Advertisement

Under The Microscope, A Pathologist Sees Beauty — And Danger

By Dr. Michael Misialek

Guest contributor

It was a typical busy morning. A flurry of people in and out of my office along with a growing stack of slides. I picked up the next slide, a pap smear.

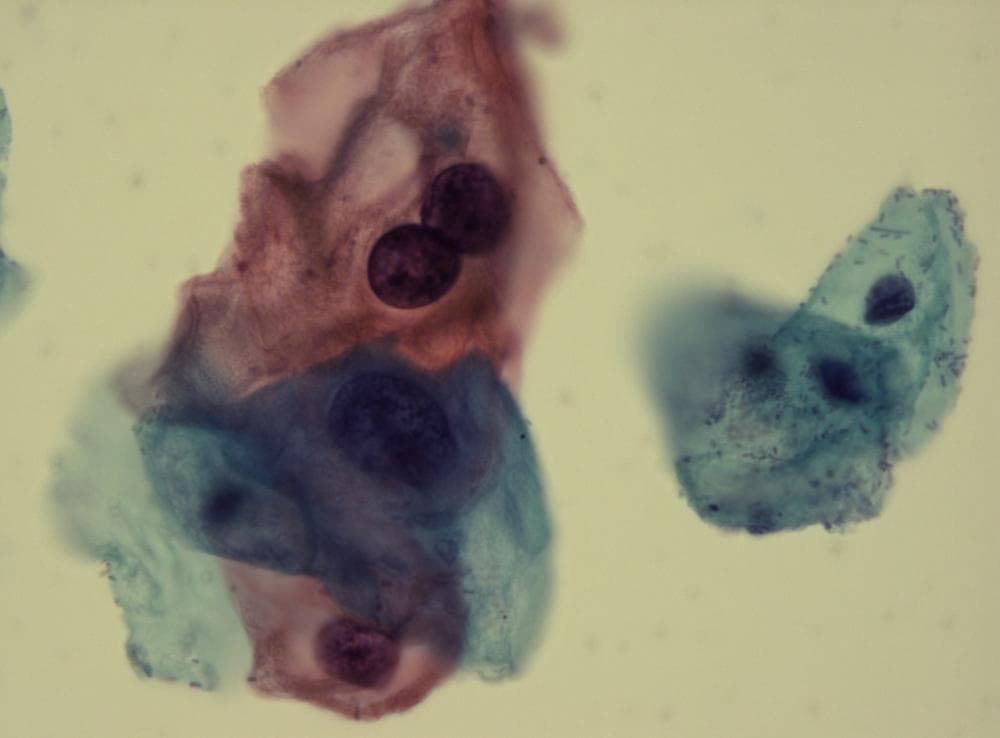

The requisition stated “24 yo, routine pap.” She had no prior history of any abnormalities. As I studied the slide, the normal cervical cells sparkled in shades of blue and pink. Together with their small uniform nuclei, this created an evenness to the slide, like a calm pond.

But off to one side, a cluster of dark and enlarged cells floated like sinister water lilies. I diagnosed “low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion,” a precursor to cervical cancer and a result of HPV, human papillomavirus.

Have you ever studied one of Monet’s masterpieces? The flowing movement of the lines, the broad pastel brushstrokes in the early evening sky, all drawing the viewer into a world of serenity.

Looking at this painting with a more critical eye, you can pick out the faint lemony yellow dots on the floating water lilies creating that effect of illumination. You notice the different colors of blues and greens that were used to create the depth of the water. All of these fine details emerge only upon closer examination, not upon first glance.

In my work as a pathologist, I frequently think about the beauty under my microscope, never failing to be amazed by the seemingly endless combinations of colors and cells that define my diagnoses.

We pathologists might be considered Monets in our own right. We are connoisseurs of the fine art that is your living tissue on our slides. Under our microscopes, the cells burst into vibrant hues of red, blue, yellow and pink, producing a rainbow of colors.

On initial examination, this is the impression that is created, but as we study the cells further, a new piece of artwork with much finer detail is revealed. The cells can gel together like the desert sands or flow in harmony like a running river. What lurks beneath that art can sometimes be a beautiful disaster, like a Jackson Pollock drip painting.

