Advertisement

At MIT, Epstein Report Reopens Wounds — And Prompts Calls For New Leadership

Resume

It’s been a week since MIT released a report that outlined its ties to the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein — and revealed details about an aggressive, often improvised process for accepting financial gifts at the elite institution.

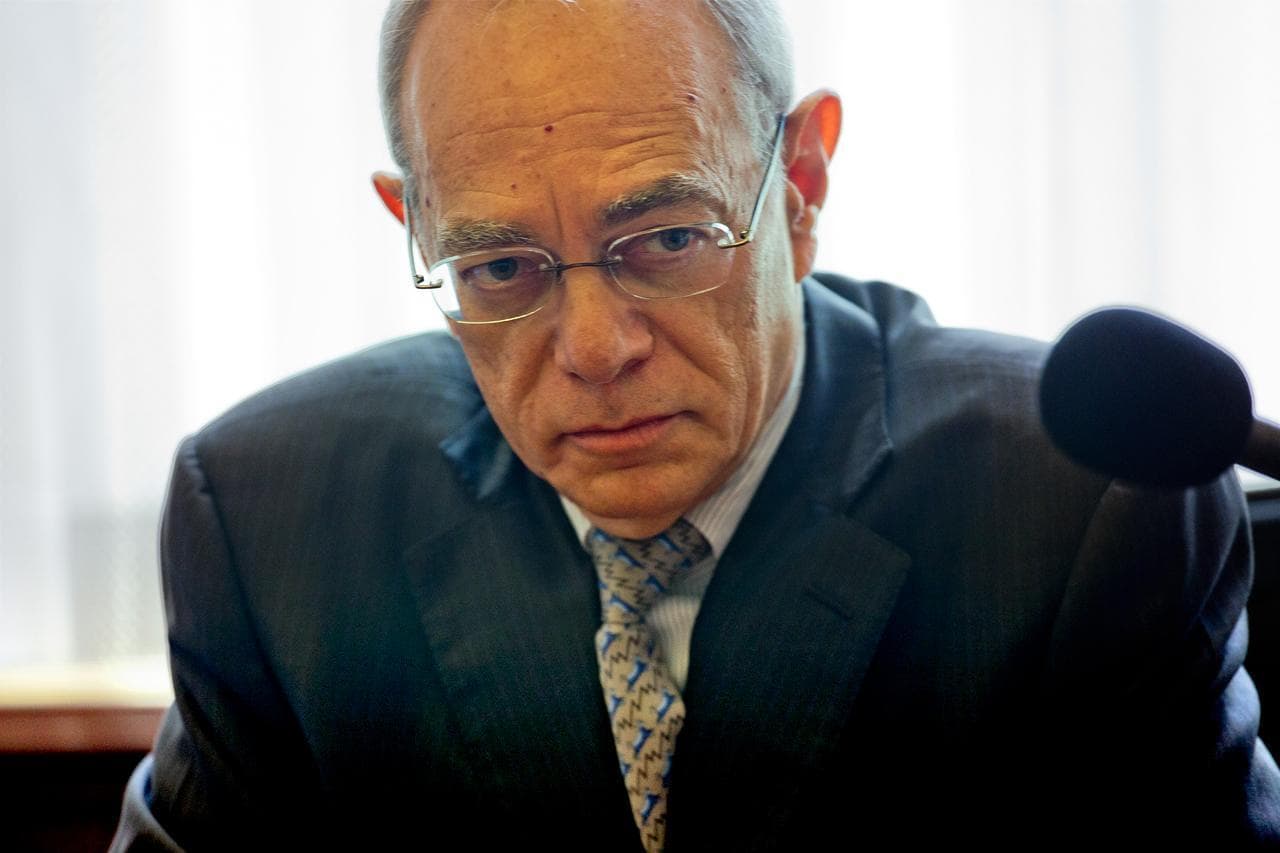

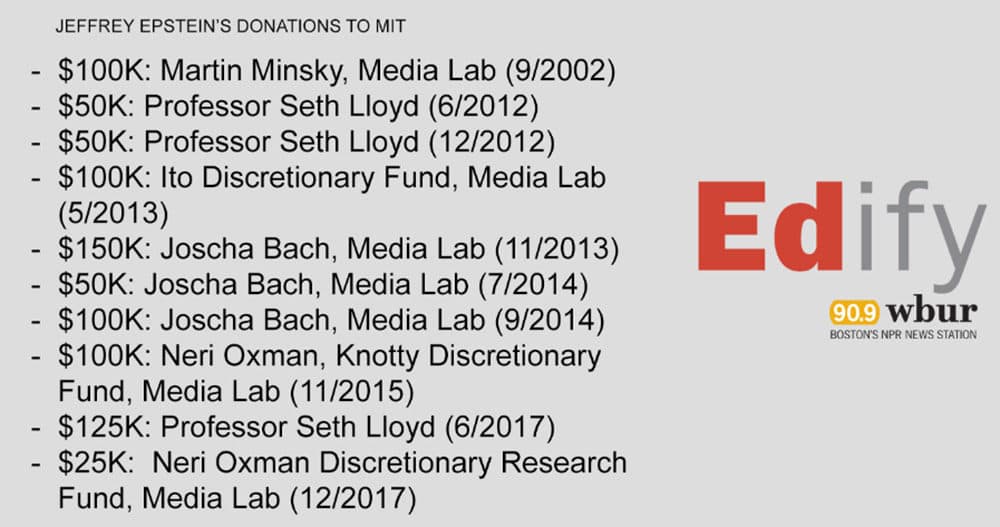

Attorneys at the law firm Goodwin Procter led the investigation, compiling the 61-page report which MIT has published in its entirety. The report concludes that none of the school's current senior administrators — including L. Rafael Reif, MIT's president since 2012 — played a role in accepting the nine gifts Epstein donated after his 2008 conviction in Florida for solicitation of sex with a minor. (Epstein was found dead inside his jail cell last August, where he was being held pending trial on sex trafficking charges.)

As the report is read and discussed, many in the MIT community — including faculty, students and alumni — are raising questions about some of its conclusions and its overall credibility. And some are calling for a change in leadership.

Can Reif Survive?

To the extent that the Goodwin Procter report does find fault with senior administrators at MIT, it focuses on three in particular — none of whom will be part of Reif’s leadership team going forward.

Former MIT general counsel R. Gregory Morgan — whom the report identifies as an especially “significant” force in the decision to accept Epstein’s money — retired in 2018. Former fundraising chief Jeffrey Newton retired in 2013, shortly after a plan to accept small, anonymous gifts from Epstein was agreed upon. Last month, executive vice president Israel Ruiz announced plans to step down in the spring.

