Advertisement

Are Young Women With Cancer In One Breast Needlessly Having The Other Removed?

Are young patients with cancer in one breast, driven by unfounded fears and anxiety, having the other breast removed unnecessarily?

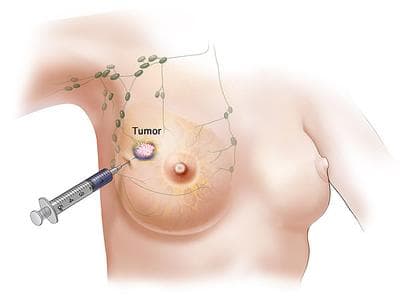

That's the troubling question implicit in this new survey of women 40 or younger who chose to undergo double mastectomies even though their cancer was only in one breast. The procedure, called contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM), has increased "dramatically" in recent years, particularly among younger women, researchers report.

But evidence suggests that the removal of a healthy breast in a woman with cancer in only one breast does not improve survival rates.

Still, researchers from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and colleagues report that more and more young women with breast cancer are electing to remove their healthy breast to "avoid recurrence and improve survival."

Specifically, the study found that among 123 women surveyed, 98 percent said they chose CPM to avoid getting cancer in the other breast and 94 percent said they did it to improve survival. (Also of note, 95 percent said they did it for a more nebulous but emotionally potent reason: "peace of mind.")

If you've had breast cancer, or know anyone who has, it's easy to see why such a subjective, non-data point like "peace of mind" might trump a more rational, just-the-facts approach to treatment. But this paper, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, points to what it calls the "cognitive dissonance" between what women know to be the facts and what they actually do.

"Many women overestimate their risk for actual cancer in the unaffected breast," the paper says, concluding that: "Interventions aimed at improving risk communication in an effort to promote evidence-based decision making is warranted."

More background from the Dana-Farber news release:

The purpose of the survey was to better understand how women approach the decision to have CPM. The survey included questions about the women's health history, reason for choosing CPM, and knowledge and perceptions about breast cancer. Most of the women had stage I or stage II breast cancer and 60 percent of tumors were estrogen receptor-positive. Almost all of the women surveyed indicated that desires to decrease their risk for contralateral breast cancer (CBC) prompted their decision to remove the healthy breast. Although 94 percent of the women surveyed said they chose bilateral mastectomy to increase survival, only 18 percent reported thinking that CPM improved survival rates. Almost all of the women surveyed overestimated the actual risk of CBC. While physicians were identified as the most important sources of information about breast cancer, only one-third of the women cited a desire to follow a physician's recommendations as an extremely or very important factor in their decision.

So why the disconnect?

Dana-Farber researcher, Shoshana M. Rosenberg, the lead author of the study, said in an interview that, of course, risk perception is complex and personal and that each cancer patient is unique

Still, she said, better communication between doctors and these patients may be warranted. "Assuming most docs are telling women about their relatively low risk of contralateral breast cancer, there would seem to be room for improving how risk is communicated," Rosenberg said. (Researchers estimate that the chance of developing cancer in the second breast is around 2-4 percent over five years.)

But this may not be a communication problem at all, says Sharon Bober, a consulting psychologist for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Program for Young Women with Breast Cancer (and also director of the DCFI's Sexual Health Program).

"It may be that this isn't about risk communication — it may be about how people make meaning out of numbers," Bober said. "These are women who feel they've been struck by lightening once [because they're young and got cancer] and they say, 'Why should I believe that lightning won't strike again? No one can say there's a 100 percent chance you won't get it in the other breast."

For some women, Bober says, any risk is too much risk. And when it comes to life-threatening cancer, the pervasive culture tells us that doing more is often better.

“In general, the broader cultural and medical context continues to amplify the message that more treatment is better,” Bober says, adding that women raise other reasons in favor of CPM, including the desire for a more symmetrical result from breast reconstruction. But more often it's just that deep feeling of wanting to do anything — everything — possible to avoid any further cancer, and eliminating any reminder of a future cancer risk; it's that impulse to simply take-them-both-off-and-be-done-with-it.

On the survey findings, Bober says: "Do we look at that and say, 'That's a shame because it was unnecessary?" Or do we say, ‘They needed to do that for peace of mind, and that’s okay — even if it’s not based on actual risk.' Especially with a cancer diagnosis, you want the feeling of moving forward...like you're making a proactive, empowered decision. It's really hard when you've had something happen to you that's rare, and powerful and scary. That becomes your evidence that something very unlikely can happen, because it has happened. It's hard to budge somebody in that case."

(An aside here to note a few limitations of the study. First, it's a survey of cancer patients conducted two years after these decisions were made, which means the imprecision of memory may also be mixed with an overlay of psychological re-interpretation that might have skewed the answers. Also, researchers didn't ask the women what they were told specifically about their level of risk by doctors, nor were the physicians surveyed. Another relevant point: Most of the women in the survey did not have the BRCA gene, which greatly increases their risk of developing cancer; among women who did carry the gene — about 25% of those surveyed — they did not overestimate their cancer risk, according to the report.)

Rosenberg, the lead study author responds:

We are not concluding from this study that's it's all about misperceiving risk, however it's a part of it, together with overestimating the benefit of the procedure since so many women said they chose CPM to improve survival/prevent breast cancer from spreading. We think this suggests that in many cases the decision is being made in a setting of anxiety, and the underlying fear of recurrence is driving a decision that will not affect the risk of developing a distant recurrence or of death from breast cancer.

Even though women might feel as if they are more in control of the situation and feel like they've “done everything possible” by having CPM , it's important to understand that their decision about surgery will not affect survival outcomes...

The takeway is that risks and benefits of surgery are not being optimally communicated and that some women have inaccurate perceptions about breast cancer that (together with anxiety/fears/concerns that are under-addressed when women are making decisions about surgery) might be influencing their choice of surgery.

The survey was a first step. We plan to delve more deeply into some of these issues with future qualitative work (e.g., focus groups with women who had all types of surgery, not just CPM, with the opportunity to ask the women directly about the decision-making experience; interviews with physicians about how they perceive the decision process).

Readers, breast cancer patients, what was your experience? Did your impulse to do anything and everything trump your true perception of your future cancer risk? Tell us, please.

This program aired on September 24, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.