No Vacancy: How A Shortage Of Mental Health Beds Keeps Kids Trapped Inside ERs

One evening in late March, a mom north of Boston calls 911. Her daughter, she says, is threatening to kill herself. EMTs arrive, help calm the 13-year-old down and take her to an emergency room.

Like a growing number of children during the pandemic, Melinda has not been stable for several months. We’ll only use first names for this teenager and her mother, Pam, to avoid having this story trail the family for years to come. Right now in Massachusetts — and many parts of the U.S. and the world — demand for mental health care overwhelms supply, creating bottlenecks like the one Melinda is about to enter.

Emergency rooms are not typically places you check in for the night. If you break an arm, it gets set and you leave. If you have a heart attack, you won’t wait long for a hospital bed. But if your brain is not well, and you end up in an ER, there’s a good chance the crisis will become getting stuck there.

What’s known as emergency room boarding has been up between 200% and 400% in Massachusetts throughout the pandemic. The Baker administration says the rate of increase has varied each month since last June, but each month the numbers are significantly higher compared to the same month of the prior year.

“We’ve been doing this a long time, and this is really unlike anything we’ve ever seen before,” says Lisa Lambert, executive director of the Parent/Professional Advocacy League. “And it doesn’t show any signs of abating.”

Day 12

I meet Melinda, during a phone call, on her 12th day in the ER. The state says the average time children wait for hospital-based psychiatric care is six days, but many parents report spending weeks with their children in hospital hallways or overflow rooms, in various states of distress, because psychiatric units are full.

The state’s Health Policy Commission (HPC) says 39% of children who came to an ER with a mental health issue between March and September of 2020 ended up boarding.

Melinda’s first 10 days are spent in a hospital lecture hall with 11 or so other children, on gurneys, separated by curtains because the emergency room has run out of space. This is becoming more common across Massachusetts. A survey of emergency rooms earlier this year found a quarter of all beds, on average, occupied by mental health patients of all ages waiting for a psych bed.

At one point, Melinda tries to escape, is restrained, injected with drugs to calm her, and moved to a small, windowless room where everything brought in is screened and rejected if it can be used for self-harm. Melinda is disturbed by cameras in her room and security guards in the hallways who are there, in part, for her safety.

Advertisement

“It’s kinda like prison,” she says. “It feels like I’m desperate for help.”

Desperate is a word both Melinda and Pam use often to describe the prolonged wait for psychiatric care in a place that feels alien.

“We occasionally hear screaming, yelling, monitors beeping,” says Pam. “Even as the parent, it’s uncomfortable. It’s unsettling. It’s very scary.”

But this experience is not new. Pam says Melinda spiraled downward after a falling out with a close family member last summer. She has therapists, but some of them changed during the pandemic, the visits were virtual and she hasn’t made good connections between crises. This is Melinda’s fourth trip to a hospital emergency room since late November.

“Each time, it’s the same routine,” says Pam, starting with Melinda being rushed to an ER. Then, after a couple of days there, “She goes to a facility, she stays there for seven to 10 days and comes home.”

"We’ve heard waits as long as five weeks or more for outpatient therapy. If your child is saying they don’t want to live or don’t want to ever get out of bed again, you don’t want to wait five weeks."

Lisa Lambert, mental health advocate

Pam says each facility suggests a different diagnosis and adjusts Melinda’s medication.

“We’ve never really gotten a good, true diagnosis as to what’s going on with her,” Pam says. “She’s out of control; she feels out of control in her own skin.”

Melinda has been on a waiting list for a neuropsychiatric exam since last December. It could help clarify what she needs, although some psychiatrists say observing a patient’s behavior is often a better way to reach a diagnosis. She has an appointment for the exam, finally, for later this month. Lambert, the mental health advocate, says there are delays for every type of care.

“We’ve heard waits as long as five weeks or more for outpatient therapy,” she says. “If your child is saying they don’t want to live or don’t want to ever get out of bed again, you don’t want to wait five weeks.”

Day 13

As the wait drags on, Melinda bounces from manic highs to deep emotional lows. The emergency room is a holding area for patients who need psychiatric care. It isn’t set up to offer treatment or therapy. A mental health clinician stops in once a day to check on her. Pam says it’s a 10-15 minute visit.

