Advertisement

Dispatches From The Front Lines

COVID-19 Front-Line Diaries Show Pride And Pain For Health Care Workers In The Pandemic

ResumeMassachusetts is in the midst of a surge of COVID-19 patients.

Many people who work inside hospitals say this is the most challenging moment in their professional lives.

To help us grasp what’s happening, WBUR asked five front line hospital staffers, those in some of the highest risk positions, to record and share some of their experiences during what may be the peak in this wave of the pandemic.

April 12

David MacDonald, 38, is a nurse anesthetist from Belmont.

His duties include inserting the breathing tube that MacDonald hopes will support a patient’s lungs while they fight COVID-19. MacDonald estimates the mortality rate among patients he’s seen who go on a ventilator is about 70%. So the decision to intubate a patient is one of the biggest emotional challenges he faces.

"I hope this ends soon, but if it doesn’t, we’re here to take care of you.”

“I know when I put that breathing tube in that patient is probably not going to make it,” he says. “So coming in each day and looking at that list and seeing the patients that didn’t make it, that hurts.”

At the same time, MacDonald says he’s never been more proud to be in health care.

“The purpose for being at the hospital is greater than any other in our generation,” he says. “I hope this ends soon, but if it doesn’t we’re here to take care of you.”

April 16 and 19

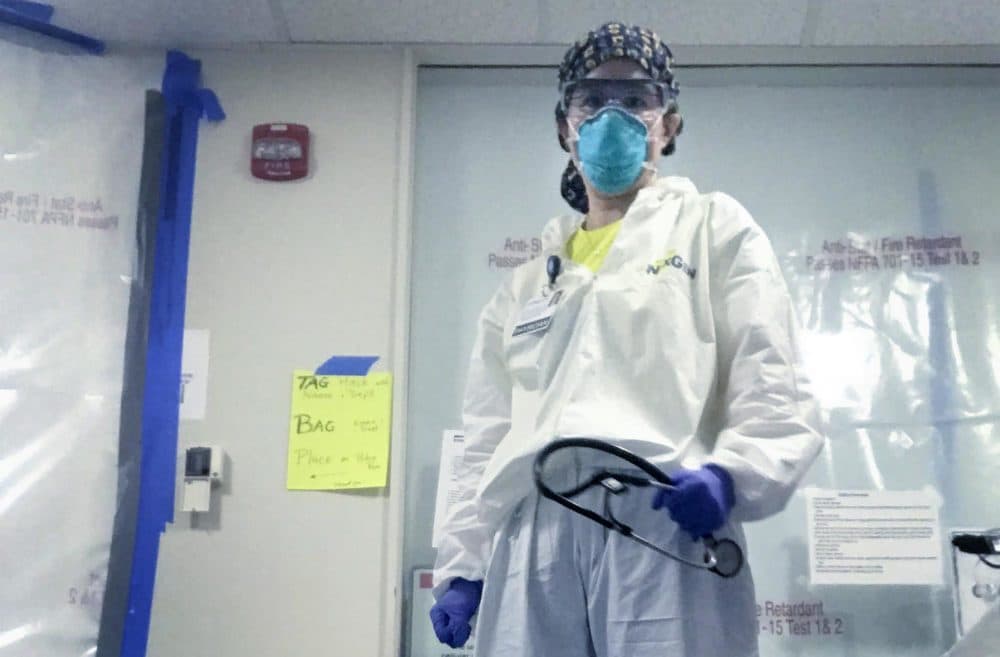

Dr. Melisa Lai-Becker, 47, is an emergency medicine physician from Somerville.

She suits up before each shift with safety glasses over her eye glasses, an N95 mask, a full body Tyvek suit and two sets of gloves that she can’t risk tearing.

“Despite the multiple layers of protection, I actually feel pretty naked,” she says, “because I leave my watch at home and my engagement ring and my wedding band.”