The report says that all three men acted “in good faith" in an attempt to balance the need to raise money for research against the “potential damage” the Epstein gifts could cause to MIT’s community and reputation. The report also argues that MIT's lack of a formal policy around controversial gifts forced them "to act on an ad hoc basis."

But it concludes that in doing so, all three administrators committed “significant errors in judgment.” (None of the men responded to requests for comment by the time of publication of this report.)

The Goodwin Procter report does show that Reif signed a formal thank-you note to Epstein in August 2012. It also mentions that Reif wrote “Epstein — Joi Ito” among his personal notes from a meeting in April 2015 — but adds that “Reif could not recall why he made this note.”

Ito, the former head of MIT's Media Lab, stepped down in September after his own ties to Epstein were revealed. In the report, Ito is seen as having pushed administrators — some of them reluctant — to find a way to let Epstein give to Media Lab initiatives.

But many at MIT have expressed doubts that the problem was isolated to Ito and a few retired administrators.

“The final thing was a whitewash,” says Jonathan King, a professor of molecular biology who’s been at MIT since 1970.

King chairs the editorial board of MIT's faculty newsletter, which has become a hub of opposition to some administration decisions. In early 2019, a newsletter editorial called the school's financial ties to the Saudi government "morally unsound, and not in keeping with MIT's mission and culture."

