Advertisement

First, A Pandemic. Now, The Heat. Why This Summer Poses Extra Risks For Older Adults

Public health officials often refer to heat as a “silent killer.” While an estimated 12,000 Americans die from heat-related health problems every year, high temperatures tend to get less attention than other weather extremes.

Heat is also not an equal opportunity killer. For a variety of reasons, older adults are far more susceptible to heat-related illnesses; studies, in fact, show that they account for the vast majority of excess deaths during heat waves.

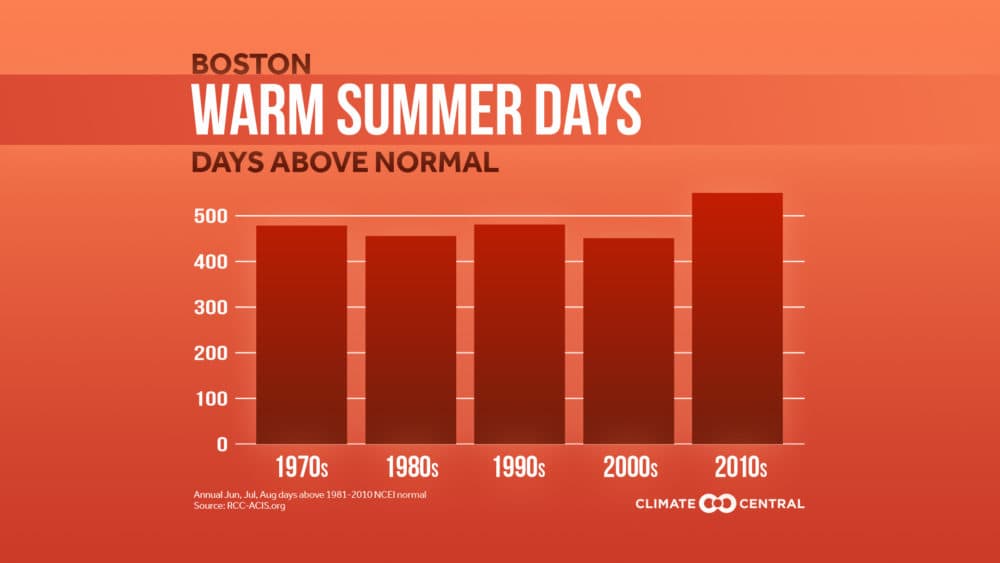

And this summer, public health experts in the Northeast are particularly worried. Not only is this predicted to be one of the hottest summers on record, but the coronavirus pandemic is both exacerbating the risks older adults face, and complicating the traditional solutions people have used to keep them safe.

Consider Bruce Matthews, a 69-year-old Chelsea resident. Up until a few months ago, Matthews, who has vision and diabetes-related mobility issues, lived at the local YMCA.

“In a way I kinda liked it because it had a swimming pool, a steam room, gym, basketball court,” he says. “You just couldn’t get it any better.”

Well, except for the heat.

“The heat! Oh my god, the heat in there — you didn’t even have to go into the kitchen to cook food. You could cook food in your room,” he says. Like all residents of the building, Matthews slept in a small room with one window. He wasn’t able to install an air conditioning unit, and the fan he kept going 24/7 during the summer just didn’t cut it.

“Sometimes I’d wake up and I thought I was in the swimming pool downstairs, there’d be so much water coming out of my back,” he says with a laugh.

“The heat! Oh my god, the heat in there -- you didn’t even have to go into the kitchen to cook food. You could cook food in your room.”

Bruce Matthews

So he had to find other ways to cool off. Catching the bus to nearby Revere Beach was a favorite option. He would pack a sandwich and some juice and “go down to the beach and just let that sea breeze hit.”

After nine years of living in the YMCA, Matthews finally got placed in a senior housing complex just down the street. His new apartment is sunny and spacious, and best of all, has air conditioning and a powerful fan.

On a recent FaceTime call, Matthews says he feels so lucky to have moved in prior to the pandemic because taking public transportation to go to sit on a crowded beach doesn’t feel like a safe option this summer.

But other older adults aren’t so lucky.

“I’m deeply concerned about this summer. I mean, first of all, all signs are that this is going to be one of the hottest summers in recorded history, so there would be a lot of risks of heat deaths, heat illnesses, regardless of COVID-19,” says Eric Klinenberg, a sociologist at New York University who studies climate-related public health issues in urban areas.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, older adults have a harder time than younger people adjusting to temperature changes. They are also more likely to have chronic health issues or take medications that affect their body’s ability to stay hydrated.

Klinenberg says that even in the best of times, older adults are more vulnerable to extreme heat events. And these definitely are not the best of times.

“With the pandemic, we have asked people to stay at home and to maintain physical distance to survive — we have given that message especially to older people. But unfortunately, that also places them at greater risk of heat stroke, heat illness and heat death,” he says.

Advertisement

In fact, it’s kind of a perfect storm.

“If you drew a map of who is vulnerable to COVID and who is vulnerable to heat, it would look very similar. It’s not exactly the same, but older people, people with underlying health conditions, poor African American neighborhoods, have been extremely vulnerable to COVID and they are also the most vulnerable to heat waves,” he says.

Dr. Hollis Day, chief of Geriatric Medicine at Boston Medical Center, is also worried about how heat will affect her patients over the next few months. Many older adults live on fixed incomes and either can’t afford air conditioning or are reluctant to turn it on, she says. And for them, the places they’d normally go to cool down — community cooling centers, senior centers, even restaurants and air conditioned stores — are either closed or are places they’ve been told to avoid because of crowds.

“These are very vulnerable people in so many ways,” she says. “They’re vulnerable to the virus, they’re vulnerable to heat.” And they’re vulnerable to social isolation.

Between mobility issues and fears about taking public transportation, Day says this summer poses new and unique challenges for many older adults.

“Where we have had people in the past have an older adult buddy that you would check in on — with COVID, I don’t know what will happen to that [practice]. Inviting someone into your home is a little more challenging right now,” she says.

To the extent you can, Day suggests regularly calling the seniors you know to check in — especially those who live alone — and dropping off bottled water to make sure they stay hydrated.

"... oftentimes when your body begins to breakdown from heat-related illnesses, you can’t tell just how much trouble you’re in. So what makes the difference between life and death … is whether you have another person there with you to give you a hand."

Eric Klinenberg

Klinenberg, the NYU sociologist, agrees. In his research for a book about the July 1995 Chicago heat wave that killed over 700 people, he discovered that social isolation was one of the leading epidemiological risk factors for death.

Older adults “are more likely to live alone and to lack social support and face-to-face contacts,” he says. “And that’s important during a heat wave because oftentimes when your body begins to breakdown from heat-related illnesses, you can’t tell just how much trouble you’re in. So what makes the difference between life and death … is whether you have another person there with you to give you a hand.”

From local government officials to family members or neighbors of older adults, we all need to “understand the connection between heat risk and COVID risk, and how those two might compound each other,” he says. “Because the truth is, with climate change, the dangers of heat are only going to get greater.”

Back in his Chelsea apartment, Bruce Matthews says he’s doing what he can to keep cool.

“Because there’s a pandemic, I’m not going to the beach this year. The shower — that’s about as far as I’ll get into the water," he says. "I’m not messing with this pandemic, not at all.”

This segment aired on July 17, 2020.