Lai-Becker is confronted often these days with what she calls very tricky situations. Some COVID-19 patients who are rushed to the ER need to be resuscitated and put on ventilators. Lai-Becker may learn later that a patient had a do-not-resuscitate order attached to their medical records via what’s known in Massachusetts as a MOLST form. Whether she’s authorized to intubate a patient or she is not, both experiences are “draining, exhausting and intense.”

April 20 and 21

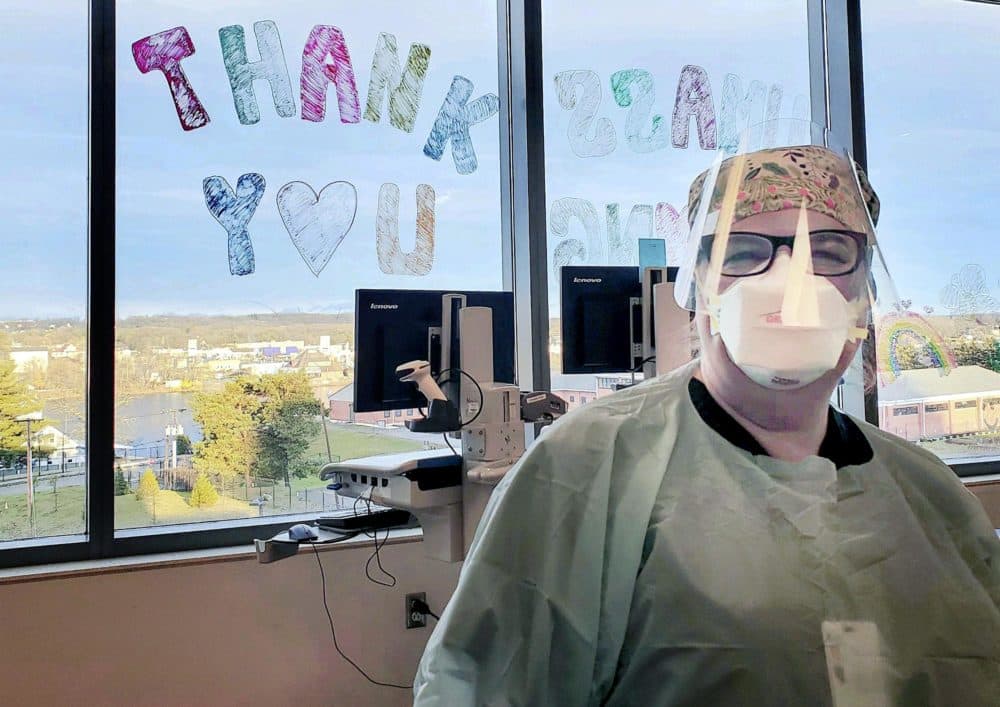

Barbara Braccio, 52, of Southborough, is a nurse in a COVID-19 ICU.

Braccio says the steady stream of patients are some of the sickest and most challenging she’s seen during 28 years of nursing. Braccio describes a lot of what she and her colleagues are doing as trial and error because so little is known about the disease. And every day is sad and impersonal.

“The patients are at such high levels of sedation, they are a person in a bed, but there’s no connection with them,” she says. “You don’t know them, you don’t know their family, you don’t know their story.”

When Braccio can speak to a family member on the phone, she’s struck by how difficult it must be to have a loved one in critical care and not know what’s going on — how they're forced to be “just taking the word of a total stranger that we’re doing the best we can to save them.”

Braccio is drained, physically and emotionally. She says there’s no such thing as an emergency in the ICU during the pandemic. Each shift is one long emergency.

“When I walk from the parking garage into the ICU, it’s probably the longest walk of my life because I just don’t know what I’m going into,” she says. “I just think to myself, ‘I hope this is the day after the surge and that my ICU will be cleared out,’ but that hasn’t happened.”