And after the Epstein news broke last fall, the newsletter published an open letter to Reif and others that asked, "How can MIT’s leadership be trusted when it appears that child prostitution and sex trafficking can be ignored in exchange for a financial contribution?" The letter was signed by about 70 women on the institute's faculty.

King believes that it is “impossible” that Reif — who served as provost from 2005 to 2012, and remains deeply involved in fundraising as president — was not aware of the $750,000 in post-conviction gifts from Epstein. As a result, he believes that Reif should step down.

In a letter that accompanied the release of the report last week, Reif apologized for the fact that MIT accepted gifts from Epstein — and visited campus at least nine times — on his watch. “I feel a deep responsibility to repair what is broken," he wrote.

Reif declined to comment for this story — but other faculty spoke up in his defense.

Raul Radovitzky, a professor of aeronautics since 2001, has worked closely with Reif on issues from student life to admissions.

"The notion that he would condone atrocious, abhorrent behavior like accepting money from a pedophile — it's preposterous," Radovitzky says. "It puts into question the people who are going after him."

And in an email, Robert Weinberg, a professor of biology at MIT since 1960, wrote that while he shares some critics' concerns about MIT's direction of late, their focus on Reif is "monumentally unfair." Weinberg says the Epstein incident has become a rallying cry in broader "gender wars" on campus — though, he argues, if Epstein had serially abused young men, the outcome would have been the same.

"Those who accepted Epstein's $$$, I am persuaded, were not blind to how corrosive misogyny has been for our society," Weinberg writes in an email to WBUR. "Instead, they were blinded by the $$$ and thus were willing to turn a blind eye."

But others in the broader MIT community share some faculty's view that the recent revelations around the Epstein scandal require a change in leadership.

In a statement, MIT Students Against War — a group that has organized months of protest around the school's financial ties to Epstein — say details in the report depart from its official summary and show that “Reif, senior MIT administrators, the chairman of the MIT Corporation, Nicholas Negroponte, and countless professors" either met with Epstein or were aware he was trying to donate to the school.

At a rally attended by hundreds of students and neighbors in September, the group called for Reif to resign, and they are renewing those calls in light of the Goodwin Proctor report.

Cambridge city councilor Quinton Zondervan, who earned a master’s degree from MIT in 1995, says that it is possible that Reif was unaware of the gifts. But he adds that if true, that in itself would be cause for concern.

Zondervan says he has found that fostering a culture of transparency and candor is an essential part of leadership: "I make it very clear, from day one, that [my staff] need to tell me absolutely everything -- especially if it's problematic."

For failing to build such a culture, Zondervan believes Reif should resign — and that Cambridge city government has a role to play in the institute's reform. "Imagine how different MIT's behavior would be if they had to disclose their major donors" to the public, for example, he says.

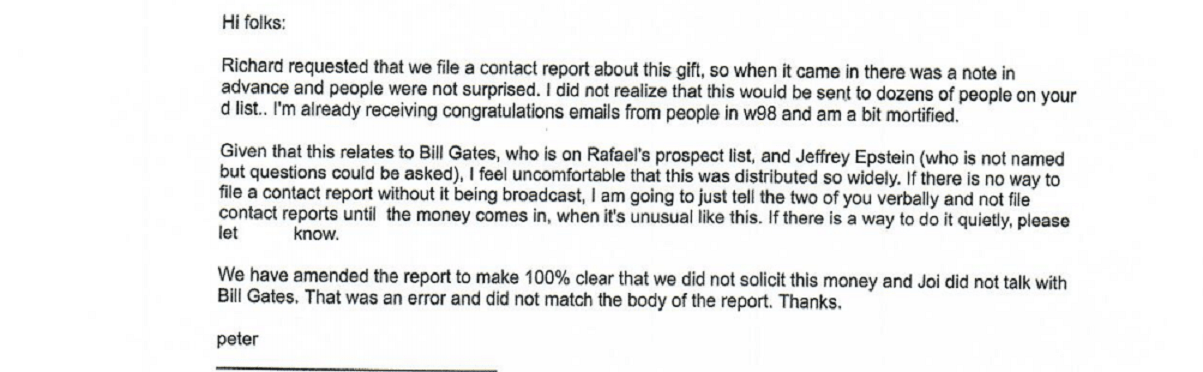

There is some evidence that top staff at MIT’s Media Lab acted to limit wider knowledge among staff of Epstein’s gifts — including among emails obtained from Whistleblower Aid, a legal organization that defends individuals who report illegal activity inside institutions.

