Advertisement

Arsenic And Diesel As Thick As Peanut Butter: What’s Below The Future Weymouth Compressor?

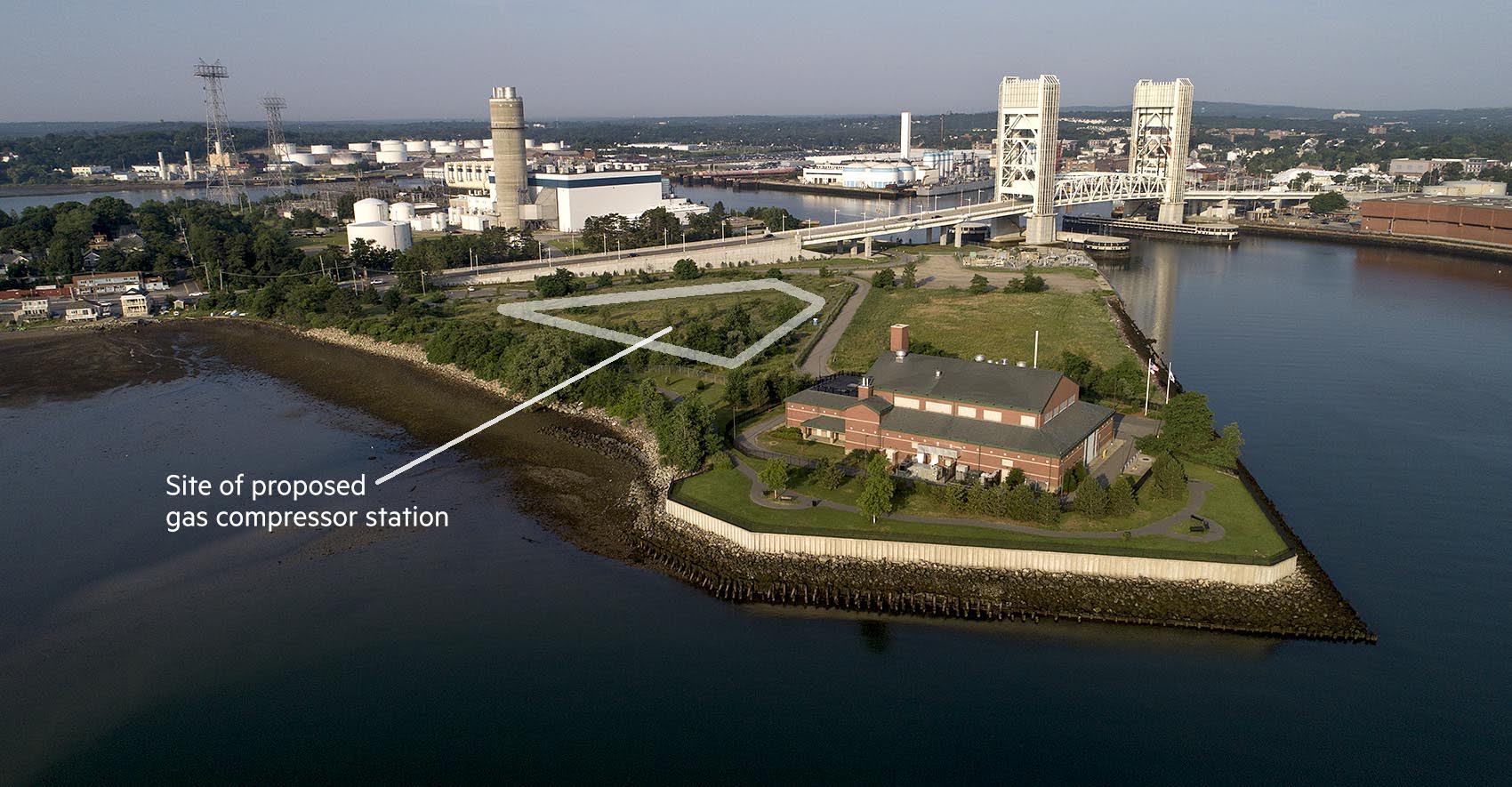

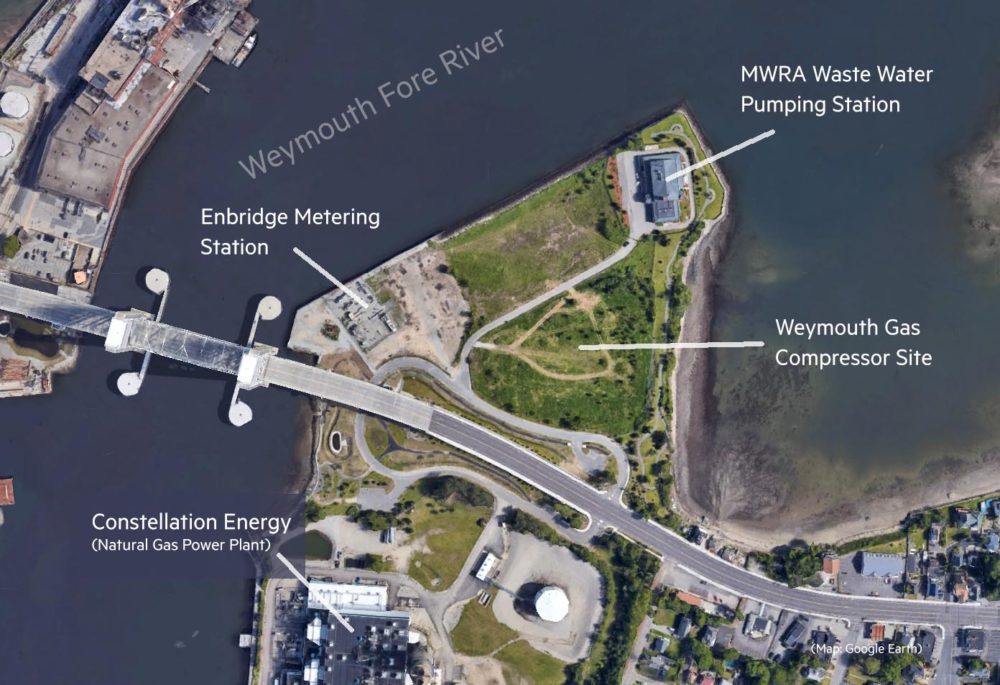

On the banks of the Fore River in Weymouth, just west of Kings Cove Park and north of Route 3A, there’s a triangular plot of fenced-in land. The future home of a natural gas compressor station, the space looks like any other grassy area. But just below the surface, a legacy of pollution from power plants fired by coal, oil and gas lingers.

Documents filed with the state show the dirt contains arsenic and coal ash, the lightweight, heavy-metal rich substance left after coal burns. And below ground, there’s a pool of old diesel fuel that one environmental expert working on the site said could have the consistency of peanut butter.

Exposure to heavy metals has been linked to cancer, impaired neurological development and other health problems, which is why Enbridge, the company behind the project, is promising to take precautions during construction and help clean up the property. But some in the Weymouth community — including the mayor, who has called the area a "hazardous waste site" — are skeptical of the company's plans.

So what’s in the dirt? And what’s the cleanup plan? Here’s what you need to know.

How Did The Site Get Polluted?

The peninsula jutting into the Fore River north of 3A — a piece of land comprising a wastewater pumping station, a natural gas metering station, Kings Cove Park and the future site of the compressor station — is known locally as the "north parcel." Much of the ground there, like in Boston's Back Bay, is made from landfill.

It's unclear when the fill process began and ended, but the shoreline that exists today was in place by the mid-1920s, when Boston Edison built the coal-fired Edgar Steam-Electric Station nearby. The company, which used the north parcel primarily to store coal, appears to have also dumped coal, coal ash and "clinkers" — hard, non-combustible material left after burning coal. There are also old furnace bricks scattered across the site, which many in the community worry contain asbestos (a claim Enbridge disputes).

