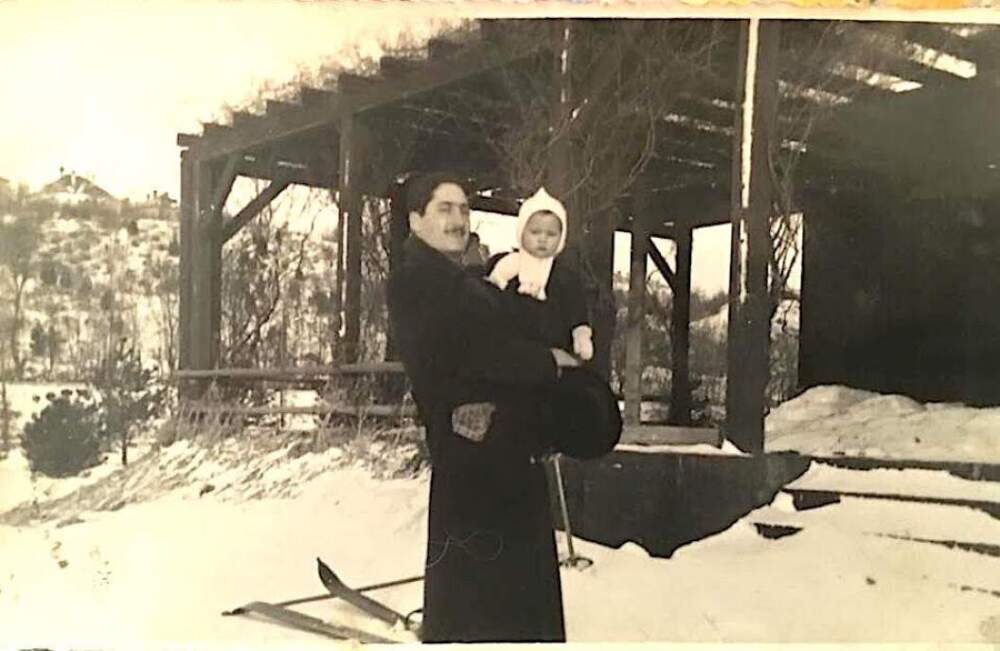

My father’s second picture was taken in the winter of 1938-39, after Kristallnacht in Germany. Translated as the Night of Broken Glass, the pogroms destroyed thousands of Jewish stores, buildings, and synagogues. Attackers, often neighbors, injured and killed Jews who they frequently knew by face, if not by name.

In the image, my father is a round, rosy-cheeked baby, well-bundled against the snowy Serbian winter. Did my grandmother knit his hat and mittens? My grandfather held the baby against his long, dark coat. He had dark hair, a mustache, fine features, and a satisfied expression. This young father looked so proud of his firstborn. When this image was captured, did he envision a future with albums and frames filled with photos of him with his growing son and the other children he likely expected to follow?

In the background, a pair of wooden skis rest beside an open-air structure. It looks as if they are on vacation. An optimistic image that doesn’t foreshadow the coming World War. Visual proof my father had a father and that there was a prewar period when everything was in order, though he doesn’t remember the man or the time.

My dad and his mother posed on a park bench in a third picture. It’s probably an ordinary day in the last months of prewar Yugoslavia. Because the image survives, so does the moment, representative of many that are lost. Photographs were more valuable when people had to pay for film and developing.

My grandmother was slender and stylish in a short-sleeved, polka-dot blouse and short solid skirt, one ankle crossed over the other. My father wore a collared shirt with broad horizontal stripes, shorts with suspenders, and leather shoes with white socks. He half stood on the bench, half sat on its back, while my grandmother secured him with one hand behind, the other on his bare knee. I studied it, looking for clues, signs of my father in the little boy’s face.

They gazed at the photographer. Their faces were close but not touching. The family resemblance is striking; they had the same eyes, the same nose, their hair is parted in the same spot. Did my grandmother see and appreciate their similarities? She gave a slight smile, but the little boy who will become my father is somber. Next to him is a toy metal pail with Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; American culture has somehow found its way to the Balkans.

And then there is the photo I could never understand. My dad and his little sister stood on a city street during the German occupation. In the black-and- white image, my aunt wore a light summer dress she told me her mother sewed, her legs bare, with short socks and leather shoes. My dad must have been five or six. He wore short pants with suspenders, knee socks, and laced leather boots. This image clashed with my understanding of that period, gathered from reading survivor accounts of the Holocaust from the tiny temple library during my pre-adolescent Hebrew school years. These children are not hiding.

This essay was excerpted from Julie Brill's new memoir, "Hidden in Plain Sight: A Family Memoir and the Untold Story of the Holocaust in Serbia." To learn more about the book or attend an upcoming event, click here.

Follow Cog on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our newsletter, sent on Sundays. We share stories that remind you we're all part of something bigger.