Advertisement

Closing Pilgrim

Timeline: The 52-Year History Of The Pilgrim Nuclear Plant

Resume

For more than five decades, the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station in Plymouth has been a controversial fixture in Massachusetts. Love it or hate it, by May 31, the plant will produce its last watt and shut down for good.

Here are some of the big moments in the plant's history.

1967

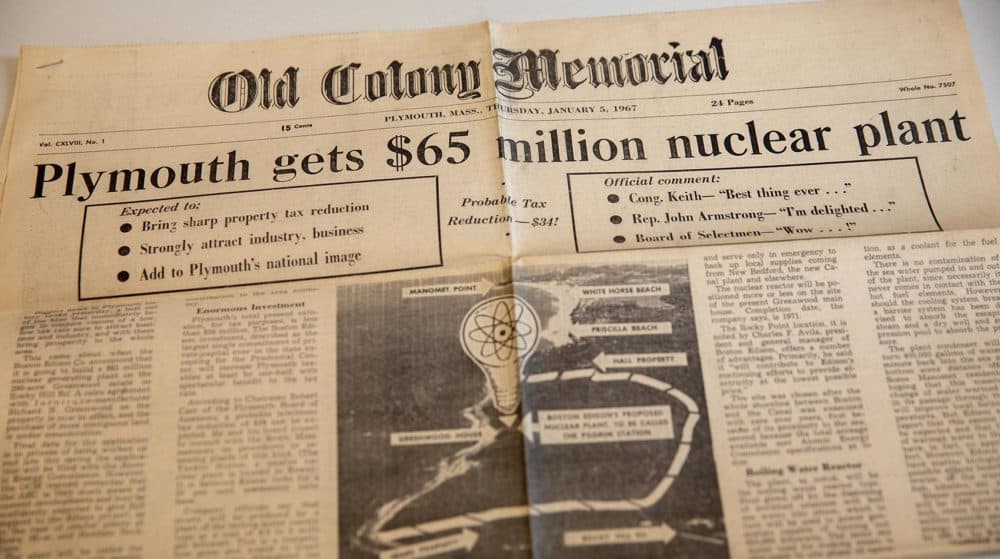

In 1967, Boston Edison Company announced it would build a nuclear power plant in Plymouth.

The decision made front page news in the local paper, which crowed that the plant would "add to Plymouth's national image." Also note the official comment from the Board of Selectmen: "Wow...!"

