Advertisement

How OxyContin's Maker Sought To Influence Mass. Legislators

Resume

Purdue Pharma, the maker of the popular and addictive painkiller OxyContin, believed legislators in Massachusetts could make or break its profits here.

Records in a January lawsuit, filed by Attorney General Maura Healey against Purdue and the family behind the prescription drug, show how they allegedly manipulated legislation at the State House.

Recently unredacted documents in the lawsuit and a WBUR analysis of campaign finance data show lawmakers faced a formidable foe behind the scenes.

From 2004 to 2018, Purdue paid lobbyists a total of $886,000 to protect its drugs, and the lobbyists also gave money to local campaigns hundreds of times.

Healey acknowledges companies lobby all the time, but she says Purdue’s grip on legislation in Massachusetts was based on greed that cost people’s lives.

She claims executives at Purdue, which is contemplating bankruptcy as it fights more than 1,600 lawsuits nationwide, bragged about killing bills and helping write a law in Massachusetts.

“The focus of my office … is to show the extent to which Purdue and individuals who we named in the complaint were attempting to influence or impact sales,” she said in an interview.

Attorneys for the family, the Sacklers, say in court documents that the family played no role in swaying legislation and that Massachusetts wasn’t the only state Purdue tracked. The lawyers report Purdue followed legislation in 31 states; in three states the company monitored policies that would limit opioids.

'2 Days Later She Died'

Former state Rep. Robert Fennell, a Lynn Democrat, witnessed the devastating effects OxyContin had on families.

He remembers at his Lynn restaurant, the Capitol Diner, having a great conversation with one of his regular customers and his daughter. She was in recovery from opioid abuse.

“She seemed like she was doing good,” Fennell said. “Two days later she died of an overdose.”

After that, in 2007, Fennell wanted to make OxyContin illegal, just like heroin. He introduced legislation several times, but got no traction.

“It was starting to become an epidemic and I was trying to be ahead of the curve,” he said.

He proposed an OxyContin ban again in 2013.

The attorney general alleges executives at Purdue realized Fennell's legislation would be catastrophic to their sales and developed a strategy to kill it.

Fennell had no idea Purdue allegedly claimed credit for quashing the bill.

Another former legislator tried to ban OxyContin, but his bill died too.

Steven Tolman, now president of the Massachusetts AFL-CIO, says when he was a Brighton-based state senator, Purdue lobbyists met with him several times, claiming the drug posed no harm.

"At that point these kids were on this drug and they were dying," Tolman said. “[Purdue's lobbyists would] stand there like they were saving people’s lives,” and then vilify those who became addicted.

Even one of Purdue’s board of directors, Richard Sackler, kept tabs on legislation.

Healey alleges Sackler alerted staff that Massachusetts wanted to limit how long someone could take addictive drugs like OxyContin. Staff allegedly promised a strategy to defeat it and lobbyists tracked the legislation.

Purdue hired local lobbyist Michelle McGee from 2004 to 2012. Charles Stefanini has been Purdue’s lobbyist since then. Neither would describe their work for the company, which also has an in-house lobbyist for the Northeast region.

Stefanini reported to the secretary of state that in 2013 alone, he tracked 112 bills for Purdue.

$410,000 Paid To Elected Officials And Groups

Since 2002, people associated with Purdue gave legislators, political groups and causes at least $410,000, based on a WBUR analysis of information from the Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance. The donations came from lobbyists, their spouses, the Sacklers and Purdue executives.

Massachusetts lobbyists can only give $200 per politician per year. Purdue representatives and their lobbyists gave money more than 1,500 times while working for the company, according to a WBUR tally.

In Massachusetts, money buys access to legislators, says Pam Wilmot, the executive director of Common Cause Massachusetts, a nonpartisan democracy group.

“It’s an unfortunate part of the political system where I think the public is the ultimately the loser,” Wilmot said.

Robert Josephson, executive director of communications for Purdue Pharma, says the company didn’t direct lobbyists to donate to policymakers.

“They are not just our lobbyists,” Josephson said. “They represent a number of other companies and I would have to say you’d have to ask them what their motivations are.”

Former Purdue lobbyist McGee says her contributions are personal. Current lobbyist Stefanini says he gives money to elected officials he works with.

“To suggest campaign donations are related to one specific entity is just patently false,” Stefanini said.