Today, Melinda is agitated.

“I just really want to get out of here,” Melinda says, in one of several audio diaries she records and sends to WBUR. “I feel kind of helpless. I miss my pets and my bed and real food.”

Pam is disturbed to learn that Melinda had a panic attack the night before and had to be sedated.

“The longer she’s here, the more she’s going to decline,” Pam says. “She has self-harmed three times since she’s been here.”

Emergency rooms can ask the state to expedite a case after a child in need of a psych bed has been boarding for more than two and a half days or 60 hours. There’s a serious bed shortage now because more children need placements at the same time that COVID precautions have turned double rooms into singles or psych units into COVID units. The HPC says Massachusetts lost 270 psych beds during the pandemic due to COVID restrictions and units that closed.

Still, cases like Melinda’s are supposed to become a top priority.

The longer she’s here, the more she’s going to decline. She has self-harmed three times since she’s been here.

Pam, Melinda's mother

The hospital and its parent network, Beth Israel Lahey Health (BILH), declined requests to speak about Melinda’s care. But Dr. Nalan Ward, the network’s chief medical officer for behavioral health services, says all 11 BILH emergency department leaders gather for a daily call to discuss placement of difficult patients and other boarding issues.

On any given day, there may be 50-70 patients boarding throughout BILH. They may have medical or insurance issues that make them difficult to place. Many insurers say they have to approve a patient transfer before they’ll agree to pay for the placement, which can add delays.

“It takes a case-by-case approach,” says Ward. “It’s really hands-on, but we have very good success with some of the very difficult patients to place.”

For Melinda, the issue may be her behavior.

Day 14

Pam is told her daughter may be harder to place than other children who don’t act out. Hospitals say they look for patients who will be a good fit for their programs and other children there for treatment. Melinda’s chart includes the attempted escape as well as some fights with other patients and staff while she was housed in the lecture hall.

Today, Pam learns that two girls who arrived after Melinda, and might have been better behaved, have been transferred to psych units ahead of her daughter. As Pam sees it, this is another way Melinda is being punished because of her mental health.

“She’s having behaviors because she has a mental illness, which they’re supposed to help her with,” Pam says, “but yet they’re saying no to her because she’s having behaviors.”

And Pam says holding Melinda in isolation in the ER just makes things worse.

“She’s, at times, unrecognizable to me,” says Pam. “Mouthing off to staff members, causing drama with some of the other patients. She just is so sure that she’s never going to get better.”