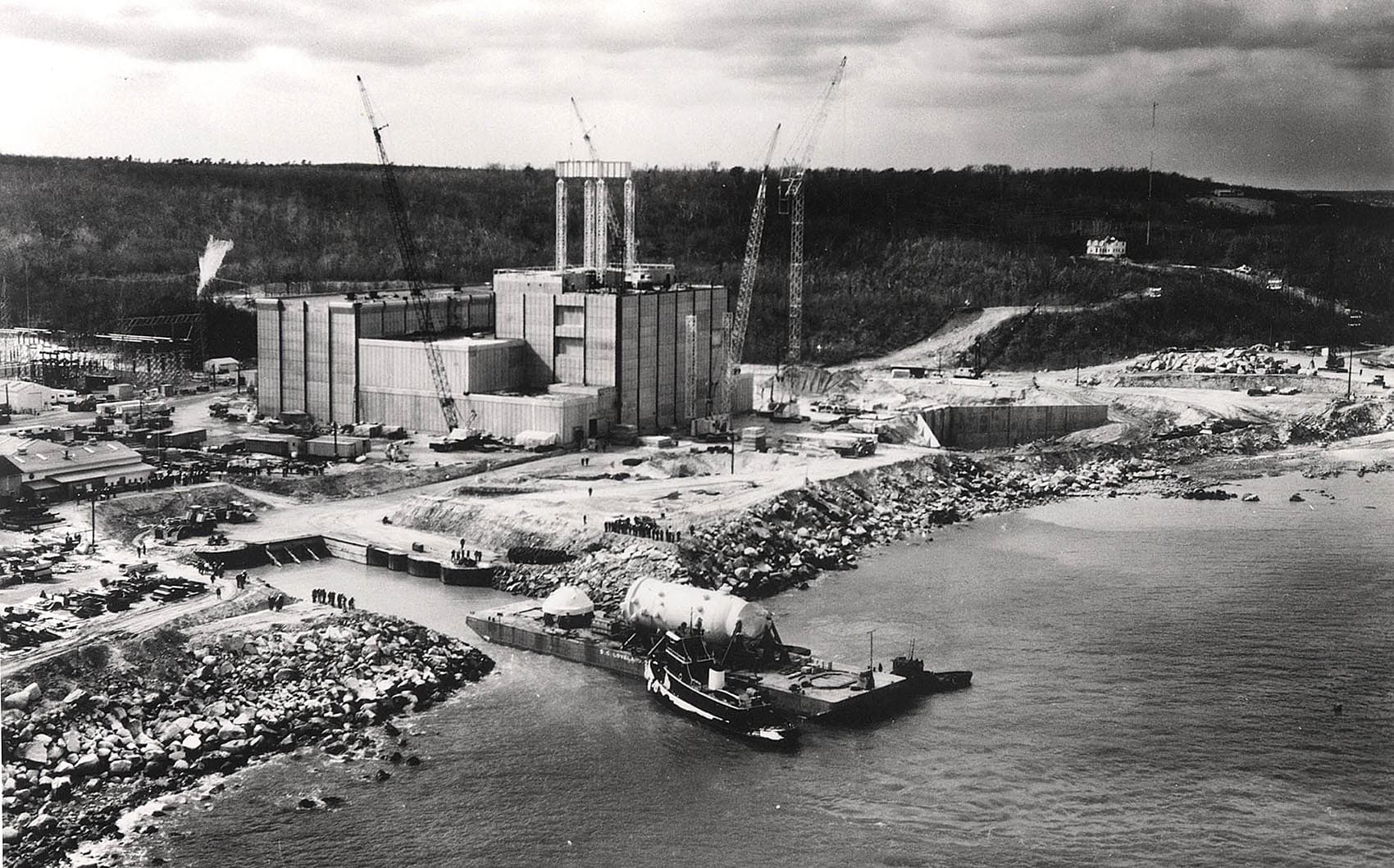

Construction began in 1968. It took about $231 million and more than three years to finish the Pilgrim plant.

The plant began generating power for the electrical grid in December 1972. Here are the original instruments and controls workers.

One Pilgrim employee, Paul Smith (bottom center, with glasses), says that "most of the young people starting at the plant in 1969-1970 had long hair, earrings, motorcycles and a Greenpeace card."