April 22

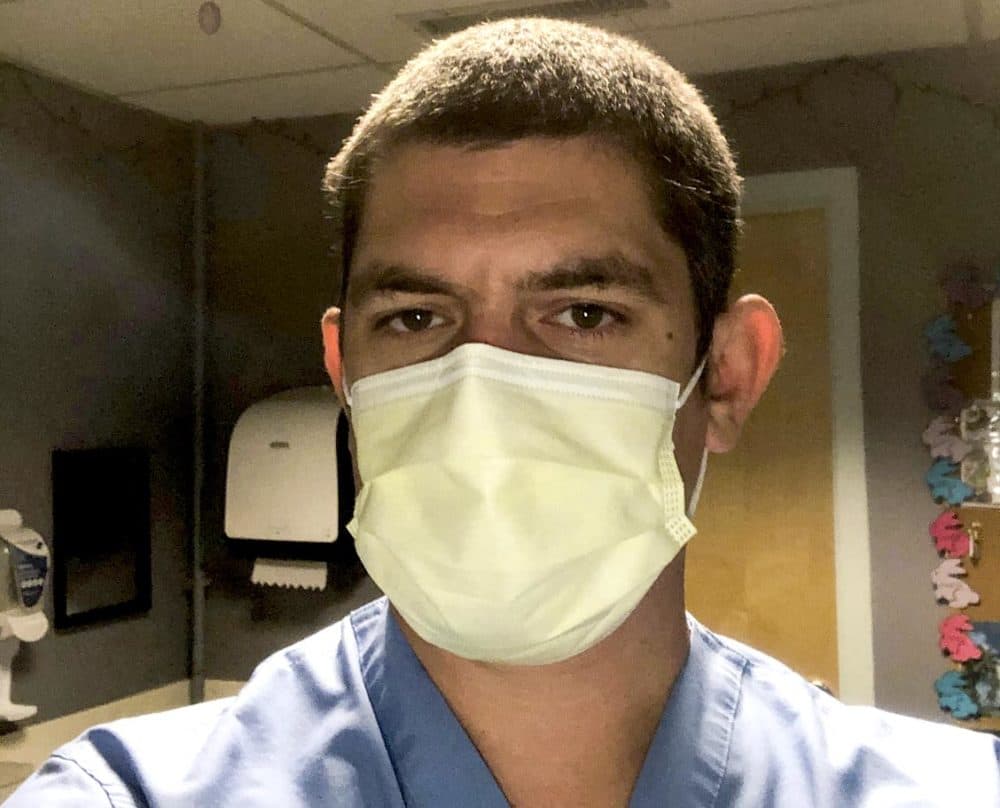

David Lesiczka, 39, is a radiologic technologist from Epping, N.H.

Lesiczka works at a hospital in northern Mass. where he takes chest X-rays of patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. Lesiczka says patients come in looking so nervous and scared and many go downhill fast.

It’s not uncommon to X-ray a patient coming into the hospital, and take another X-ray 45 minutes later to make sure their breathing tube is properly placed. Lesiczka says it takes two people to roll a patient who is sedated on a ventilator so that techs can take the image. But Lesiczka says the mental strain is worse.

“You look at a patient that you get very close to, to lift and put the plate behind, and you wonder, ‘is this the person that is going to give me this virus?,’” he says.

Lesiczka is inspired by co-workers who are “doing more than they ever dreamed they could to keep our community fighting and safe.”

April 23

Alba Lucia is a hospital housekeeper from Revere in her 50s.

She cleans and disinfects rooms that hold patients with confirmed cases of COVID-19, and those where she doesn’t know if the patient was positive or negative. Sometimes she must transition the room after a patient has died. Her emergency room is often full, but lately, she says it seems like there is no break in the flow of patients.

"We’re working really hard to keep up with the rooms,” Lucia says. “When you finish one, there are two or three more with people waiting. In many cases the patients are waiting outside.”

Correction: An earlier version of this post misquoted MacDonald. The rate he described is the mortality rate. The post has been updated. We regret the error.