Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Mass. Takes Close Look At Cluster Origins To Stop Coronavirus Spread

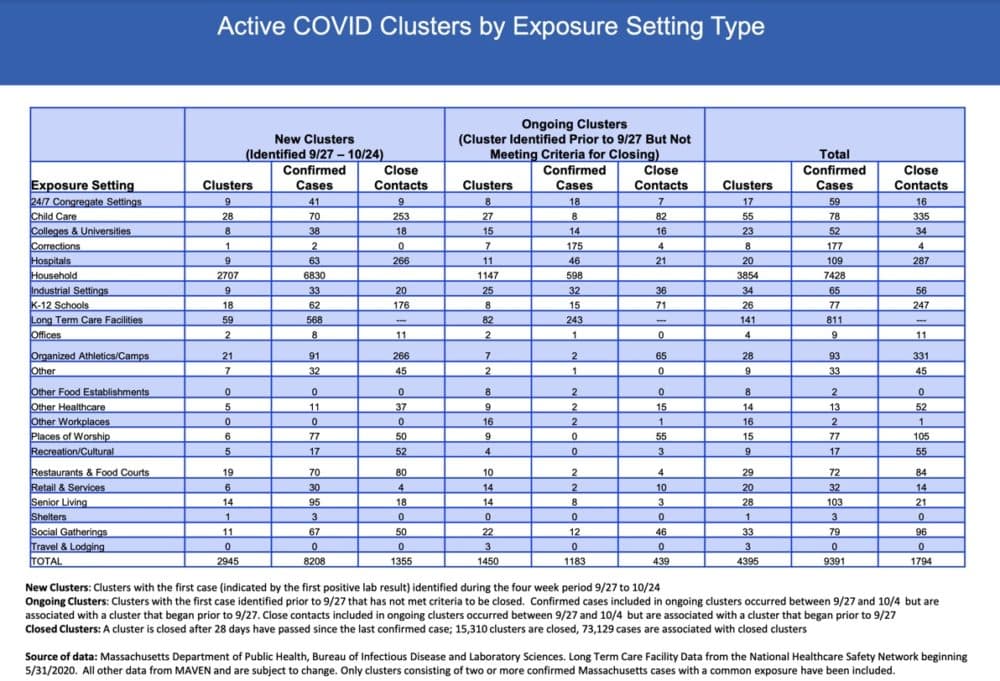

Clusters of the coronavirus are showing up in at least 22 different settings in Massachusetts, according to state data. The most common place with two or more active cases is in a home among residents. Other top spots for clusters or cases connected to them include child care centers, nursing homes, prisons and jails, industrial sites, hospitals and social events.

The state’s first public report that includes clusters looks at both new and ongoing cases during the past month. It shows that while most of 4,395 clusters are small, nearly half of the new cases reported since late September are connected to a shared setting.

Shelters, which were a source of widespread transmission early in the pandemic, now only show one cluster with three cases. There are just four clusters with a total of nine cases in offices. Colleges and universities, where some public health leaders feared an explosion of cases this fall, currently have 23 clusters representing 52 cases.

A spokesman for Gov. Charlie Baker’s administration said these findings shed more light on how and where the virus spreads — and how individuals can help stop it. Many people may let their guard down at home, for example. But the number of cases with a shared address suggests the need for masks and physical distancing if you live with an older person or someone who is more vulnerable to the virus.

Identifying clusters may help the state fashion targeted restrictions, instead of another broad shutdown, as cases, hospitalizations and deaths rise this fall and winter.

“Cluster reporting is one of the tools that will inform these decisions,” the spokesman for the Baker administration said. “Let’s look for the places that need adjustments or course corrections and we’ll look to affect change there.”

The administration points to hockey as an example. The state closed rinks for two weeks after recording at least 30 clusters and 108 cases. They are expected to reopen, but with additional safety and reporting requirements.

But the raw cluster and case numbers don't tell the whole story. Take households — there are a lot of them. So do the 3,854 household clusters in this report really highlight a greater risk of transmission than the 29 clusters in restaurants and food courts? To know, we need the denominator for each group, says William Hanage, an epidemiologist at Harvard's Chan School of Public Health. The state isn't publishing that analysis yet.

And, Hanage points out, it's easier to trace contacts under one roof as compared to in public spaces. But he says focusing on clusters is key because finding the people who are spreading the virus is more important than tracking every case.

That's the lesson from Japan, a lesson that persuaded the state's Contact Tracing Collaborative to shift more attention to clusters this summer. They talked to public health leaders in Japan who focus on the people and places with the highest rates of transmission.

“COVID is a clustering disease,” said Dr. KJ Seung, chief of strategy and policy for the Massachusetts COVID Response at Partners in Health, a member of the state’s Contact Tracing Collaborative.

“Most people will not spread to others but a minority will,” he said. “If you can figure out where that is happening, then you can intervene.”

But finding those clusters meant a shift in focus for some of the state’s contact tracing workforce. In addition to trying to prevent future infections by asking people to get tested and quarantine for two weeks, tracers needed to look two weeks back and figure out where someone who tested positive got infected. Early research shows that so-called “backward tracing” can be three times more effective than “forward tracing” at identifying people exposed to the coronavirus.

So the state created a unit of 15 experienced contact tracers who focus on the search for clusters. This Epidemic Intelligence Unit looks for cases where there may have been shared activities or events. They don’t try to trace back every case; they don’t have the resources or time.

Local health departments have done this kind of case investigation for years. Seung said collaborating with them now is especially important because they often know the pastor of a church or owner of a restaurant where a cluster may have occurred, and can get information quickly.

Seung expects more states will build backward or retrospective tracing and cluster analysis into their contact tracing programs. The Baker administration said Massachusetts is one of just a handful of states that is producing and publishing cluster information.

Hanage says backward tracking, cluster analysis, rapid testing to stop transmission, and widespread use of masks, together could reverse the rapid increase in cases across the U.S.

"None of these steps are game changers," he said, "but they are all parts of a more successful model."

Another key thing is cooperation. Baker has said too many people still don’t answer the call from a contact tracer or share information, about where they have been and who they have been in contact with, that could help prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

This article was originally published on October 30, 2020.