1973-1979

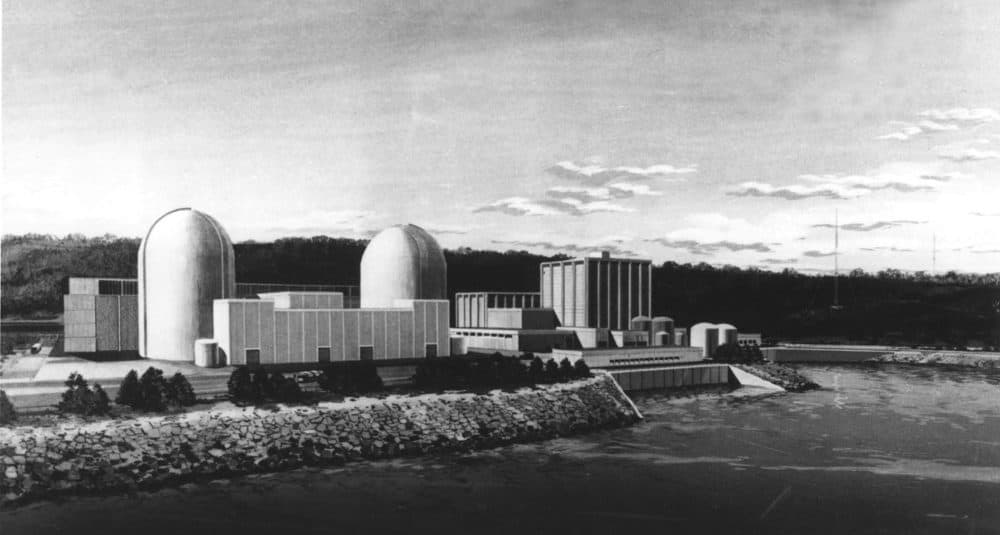

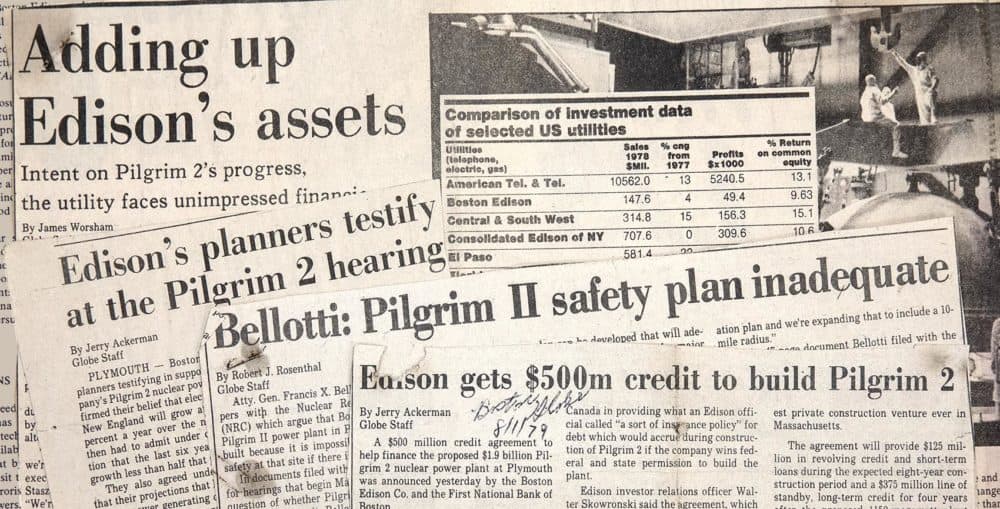

In the early '70s, Boston Edison proposed building two more reactors in Plymouth: Pilgrim II and Pilgrim III (the two domes pictured below). These newer models would be capable of generating much more electricity than the existing reactor, which is housed in the square building to the right.

There was immediate opposition to the plan — as well as growing opposition to the power station itself.

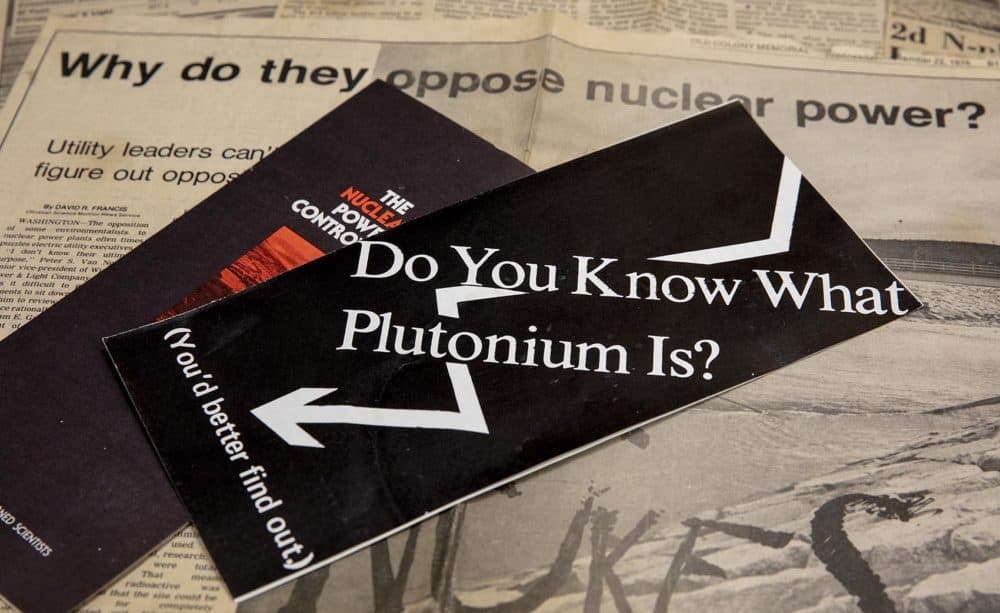

Plymouth lawyer Bill Abbott founded the anti-Pilgrim group Plymouth County Nuclear Information Center (PICNIC). PICNIC opened a storefront in downtown Plymouth to educate the public and distribute flyers. The group's first pamphlet (seen below) tackled plutonium.

"We ran kind of a public relations effort for a few months," Abbott says. "We got Ralph Nader to come to Plymouth, and we had a couple hundred people there."