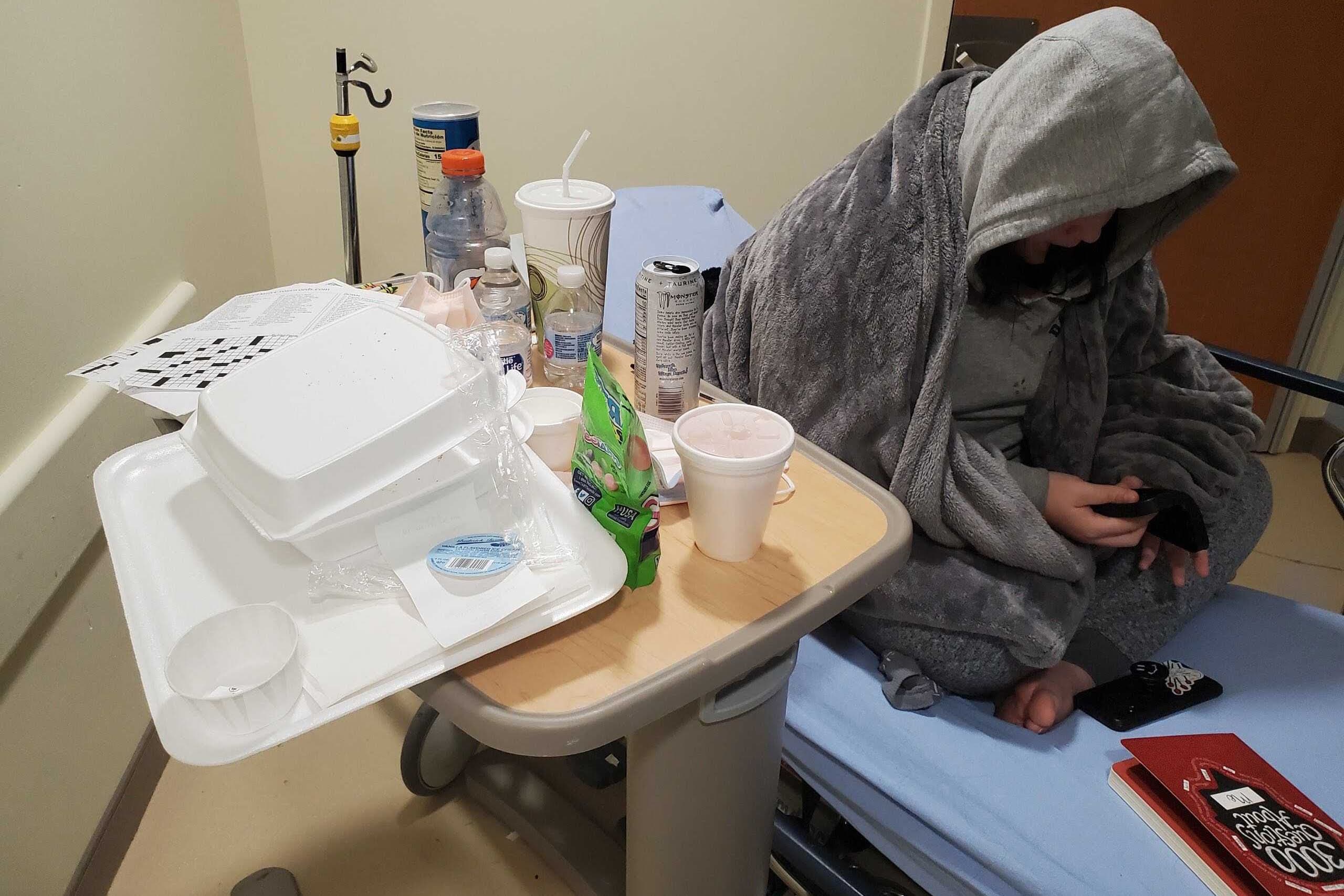

Melinda describes feeling increasingly isolated. She checks Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok during the hour each day when she can use her cell phone. But she’s lost touch with friends and most family members while in the ER. She stopped doing school work weeks ago. The activity of a 24/7 ER is getting to Melinda.

“I’m not sleeping well,” she says. “It’s tough here. I keep waking up in the middle of the night.”

Day 15

Boarding is difficult for parents, too. Pam, who is separated from Melinda’s father, works two jobs. But she visits every day, bringing Melinda a change of clothes, a new book, a fidget toy to help her stay calm or something special to eat.

“Some days I sit and cry before I get out of the car, just to get it out of my system, so I don’t cry in front of her,” Pam says. “Some days I’m just exhausted. Some days I’m excited to go see her. It’s different every day.”

Walking in, Pam says, “I kinda take deep breaths and mentally gather my strength.”

At the nurses’ station, she asks for an update. She’s told none of the hospitals that would seem to be good for Melinda have had an opening in two weeks.

Massachusetts has 357 licensed psychiatric beds for children. The state says 92 more are coming online. BILH says it will add four beds at Anna Jaques Hospital in Newburyport this fall, bringing that unit to 16. Cambridge Health Alliance says it will more than double its capacity from 27 to 69 beds for children by the end of the year.

Some hospitals say they can’t afford to care for patients with acute mental health problems because insurance reimbursements don’t cover costs. The Baker administration says it is spending $40 million this year on incentives. That includes $80,000-$150,000 for new beds that open in the next several months, and a more than 30% rate increase for children on MassHealth who need inpatient psychiatric care.

The Baker administration acknowledges that even with these changes, some patients still do not get timely care.

Emergency rooms are still flooded with boarding patients.

Day 16

“I never thought we’d be here this long,” says Pam.

When she checks in at the ER, the news is not encouraging. “I just don’t get the sense that anyone will have an opening anytime soon,” she says.