For example, in a 2014 email, Peter Cohen, then the Media Lab’s director of development, describes himself as “a bit mortified” that an incoming $2 million donation from Bill Gates — allegedly facilitated by Epstein — was announced by a mass email to dozens of other fundraisers. Under university policy, MIT’s fundraising contacts with Gates were set to be handled by Reif himself. But after the mass email, Cohen asked a colleague in development for a way to accept such gifts “quietly” going forward.

Gates has denied that his gift was in any way connected to Epstein.

In response to the Goodwin Procter report, the executive committee of the MIT Corporation has released recommendations for Reif, including the development of clear policies to inform decisions around controversial donors, a culture of “accepted … whistleblowing,” and support for the Media Lab, which is still reeling from Ito’s sudden resignation in September.

The Report's Credibility

Many, too, harbor concerns about the Goodwin Procter report itself.

Last September, Reif announced the large law firm, which has represented MIT in a number of high-profile cases, would be hired to conduct the investigation. King calls that a “very deep conflict of interest.”

“[Investigators hired] by the person who might be the actual perpetrator of the problem?” King says. "At another university — any place that has a law school — you wouldn’t be able to get away with it.”

Shortly after Goodwin Procter began the Epstein review, the executive committee of the MIT Corporation retained attorneys from a second firm, Paul Weiss, to review Goodwin Procter's findings.

Goodwin Procter has represented the institute in several high-profile cases since 2010. A statement on MIT's website says that experience allowed Goodwin Procter attorneys "to get up to speed quickly," while Paul Weiss was chosen for its "independence." In the end, the Paul Weiss attorneys concur with the report's conclusions.

Others at MIT are taking issue with the report's specific claims. For instance, the report asserts Seth Lloyd, a professor of physics and mechanical engineering, “knowingly facilitated Epstein’s plan to circumvent any possible MIT vetting process” as he accepted $250,000 in gifts beginning in 2012.

In a post shared on Medium Friday, Lloyd called that assertion “completely false,” sharing what he claims are emails from an MIT development officer welcoming the gifts. (Lloyd has apologized for his relationship with Epstein, and was recently placed on paid leave.)

Others complain of apparent carelessness in the report’s composition. Judith Donath — a longtime Media Lab researcher now at Harvard — says that within an hour of the report’s publication, she got a message from her eldest child, an MIT alum, “saying, ‘Mom, do you know you’re in this report?’ ”

The report says Donath and other scholars were present for a meeting with Epstein on Oct. 23, 2013. Donath says that never happened — and that she never met Epstein in person at all. She shared an email with WBUR showing that while her name was mentioned in a follow-up email about Epstein's visit, she and two other colleagues were not at the meeting.

Donath and the others asked Goodwin Procter to correct that sentence based on the evidence available, but that the change was not made when she was told to expect it. For Donath, the incident demonstrates “a disturbing disregard for facts” — at a moment when clarity and care is needed.

Roberto Braceras, the first-named author of the report, declined to comment for this story. On Jan. 17, MIT shared a corrected report from Goodwin Procter, from which Donath's name was removed.

In a comment relayed by MIT's news office, Goodwin Procter declined to make a similar change to reflect Lloyd's complaints, writing: "To the extent Professor Lloyd disagrees with the Report, we are fully confident the findings in the Report are consistent with the evidence and information that we collected, including from Professor Lloyd.”

An Institute 'Out Of Whack'?

Whether or not the details of the report are strictly accurate, many people spoke to a sense that the institution it describes has recently lost its way.

On Wednesday, MIT’s faculty newsletter took the unprecedented step of pre-publishing an article called “MIT: Where Now?”