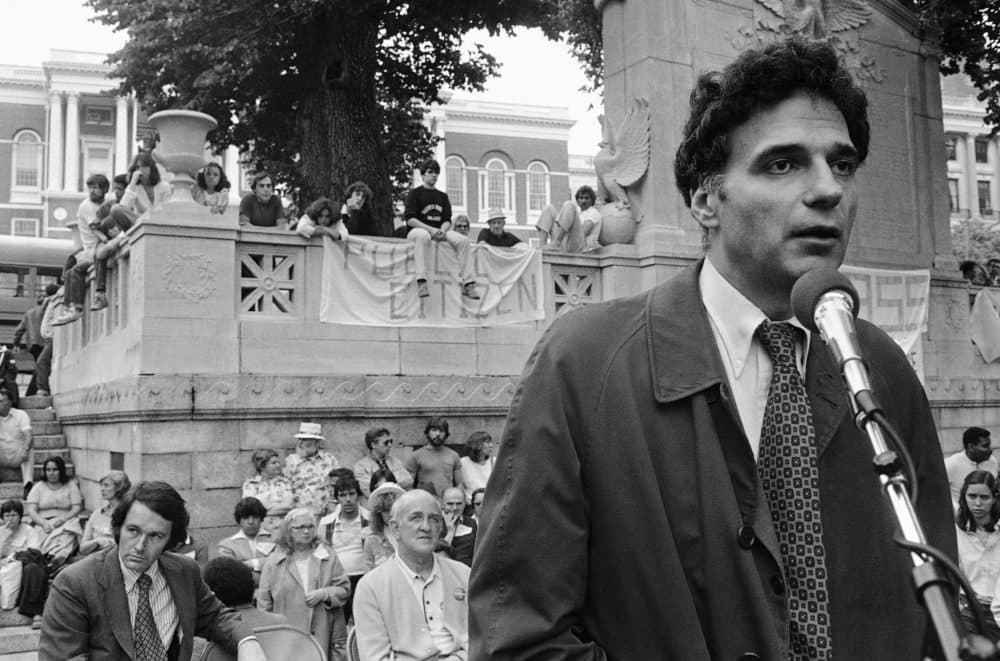

Nader is pictured below at an anti-nuclear rally near the State House in June 1979:

To slow down Pilgrim II and III, PICNIC went the legal route — challenging zoning permits and intervening in environmental proceedings.

Boston Edison scrapped plans for Pilgrim III in 1975, but continued to push for Pilgrim II.

While litigation dragged on, Edison spent millions building parts of the Pilgrim II reactor offsite. But in 1981, it cancelled the second reactor.

"Increased costs resulting from delays, additional regulatory requirements and the continuing uncertainty surrounding still other possible requirements forces this decision," Boston Edison CEO Thomas Galligan Jr. said at the time.

"On the day that Pilgrim II was [cancelled], there were already designs in place, there were already stakes in the ground," longtime Pilgrim employee Smith says. "The company gathered us together and the announcement was made in a very business-like, professional way. ... I didn’t have the depth at that time to step back and think that perhaps this is the end of the nuclear age."

1979-1989

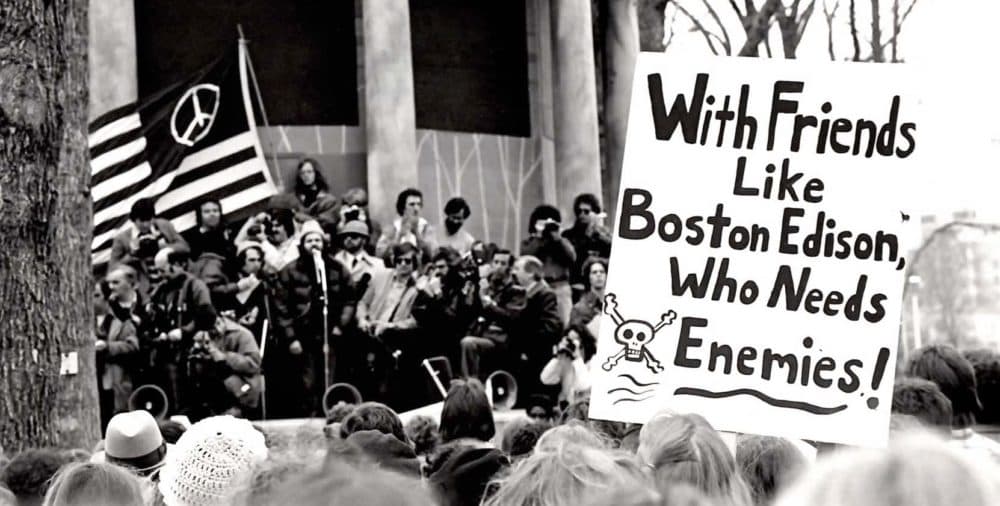

In the late '70s, Pilgrim began having mechanical and managerial problems. As the issues mounted, public opposition to the plant also grew. Anti-nuclear protesters frequently rallied in Plymouth and Boston. Here's a photo from a protest in 1979:

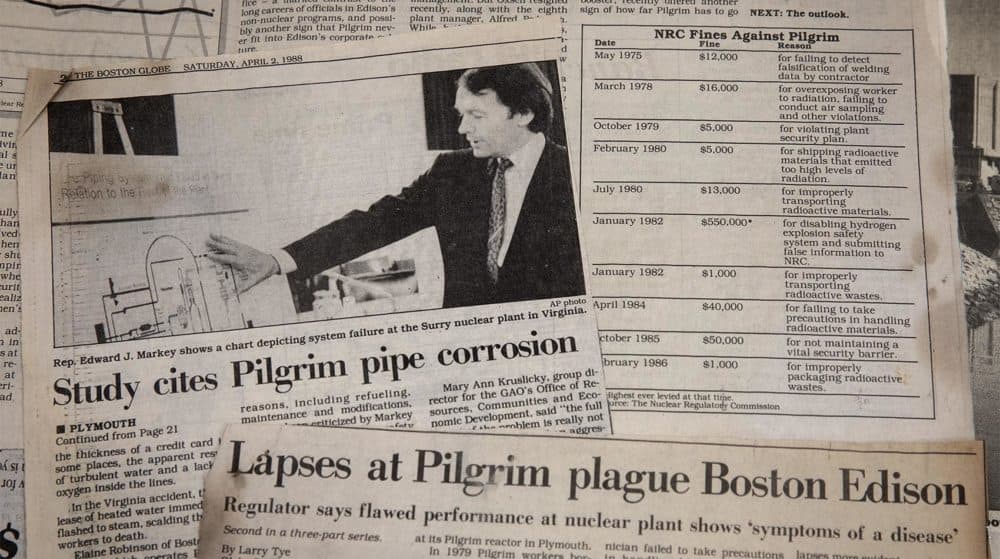

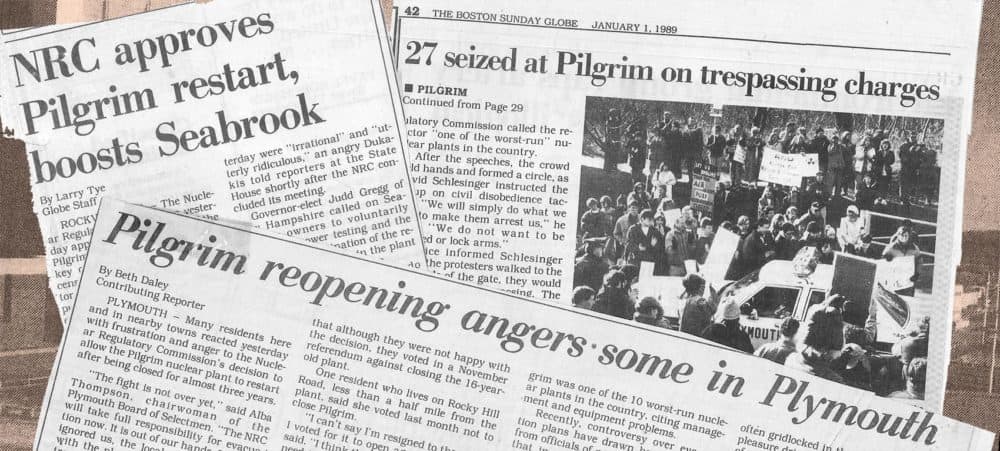

In 1982, the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission fined Boston Edison $550,000 for safety and reporting violations. In 1983 and again in 1986, the plant shut down for mechanical problems. The NRC dubbed Pilgrim “one of the worst-run" plants in the country.

After the 1986 shutdown, Boston Edison replaced many of the plant's top managers, and spent hundreds of millions fixing the plant.

In late 1988, despite opposition from Gov. Michael Dukakis, Attorney General James Shannon and U.S. Sens. Edward Kennedy and John Kerry, federal regulators said Pilgrim could reopen.

On Dec. 31, 1988, as the plant was powering up, 27 activists were arrested during a protest outside of the plant.