The lobbyists also gave money eight out of the last 10 years to the chairs of the joint committee that deals with substance abuse in Massachusetts.

Nationally, the Sacklers have contributed more than $1.6 million to federal candidates and elected officials, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

'Abuse-Deterrent' Legislation

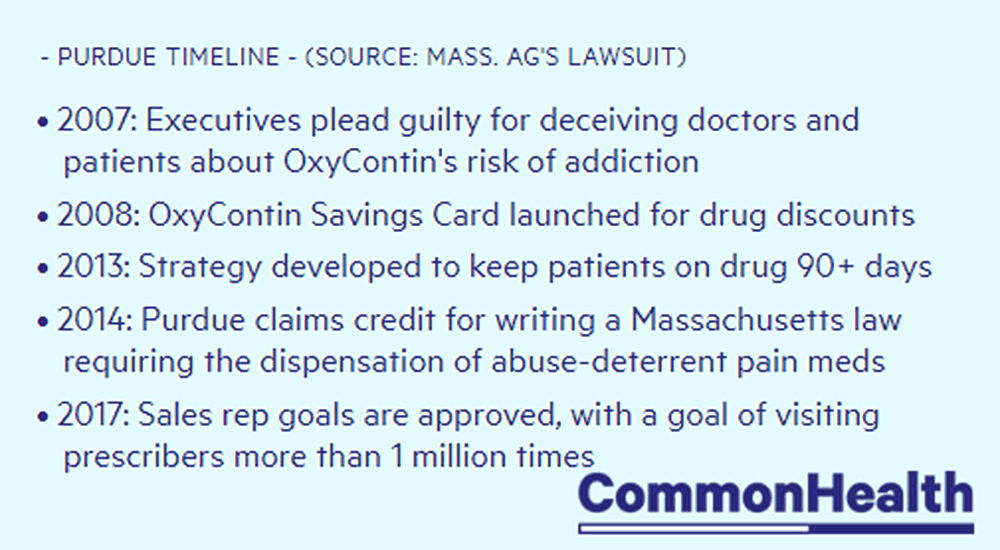

Purdue modified OxyContin in 2010 to make it impossible to snort or crush. Three years later the company promoted this new abuse-deterrent formula to legislators and claimed it would prevent overdoses, Healey's lawsuit states.

But the attorney general says the new product did nothing to prevent the most common cause of opioid abuse: swallowing the pills.

Sen. John Keenan, a Quincy Democrat, and several other legislators introduced similar bills in 2013 that would require pharmacists to fill opioid prescriptions with the abuse-deterrent formula, if one existed.

He says Purdue representatives never contacted him, but he knew their motivations.

“We were aware of them trying to get the patent that would allow them to be the only ones offering an abuse-deterrent formulation,” Keenan said. “They may have looked at it as beneficial because they maybe have the market cornered, but we were looking at saving lives.”

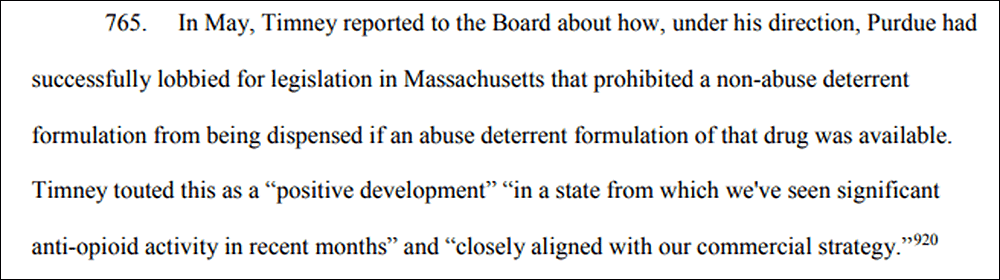

The attorney general says internal emails reveal staff at Purdue took credit for pushing their variation of the bill.

The bill passed unanimously and was signed into law in 2014. In court documents, a Purdue executive claims it was the first in the country.

Purdue's Josephson says the company had no financial motivation to push the law and that Purdue has made a positive impact in Massachusetts.

Wilmot, of Common Cause, says donations from lobbyists and company leaders can create suspicion.

“Was the decision because [lobbyists] made the best case, or was the decision made because they gave the most contributions? No one can answer that question,” she said.

This segment aired on April 25, 2019.