In 1974, the company put an 11.2 million gallon above-ground storage tank on the north parcel. For decades, this tank leaked diesel fuel into the soil. Over time, the leaked fuel partially solidified and pooled underground (this is what one engineer said had the consistency of peanut butter). This substance is technically referred to as a light non-aqueous phase liquid (LNAPL), and to this day exists in viscous puddles under parts of the north parcel. In documents, Enbridge says tests show "limited or no LNAPL mobility," meaning it's not spreading or mixing into the groundwater.

The Edgar plant shut down in 1970. On the same site, the Fore River Energy Center, a natural gas plant, opened in 2003. Around that same time, the fuel tank was removed and the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority built a wastewater pumping station on the north end of the peninsula.

Enbridge purchased the property in 2016 and announced its plan to build the compressor station. Following state law, the company hired environmental experts to test the soil and groundwater. The results of those test confirmed what was widely known: the site is contaminated.

What Does State Law Say About This Contamination?

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) oversees hazardous waste site assessment and cleanup in the state, though its employees don’t do the actual work themselves. The job is privatized and contracted out to a licensed site professional.

Enbridge hired TRC Environmental Corporation to test the soil and design the cleanup plan for the Weymouth site. (For the sake of simplicity, this article will refer to Enbridge’s cleanup plans and reports, but just know that independent experts with TRC are the ones doing the work.)

So, after notifying the government of its plans to build a compressor station, Enbridge next had to figure out what exactly is in the soil and groundwater on the site, and whether the contamination poses a “significant risk” as defined by MassDEP.

The state uses a complicated formula to determine significant risk, but a lot depends on what the land will be used for — a plot of land that’s going to house an apartment building needs to be cleaner than one with a manufacturing plant on it, for example.

As part of this assessment, Enbridge looked at things like what contaminants are at the site, how much of each is there, how they got there, whether any of them are migrating into the water or air, and whether any of them could affect people, plants or animals.