"It was very powerful because the folks - mostly women - were so strong, and they were really challenging the power. When they stepped over the [police] line, I followed because it seemed the right thing to do," says Diane Turco, one of the activists arrested that night. "Civil disobedience in our country has a very strong history of making change."

1989-1997

After the plant reopened, activists like Turco and Mary Lampert (below) turned their attention to emergency planning and public safety. They pushed the state Legislature to expand the Emergency Planning Zone from 10 miles to 50, and distribute potassium iodide pills to the public. The pills would protect a person's thyroid in case of accidental exposure to radiation.

Here's Lampert holding one:

Meanwhile, a state study raised concerns about a higher risk of leukemia near the plant, setting off a months-long debate in the Legislature.

1997-2011

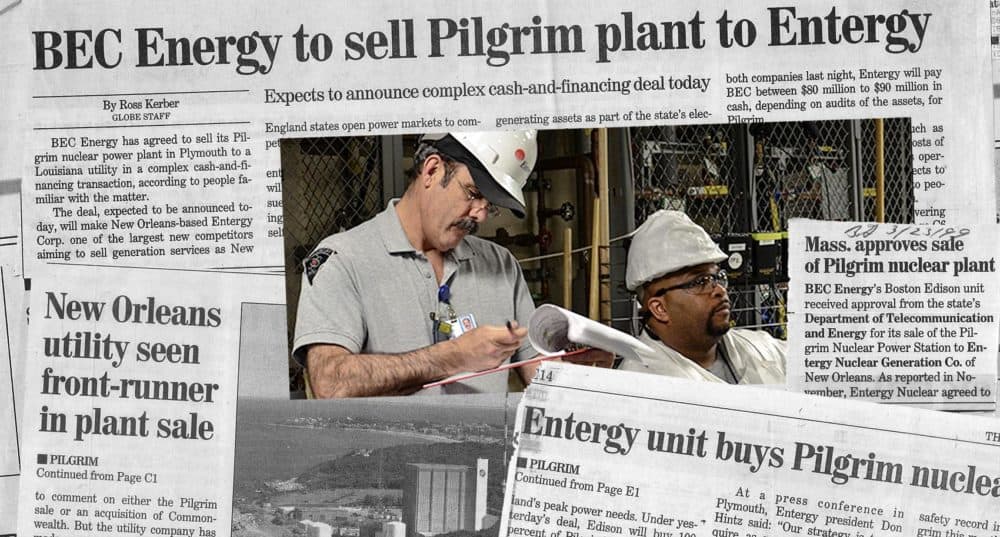

In 1997, Massachusetts deregulated the energy system. Boston Edison put Pilgrim up for sale and the Louisiana-based company Entergy Corp. purchased the plant for $80 million in 1999.

Two years later, the 9/11 terrorist attacks radically changed how the nuclear industry approached security. As seen below, the National Guard helped with Pilgrim's security in the aftermath of the attack.

