Advertisement

Study Finds Significant Racial Disparities In Vehicular Air Pollution Exposure Around Boston

A new analysis from the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) finds that people of color in the Greater Boston area are more likely to live near a major roadway that exposes them to high levels of vehicular air pollution.

The findings are especially relevant now, since air pollution can cause or exacerbate the underlying health issues that increase the likelihood of dying from COVID-19.

“Medical conditions like pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease and diabetes are associated with exposure to a variety of air pollutants [including] ultrafine particulate matter, which is the smallest size of fine particulates emitted predominantly by diesel powered vehicles like heavy trucks,” says Conor Gately, co-author of the report and a senior land use and transportation analyst at the MAPC, the regional planning agency for the metropolitan Boston area.

Gately and his colleagues set out to pinpoint which roadways had the highest levels of ultrafine particulate emissions and who lives near them. The results, he says, are a stark reminder of the deep connections between human health, the environment and structural racism.

“As we suspected, there are inequities in the spatial patterns of where different races of people live across the region," Gately says. "And by and large, there is a significantly higher portion of residents of color living very close to these high polluting roads compared to their share of the regional population.”

Many people in the MAPC region, which covers 101 cities and towns within the I-495 corridor, live 150 meters or less from a big road — 88% of residents, to be precise. But not all roads are created equal. Large trucks frequent some streets, while idling cars and traffic jams clog others. So to determine the highest polluting roadways, researchers first had to determine something called the Pollution Proximity Index, or PPI.

PPI is a relative measure, on a scale of 1-5, of things like traffic patterns, proximity to other roadways and closeness of houses to the road. A lower PPI value is better. Areas with high PPI values tend to be near more than one busy road or highway or have a lot of truck traffic, while areas with lower PPI values are near smaller, quieter roadways and may have homes that are set further back from the road. (Ultrafine particulate matter dissipates quickly, so how close a given home is to the roadway matters a lot.)