If an assessment shows there's a risk, the company needs to design a cleanup plan. But if there’s no risk, they’ll submit what’s known as a Permanent Solution With Conditions Statement Report. In this context, "with conditions" means that if, in the future, the owner wants to use the land for something else, they'll have to do a new assessment.

It’s all very complicated, but what you need to know is that the permanent solution statement signifies the end of the cleanup process; it’s like a big report — written by a hired outside expert — that proves that the land in question is clean enough to be used for a specific purpose.

In the case of the Weymouth Compressor, Enbridge submitted its permanent solution statement to MassDEP in December 2018. The four-volume assessment shows that there is arsenic and a few hydrocarbon compounds in levels that exceed state limits, but concludes that these things don’t post a “significant risk” to public health.

Put another way, the report says that because no one lives on the property, and there’s little evidence that the hydrocarbons in the soil are leaching into the groundwater, the safest place to keep the contamination is right where it is: buried underground.

MassDEP audited the report in April, and concluded that it didn’t meet state hazardous cleanup standards. The agency questioned how the company classified the landfill on the north parcel and whether the size of the peanut-buttery diesel fuel puddle was properly calculated. Enbridge was instructed to do more testing and resubmit the permanent solution report.

Why Does The Kind Of Landfill Matter?

Remember how we said the compressor is going to be built on property made from landfill? Well, not all landfill is created equal. Up until the late 19th century, people created landfill out of all sorts of things — garbage, industrial waste, even dead farm animals. Once they realized how dangerous it was to spread trash and other toxic materials all over the place, they switched to safer materials. To this day, state law reflects that shift, and landfill built after the 20th century is held to higher cleanup standards than historic fill.

Enbridge said in its plan that the north parcel was made from historic landfill, and therefore only needed to meet the more relaxed contamination levels — standards that don't include assessing the risk of heavy metals in the soil. MassDEP disagreed, and said the company's new report must look at whether contaminants like arsenic are leeching into the groundwater.

The company will also have to calculate exactly how big the diesel fuel puddle is, and what risk it might pose.

The company has until Jan. 17, 2020, to submit an updated permanent solution report or to withdraw the report and propose a cleanup plan.

But Wait, Didn't Construction Already Start?

Great question. Yes, Enbridge announced just before Thanksgiving that it planned to break ground in early December. According to company filings, the compressor will take about 10 months to build.

So how can they start building without the cleanup plan in place? Well, another provision of Massachusetts’ hazardous waste laws concerns something called a Release Abatement Measure — RAM plan, for short.

(We told you, this gets complicated.)

RAM plans are voluntary and allow property owners “to take early and prudent response actions to address clear and obvious contamination,” a state explainer video says. They also help “to speed the process along” because they can be implemented before, during, or after construction.

Think about it like this: Let’s say you want to build a factory on a piece of land you know has a history of contamination. You’d hire an outside expert like TRC to study the soil and groundwater, and determine whether the pollution poses a “significant risk.”

If the answer is yes, TRC helps you devise a cleanup plan; if the answer is no, you’ve effectively ended the mandated cleanup process and can submit a permanent solution plan; and if the state conducts an audit, you might have to go back to do some more testing.

Whatever the outcome, the permanent solution plan is about what exists on the property now, and filing it is a signal you’ve finished the cleanup.

Recall that the whole reason you have this property is to build a factory. This is where the RAM plan comes in. RAM plans are like the blueprint for small cleanup projects you choose to do; the incentive for a company to implement one is that they can be done before or during construction, so the whole project moves faster.

For your hypothetical factory, you might need to excavate a big part of the property to put in the foundation, and the RAM plan lays out what remediation measures you’ll do at the same time.

In the case of the Weymouth Compressor, Enbridge’s RAM plan focuses on “the excavation, handling and use or disposal of approximately 15,000 cubic yards of the existing fill at the property.” It also spells out “plans [to raise] the grade of portions of the property by at least 3 (and in some areas over 5) feet.” Both of these measures will almost certainly improve the contamination problem at the site, but again, have no bearing on what Enbridge writes in the permanent solution report it needs to submit in January.

Enbridge submitted its RAM plan on Nov. 25, and two days later, Weymouth Mayor Bob Hedlund asked MassDEP to review it. He also asked that any work on the property be suspended until the review is complete.

In a statement, a spokesman for Enbridge said the company "is committed to ensuring the site meets applicable environmental regulations, and to ensuring any work at the site is conducted safely and in compliance with all applicable environmental requirements, with public health and safety as our priority."

What Happens Next?

As of the first week of December, construction on the site has started. And unless MassDEP intervenes in the process — something two outside environmental experts said was unlikely -- the work will continue.

Opponents of the project say they're worried about construction workers being exposed to arsenic-laden soil, and about the truckloads of soil that will be carried away from the site. Enbridge says it will follow all state and federal safety laws when it excavates the site and transports material to waste disposal sites in Westminster and Taunton, Mass., as well as Rochester, N.H. and Norridgewock, Maine.

In the meantime, MassDEP and Weymouth are waiting for Enbridge to submit a revised permanent solution plan in January.