Art and science, typically on different sides of the brain, have never fit together so well, I think. A pathologist combines these two worlds — the visual aesthetic, and the hard medical information it denotes. I was taught in medical school to think of horses when hearing hoof beats — the simplest diagnoses will probably prove correct — but not to forget the zebras. As a pathologist, I look for the zebras in the herd. Among thousands of cells we are trained to find the one abnormal.

On that 24-year-old's pap smear sample, I homed in on that group of big dark cells. As I focused in, I quickly recognized this painting: these were koilocytes, the diagnostic cells of an HPV infected cervical cell.

Exotic cells can be exciting for us, but devastating for the patient. They can mean that these patients have become outliers. Nobody should want to be too interesting or exotic in the world of pathology and medicine. We want patients to stay inside the boundaries.

“This is a great case…a really interesting case,” is a common phrase heard when the truly unusual or rarely seen painting is uncovered.

There are three ways these come to light. The first is the uncommon presentation of a common disease. Imagine seeing a Picasso. Recognizable, but not until closer inspection does one start to see a nose, mouth, eyes, and begin to appreciate a woman’s face. Similarly in medicine, the seemingly unrelated and random muscle weakness, neurologic symptoms and hypercalcemia that come together in a diagnosis of lung cancer.

The second is the rare disease. Think about your first impression when seeing the works of an unknown artist. Your inquisitive eye is drawn into the world the artist has created. For me, encountering a new disease process under the microscope is like seeing a beautiful painting for the first time. The rapidly dividing small dark blue cells coming together in rosettes that lead me down the path of ... a rare neuroendocrine tumor.

The final, and perhaps most rare and intriguing is the atypical presentation of a rare disease. This is the contemporary artist whose work is difficult to understand but is still art nonetheless. A lot of time is spent under the microscope with these cases. Here I turn to my “palette” of special stains to turn the undifferentiated and difficult-to-describe cells into a defined tumor category. From there I can “paint” the cells further with even more esoteric molecular tests, in essence teasing out the secrets of its DNA. Out of this, a masterpiece under the microscope is created — a rare synovial sarcoma.

In medical school, we learn about the order in the human body. Pathology teaches about the disorder. Cells come together in a synchronized harmony where there is beauty in both the resulting normal function of organs and the chaos of disease.

Using our pigments — known as the Papanicolaou, hematoxylin and eosin, or Diff-Quik stains — a painting is created, whether an HPV infection, a cancerous cell or other disease.

But I never get too enchanted by this piece of art; I remember the patient behind the slide, the face behind the cells, like turning over the painting to see the artist’s signature and a dedication to a loved one. It suddenly becomes personal. Those diseased cells have now triggered a cascade of events about to unfold...worry, appointments, waiting, biopsies, operations. Sometimes death.

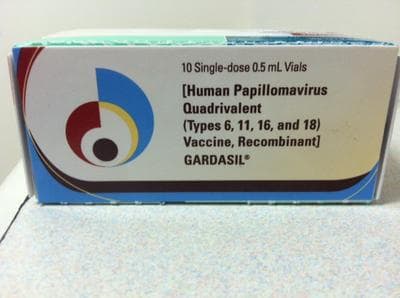

As I finalized the report on this case, yet another HPV lesion found in a pap smear, I thought: It doesn’t have to be this way. Every day, more diagnoses of HPV. It has no age, race or class barriers.

Earlier this year, the Annual Report to the Nation on the State of Cancer reported a drop in overall cancer death rates. However, incidence rates are increasing for HPV associated oropharyngeal and anal cancers. Vaccination rates against HPV remain low in adolescent girls. The CDC reports only about a half of girls received one or more doses of the vaccine. Only about one-third of girls and fewer boys have received the full three doses.

The medical community has not been effective in educating the public or even our fellow colleagues about the importance of the HPV vaccine. Pathologists diagnose HPV related diseases. Wouldn’t it seem natural that pathologists could help in this endeavor?

So let me say to you now: I wish you could look through my microscope for a day. HPV is beautiful and it is also hideous in the damage it can cause, but mainly, it is very, very real. And if it afflicts you or your loved one or your patient, you will not find it beautiful at all.

Dr. Michael Misialek is Associate Chair of Pathology at Newton-Wellesley Hospital and Assistant Clinical Professor of Pathology at Tufts University School of Medicine. Don't miss his previous post on "The Unseen Pathologist: Why You Might Want To Meet Yours."

This program aired on September 12, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.