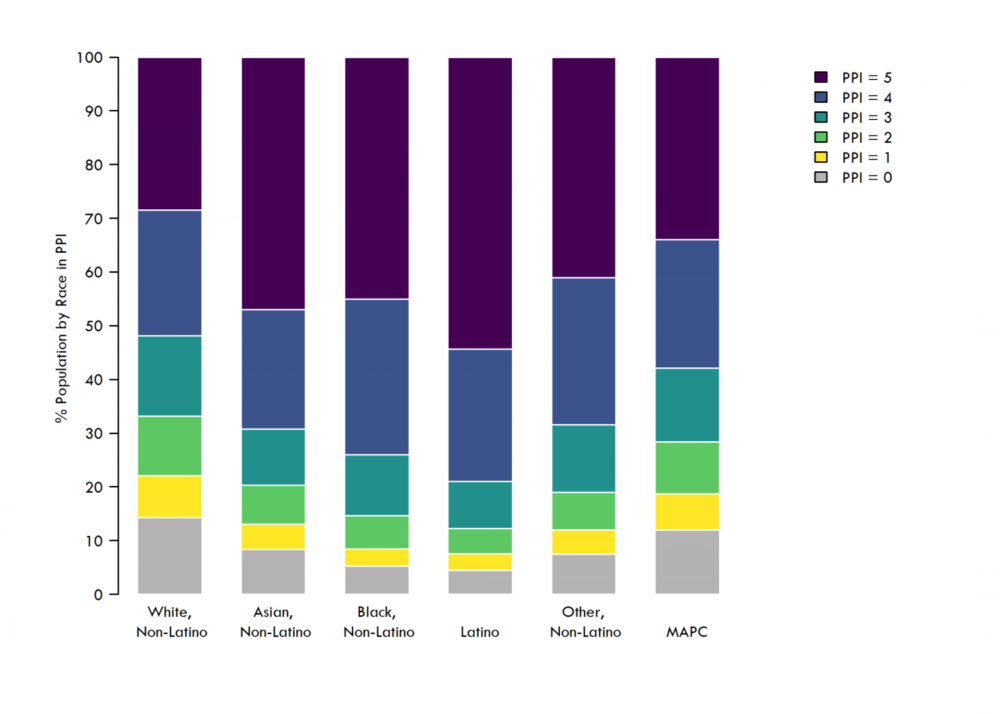

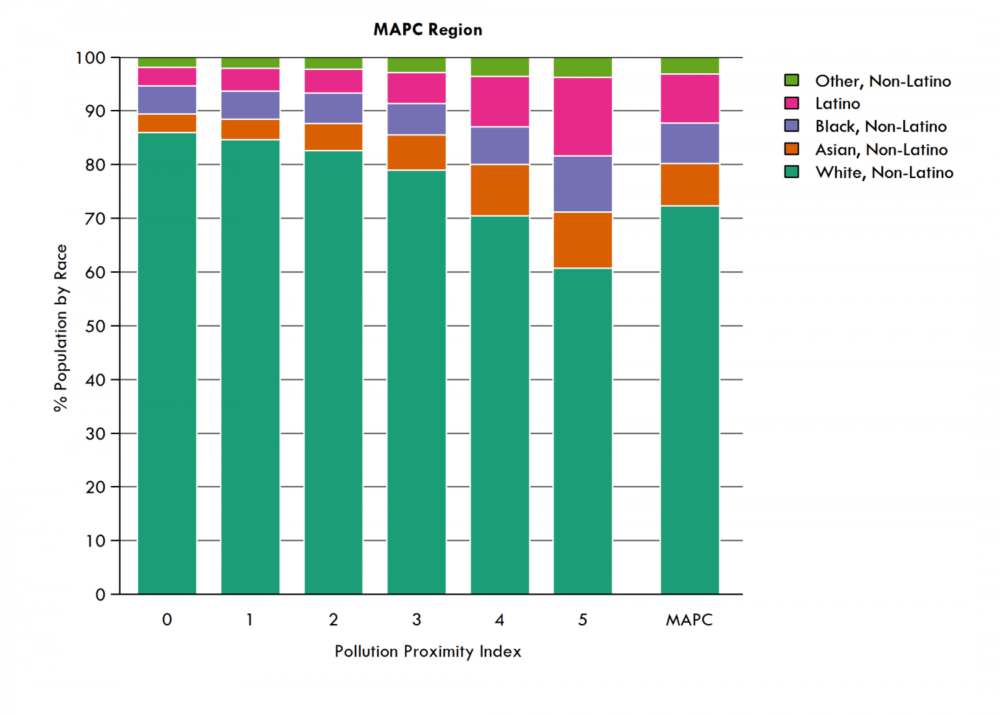

The authors of the study found that 34% of people in the MAPC region live in areas with a high PPI value, but that within that group, there’s a lot of racial disparity. While only 29% of white residents live in high PPI areas, 45% of Black residents, 47% of Asian residents and 54% of Latino residents do.

Put another way, the study concluded that “the relative share of populations of color increases significantly as the pollution proximity increases.” And these trends hold across the region, in both high density and lower density areas.

What’s most important, Gately says, is that these findings are “not merely a quirk of geography.” They exist for a reason.

“The mere fact that pollution is occurring in certain neighborhoods in the region, and that those neighborhoods have people of color in them at a disproportionate rate, is reflective of systemic problems that continue to persist, and the legacy of those problems that continues to persist today,” he says. Examples of those systemic problems include racially discriminatory practices like redlining and blockbusting.

Gately says there are short-term and long-term solutions to the problem. In the near future, cities and towns can consider options like improving the ventilation system in affected homes or building physical barriers to block some of the pollution. And in the longer term, fixing the problem involves both empowering communities of color and redesigning — i.e., greening — our transportation system.

“I think what the COVID-19 crisis and the disparities it revealed really underscores is that we can't wait to solve some of these local inequities,” Gately says. “These disparities aren't going to go away on their own and they need to be actively targeted.”