Advertisement

Mashpee Wampanoag School Looks To Revive Teachings Of Native Language

Resume

In a small classroom in the headquarters of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, children recite words in the language of their ancestors.

The name of the school is Mukayuhsak Weekuw, or "the children's house." There are 13 kids — kindergartners and 3- and 4-year-olds — who began studying when the school opened in September last year.

The school is predicated on the work of Jessie Little Doe Baird, a linguist and member of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe who almost single-handedly saved the language from extinction.

"We speak about them as being sleeping rather than dead because it's a sign of respect for the indigenous languages," says Jennifer Weston, the language program administrator for the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, the nonprofit that runs the Wampanoag immersion school. "The language doesn't really leave, the human community just loses the capacity to appreciate it for periods of time."

Weston adds that the journey to opening the Mukayuhsak Weekuw school was 23 years long. But she puts it into the four-century legacy of British colonialism and the wiping out of Wampanoag culture.

"The overarching goal of the Wôpanâak language reclamation project is to return language home," she says. "So that's a big piece of what we're doing in the school ... the children are literally taking their language home with them and able to teach their family members."

The Mukayuhsak Weekuw school is funded by a three-year grant from the federal Administration for Native Americans. It was originally meant to be a charter school, but Weston said state education officials doubted the school's ability to deliver a curriculum in the language.

Creating that curriculum would not be an easy task, as the last living speaker died more than a century ago. So administrators teamed up with the Montessori Academy of Cape Cod and adopted Montessori teaching methods.

'Learning Their Culture'

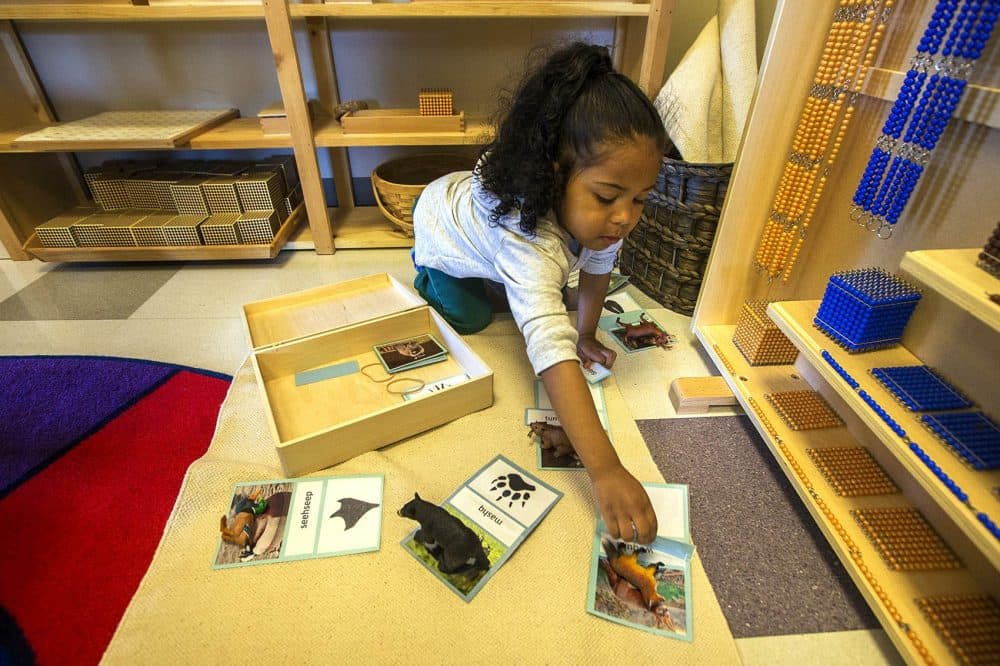

Under the Montessori philosophy children learn in multi-age classrooms to be independent, but also to have a sense of order.

At the tribal headquarters in Mashpee, two teachers are in the classroom at all times speaking strictly in Wôpanâak. The room has a series of stations where kids can hammer nails, wash dishes, and add colored droplets to water.

Visitors to the classroom are asked to use zero English, but the children often revert to English. One of the linguists-in-residence, Tia Pocknett, is playing a language game with one of the kids.

"To have them in this school learning the language, it means that they're learning their culture ... These are the kids that are going to continue these teachings for the next generations to come."

TJ Thomas, parent of children in the school

TJ Thomas works for the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, and he has been bringing two boys in the immersion school. He says he wished he had the same opportunity to learn his tribal language when he was their age.

"I go back to the beginning of when I was a kid, we knew bits and pieces of the language, we knew words, and only years later to find out that most of them were incorrect," he says. "So it wasn't something that we had. We didn't have the opportunity to learn the way they're learning today."

Now, Thomas says, the children are learning not just their language but something even more profound.

"To have them in this school learning the language, it means that they're learning their culture," he says. "They're starting off at such an early age that they're going to be able to pass this on.

"These are the kids that are going to continue these teachings for the next generations to come."

Tribal language leaders see this as just the beginning. They're developing a Wampanoag class in the Mashpee Public Schools, and in the years to come, they want to open an entire elementary school based on the Wampanoag language.

Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this post said there would be 13 children that would begin the program in September. It has been updated to make clear that 13 children began the program last September. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on August 24, 2017.

This segment aired on August 24, 2017.