Emergency room doctors and mental health advocates are pressing the state for more public information about how many children and adults are boarding, where and for how long. A bill sponsored by state Rep. Marjorie Decker, a Democrat from Cambridge, would require more public reporting about children. The most recent information on the state’s boarding dashboard is from January.

The Baker administration emphasizes work is underway to keep children out of ERs and reduce the need for inpatient care by providing more preventive and community-based services. The state’s Roadmap to Behavior Health Reform aims to create easier access to mental health care, including new community behavioral health centers, urgent care for mental health patients and crisis centers outside of hospitals that would hold patients who are waiting for a hospital bed.

Dr. Jesse Rideout, a past president of the Massachusetts College of Emergency Physicians, says these are solid plans that may keep some people out of emergency rooms. But he worries that patients with severe mental illnesses won’t find these programs and will still end up in an ER.

“Those patients will need inpatient psychiatric beds,” Rideout says. “Our behavioral health boarding will not improve unless more beds are available.”

"Our behavioral health boarding will not improve unless more beds are available."

Dr. Jesse Rideout

Both parents and clinicians also question whether Massachusetts can find the counselors and psychiatrists to staff new community clinics, therapy programs and more psychiatric hospital beds. Dr. Ward, who oversees behavioral health care at BILH, says insurance payments are too low to attract and retain needed staff.

“We talk about increasing bed capacity and everything and then the next [thing] we talk about is ‘how are we going to staff it,’ ” says Ward. “There is definitely a workforce issue.”

By day 16, Melinda’s voice on the recordings is listless.

“Life is really hard because things that should be easy for everyone are just hard for me,” she says. “And when I ask for help, sometimes I picture going to the hospital. Other times, I wish someone would just understand me.”

Late that evening, there’s word Melinda’s protracted wait for care will end.

The Limbo Ends

Pam’s voice is shaking as she records the news.

“We finally got the call that she has a placement,” Pam says. “Hopefully, whatever help she gets this time sticks, and we’re not back at the ER in a few weeks, doing this all over again.”

On day 17, Melinda is taken by ambulance to CHA Cambridge Hospital. She’s lucky to get a spot. There are 50-60 cases of children who have been boarding more than three days in ERs who are on the waiting list for this one hospital during the week in April when Melinda arrives.

“That’s dramatically higher,” says Dr. Linsey Koruthu, medical director of the pediatric psychiatry in-patient service at Cambridge Health Alliance, “about double what we would have seen in 2019.”

"... when I ask for help, sometimes I picture going to the hospital. Other times, I wish someone would just understand me."

Melinda

At Cambridge Hospital, the staff adjusts Melinda's medications. Her days include meetings with a psychiatrist and social worker, group therapy, time for activities like schoolwork, yoga and pet therapy. Hospital staff meet with Melinda and her family. She stays two weeks, a bit longer than the average stay.

Doctors at Cambridge Hospital recommend that Melinda move from in-patient care to a community-based residential treatment program — a sort of bridge between being in the hospital and going home. But she doesn’t go. Those programs are full and have weeks-long delays.

Now Melinda is back home. She has three therapists helping her transition and use what she’s learned. And as COVID restrictions ease, some of those meetings are in-person with Melinda and her family.

Dr. Koruthu, one of Melinda’s physicians at Cambridge Hospital, says she thinks the in-person sessions will make a difference. Koruthu says therapists in virtual meetings can’t always see behaviors or family dynamics that might have contributed to some of Melinda’s crises or establish strong connections, particularly with new clients.

“A lot of mental health work is based on a therapeutic alliance,” says Koruthu, adding that virtual meetings haven’t worked for many children. “I think that has added to the influx of patients into our emergency room in the past year.”

Resources: If you're in mental health crisis, you can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) (Deaf and Hard of Hearing: dial 711 then 1-800-273-8255) and the Samaritans Statewide Hotline (call or text) at 1-877-870-HOPE (4673). Call2Talk can be accessed by calling Massachusetts 211 or 508-532-2255 (or text c2t to 741741).

This article was originally published on May 17, 2021.

This segment aired on May 17, 2021.