Advertisement

Mass. Men Hit Particularly Hard By Opioid Crisis, New Data Show

ResumeThe opioid crisis in Massachusetts is hitting men particularly hard.

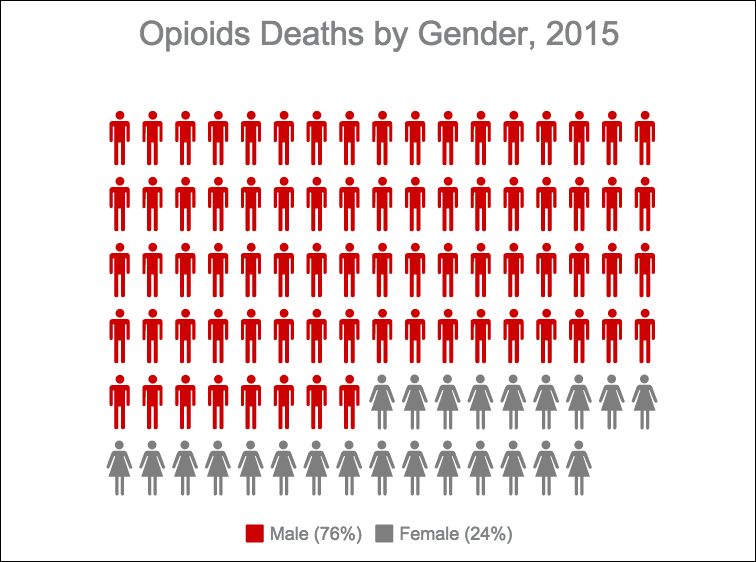

Over the first nine months of 2015, 76 percent of the confirmed overdose deaths in the state were men, according to the latest quarterly opioid snapshot from the Department of Public Health.

From January through September of last year, 604 men died of opioid-related overdoses, compared with 187 women who overdosed and died over the same period, the department said.

Wednesday's snapshot is the first time the state has released demographic data on the crisis.

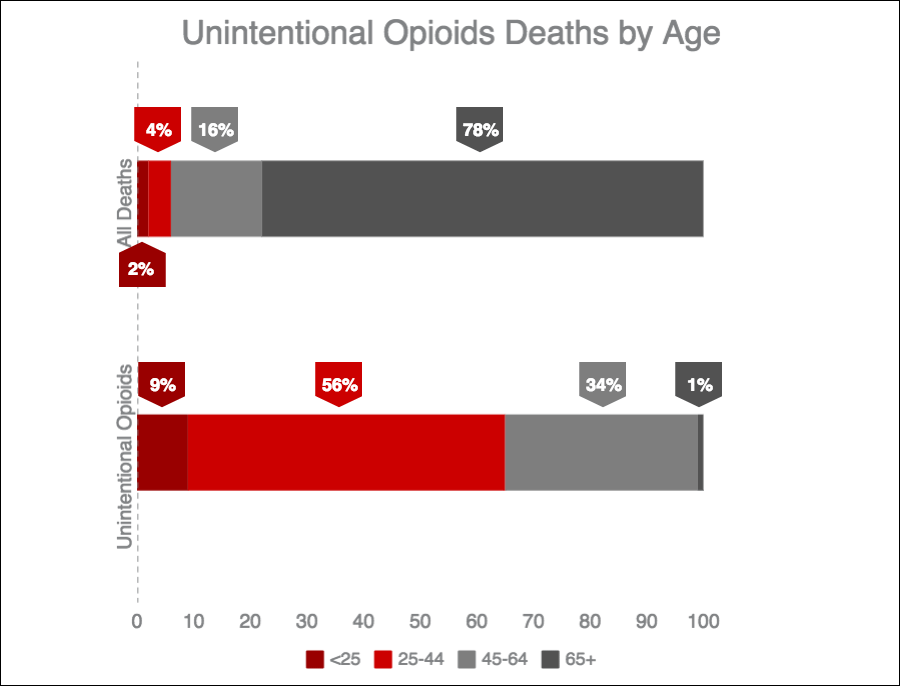

Of the 791 confirmed opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts over the first nine months of 2015, 81 were 15- to 24-year-olds, 247 were 25- to 34-year-olds, 203 were 35- to 44-year-olds, 178 were 45- to 54-year-olds and 82 were above 55 years old.