As co-written by two veteran faculty members, Leigh Royden and Rosalind Williams, the article is based on hours of independent interviews with 11 other veteran faculty members, all of whom remained anonymous. Williams says the near-consensus of those they interviewed is that the Epstein controversy is just the latest manifestation of a long-running crisis.

From 2010 to 2019, MIT’s endowment more than doubled; it’s now valued at more than $17.4 billion. And the institute has nearly succeeded in its mission to raise $6 billion in new capital, as announced by Reif in 2016.

Williams says she was "really surprised — at the depth and breadth of the unhappiness." Many faculty, she says, are worried about the costs of such rapid growth. In the article, interviewees claim that “donors are setting the agenda,” and that “money drives everything” at MIT.

“The tension of mission and money-raising is eternal at any institution,” says Williams — and especially at highly “practical” MIT. But for most of her interviewees, Williams says, it seems that “the balance has come out of whack” in recent years, weakening the school's ethics.

Alonso Espinosa Dominguez — a senior studying mathematics and an organizer with Students Against War — agrees, saying the Goodwin Procter report seems at times to take for granted that when considering gifts from sources like Epstein, "reputation concerns" should be the principal cause for hesitation.

“Epstein got away with serially trafficking women and girls because he had powerful friends,” Espinosa Dominguez says. “That should be the main issue here.”

MIT is not the only prestigious local institution where Epstein wielded money and formed relationships. Epstein gave more than 10 times as much money to Harvard as to MIT — around $8.9 million, according to a September 2019 letter from Harvard president Lawrence Bacow. Unlike MIT, Harvard has not had a public debate about Epstein's ties on campus, but an internal review is ongoing. Jonathan Swain, a Harvard spokesman, says that all of Epstein's gifts came before he went to trial for soliciting underage sex in 2007.

“Epstein got away with serially trafficking women and girls because he had powerful friends. That should be the main issue here.”

Alonso Espinosa Dominguez

Many faculty and student activists say they agree with the report's conclusion that MIT needs a formal policy to handle “controversial donors." (A 2013 email from chief fundraiser Jeff Newton makes reference to an apparently informal "system" for examining donors' backgrounds.) But many also say such a policy should have been developed long before the Epstein controversy exploded.

For example, King says “every sector” of the MIT community was opposed to Reif’s decision to accept contributions — and a March 2018 visit — from Mohammad bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, as Saudi forces were expanding the devastating war in Yemen. Faced with a wave of faculty statements, student editorials and more, King says, Reif and his senior team “completely ignored it."

An internal review concluded that funding from Saudi sources accounted for 0.2% of MIT’s annual operating budget and recommended against severing those ties.

Professor Raul Radovitzky, for his part, warns against making connections between the specifics of the Epstein incident and MIT's history of research relationships with private industry and government. "At that point, you need to look at the whole thing," Radovitzky says — "at MIT and its very existence."

Now two separate committees at MIT are working to develop “a set of values and principles to guide the assessment of outside engagements” as well as review its specific policy regarding gifts, according to a release by the institute’s news office.

MIT might consider an "ethical fundraising" policy, according to Noah Drezner, who studies philanthropy in higher education at Columbia’s Teachers College. Such a policy would clearly outline who fundraisers will and won’t accept gifts from, based on the institution's values. For example, Drezner says, some institutions avoid funding from firearms manufacturers, tobacco companies or fossil fuel companies.

But that is complicated work at an institute where controversial research partnerships date back to the Manhattan Project and beyond. More recently, the late David Koch — whose fortune came from fossil fuels, and who spent millions more sowing doubt about climate change -- gave $134 million to MIT (his alma mater) during his lifetime, most of it for cancer research.

Drezner acknowledges fundraising issues are complex — but he adds that “transparency is extraordinarily important.” If anonymous gifts are a necessary feature of big-time philanthropy, he says, the practice on display in the leaked emails and the Goodwin Procter report — of “keeping things quiet,” and sharing details sparsely — should be abandoned if MIT hopes to move forward under Reif and the present team.

This segment aired on January 21, 2020.