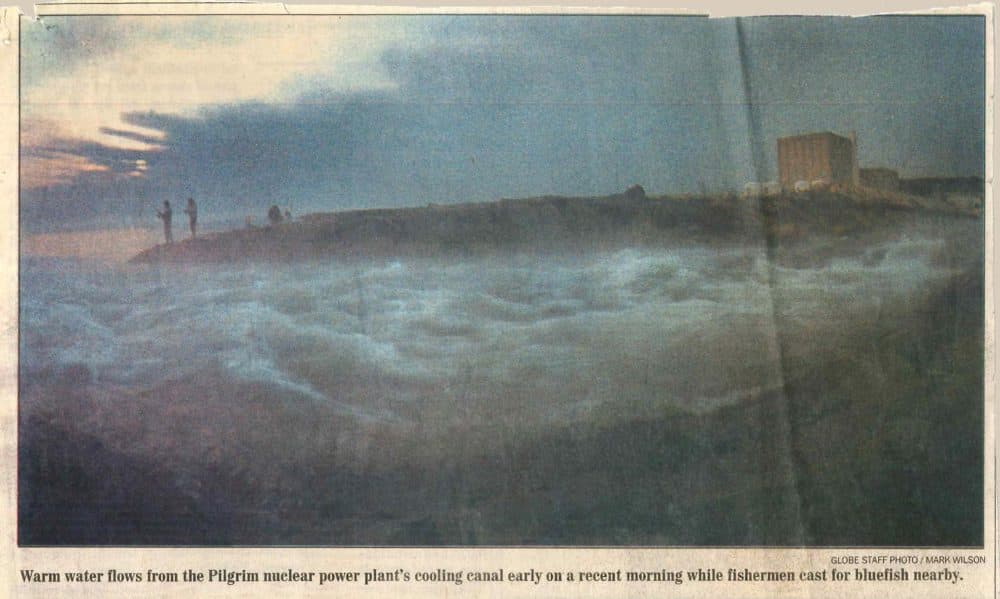

Prior to 9/11, the public had access to the area near Pilgrim. People fished in the warm waters near the water discharge canal (pictured below) or walked on the beach and hiking trails near the plant. This all changed after 2001.

On March 11, 2011, another tragic event touched Pilgrim. A magnitude 9 earthquake off the coast of Japan triggered a series of tsunamis that devastated much of the northeastern part of the country. The waves also drowned emergency backup generators at the Fukushima Daiichi plant, which, when combined with power outages, led to one of the worst nuclear accidents in history.

The Fukushima accident re-awoke the anti-Pilgrim movement, in large part because the two plants used the same type of reactor. If it could happen in Japan, it could happen here, anti-nuclear activists often said.

2012-2019

The growing anti-nuclear movement in Massachusetts coincided with a debate over whether the NRC should extend the plant's operating license. Entergy asked the NRC for a 20-year extension in 2006. For six years, local residents fought the re-licensing in court.

In 2012, with litigation still pending, the NRC voted 3-to-1 to extend the license. Those opposing the re-licensing were outraged.

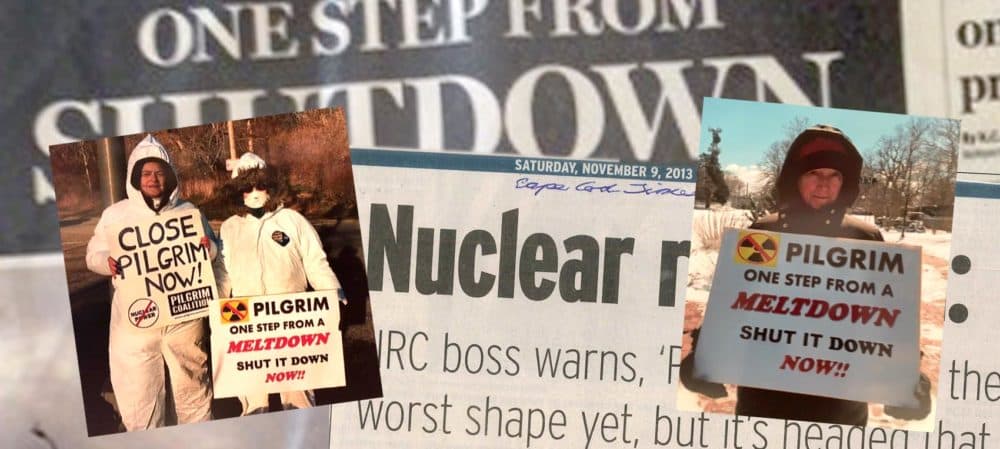

Around this time, mechanical and safety problems led to a series of shutdowns at the plant, which resulted in bad press and public outcry.

The NRC downgraded Pilgrim's safety status in 2014, deeming it one of the nine-worst reactors in the country. The following year, the NRC downgraded the plant again, making it one of the three worst-performing operating reactors and one step away from mandatory shutdown.

Meanwhile, the price of natural gas was decreasing, making the plant less profitable. In 2015, Entergy announced it would close Pilgrim by June 1, 2019.

Here's Entergy President Bill Mohl making the announcement:

Not everyone celebrated the news. Many in Plymouth were concerned about the closure because Pilgrim provides jobs for hundreds of people and a substantial amount of clean energy for the state.

In the summer of 2018, Entergy announced a plan to sell Pilgrim to Holtec International for decommissioning. Holtec already manufactures the dry casks used at Pilgrim (pictured below) to store spent nuclear fuel.

The two companies filed a joint-license transfer application with the NRC late last year, and are waiting for a final decision.

Meanwhile, the NRC upgraded Pilgrim's safety status in March, noting "sustained performance improvement" and "marked improvement in the site's safety culture."

Pilgrim will shut down in the highest safety rating category.

Newspaper articles and printed materials are courtesy of Christina Miller.

This segment aired on May 29, 2019.