About 83 percent of all opioid-related overdose deaths over the first three quarters of 2015 were white non-Hispanic victims; 90 percent of all deaths in the state over that period were white.

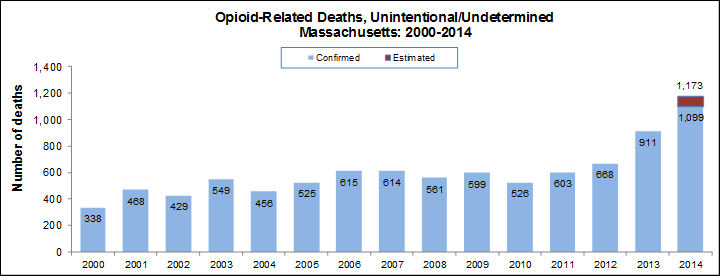

The snapshot also revised down slightly the total number of overdose deaths (confirmed cases, plus estimated data) in 2014, from a previous tally of 1,256 to a revised estimate of 1,173.

But that new revision includes 1,099 confirmed overdose deaths in 2014, which represents a 21 percent increase over 2013 — and a 65 percent increase over 2012 figures.

Social Contagion

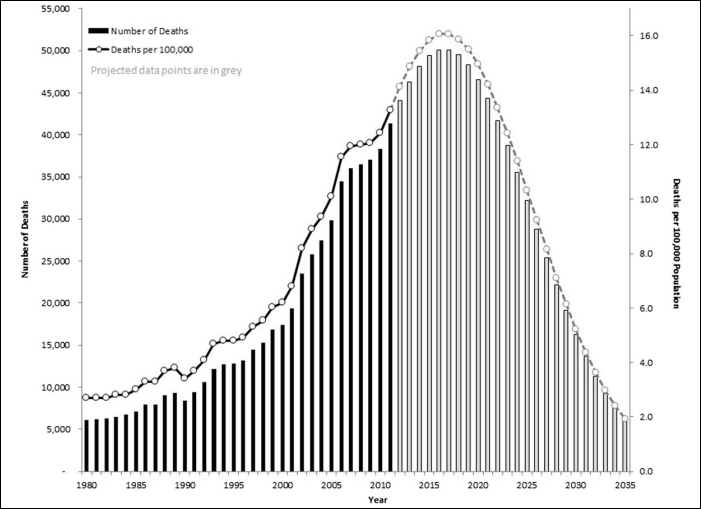

As deaths from opioids continue to rise in Massachusetts on a yearly basis, many people wonder: When will this end, or at least plateau and begin to decline? The state isn’t making a public prediction. The only published forecast I could find has the epidemic peaking in 2017 and 2018.

"Before then we would experience a continuing rise," said Gouhua Li, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health.

Some epidemiologists question Li’s forecast because it uses a prediction model for infectious disease epidemics like smallpox or HIV. A heroin overdose is not contagious; there’s no mosquito transporting a parasite or exchange of body fluid that leads to death.

But there is this theory called social contagion, which Dr. Li says applies to the opioid epidemic.

The opioid epidemic "spreads through social interactions, mostly," Li said. The exchange between a heroin user and their dealer would be an example. "[The dealers] make the drug available in the vulnerable population," Li said.

'Ridiculously Easy' To Get Heroin

Doctors have also come under fire for helping spread the epidemic — by prescribing too many opioids. So far, most of the effort to stop the spread has been focused on physicians. Some patients say the restrictions have gone too far, but there are signs that the attention to prescriptions is slowing the rate of overdose deaths from prescription painkillers.

"Our prescribing has flattened out, but yet the opioid overdose has increased, mainly because of heroin," said Dr. Scott Weiner, who works in the emergency room at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and studies physician prescribing patterns.

Weiner says easy access to heroin on the streets is now fueling the epidemic.

Weiner is disturbed by what he learned from a patient he revived recently after an overdose.

"I said, 'How easy is it to get heroin?' And she said 'it’s ridiculously easy.' She said, 'I just call the dealer, he comes to my house and he delivers it within an hour,' " Weiner recalled.

Even delivered, heroin is pretty cheap, less than a pack of cigarettes in some states. Based on what he sees in the emergency room, Weiner predicts the epidemic won’t peak for several more years. That’s if public health and law enforcement can slow the supply of heroin and other opioids, which could be seen as the germs in this epidemic.

Dr. Sandro Galea, an epidemiologist and dean at Boston University’s School of Public Health, agrees that supply is the big open question.

"Have we seen the worst of this epidemic? Are we now going to be getting better and seeing fewer people dying from this? A lot of that is going to depend on availability through both legal and illegal means, and that’s very hard to tell," Galea said.

The illegal supply is thriving. A recent bust in Tewksbury took 30 kilograms of suspected fentanyl, another opioid considered 100 times more powerful than heroin, out of the disease pipeline.

Suffolk County Sheriff Steven Tompkins says so far, the dealers are winning.

"The abundance of this type of drug on the street is incredible, outrageous," Tompkins said, adding that dealers are giving away free samples. "When drug dealers can actually give it away it’s very scary. But they know that if folk get addicted to it that they’ve got a new client, a new customer, so they’re going to make that money back 100-fold."

Tompkins says the focus must be on education in homes and schools.

"We have to be very vigilant every day with telling people just how bad this stuff is, particularly with our kids," Tompkins said.

Public health workers and police are tracking the epidemic, looking at who is overdosing, when and where. Public bathrooms, for example.

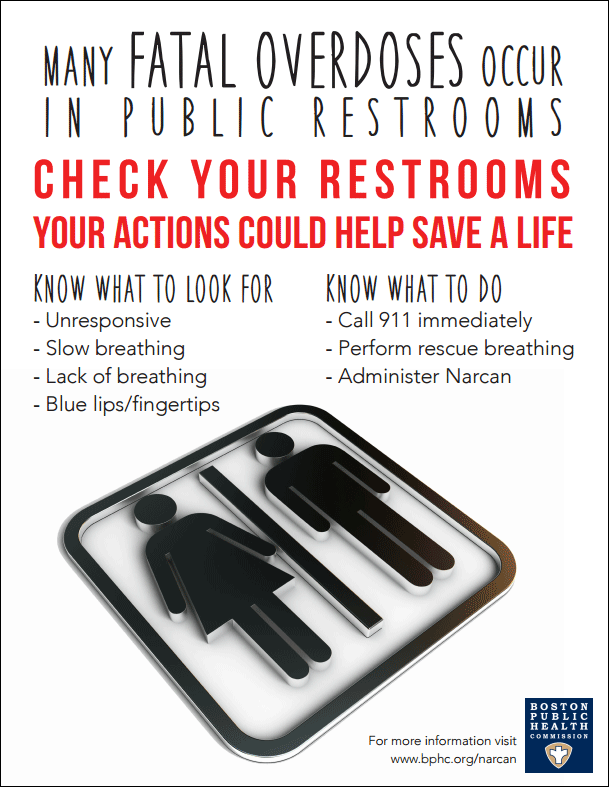

The Boston Public Health Commission is warning restaurants and public building managers to monitor restrooms and help avoid overdose deaths. Some police and EMTs are mapping so called hotspots, the locations of frequent overdose calls.

Epidemiologists say Massachusetts is doing a number of smart things to flight the epidemic, including the widespread distribution of naloxone, which reverses some but not all opioid overdoses, and passing Good Samaritan laws that offer immunity to friends or dealers who witness an overdose and call for help.

But "the fundamental question is whether what Massachusetts is doing is enough or whether it needs to do more," said Galea, who has studied substance use, addiction and interventions around the world.

And that will depend on many things: education, reducing the supply of opioids, easier access to treatment and continued monitoring to understand what’s happening with this epidemic.

With additional reporting by WBUR's Benjamin Swasey