Advertisement

In Their Own Words: Three Autistic Redditors On Autism

TL;DL (Too Long; Didn’t Listen)

Three autistic Redditors talk to us about their view of the world, their view of autism, and their hopes for greater representation in society.

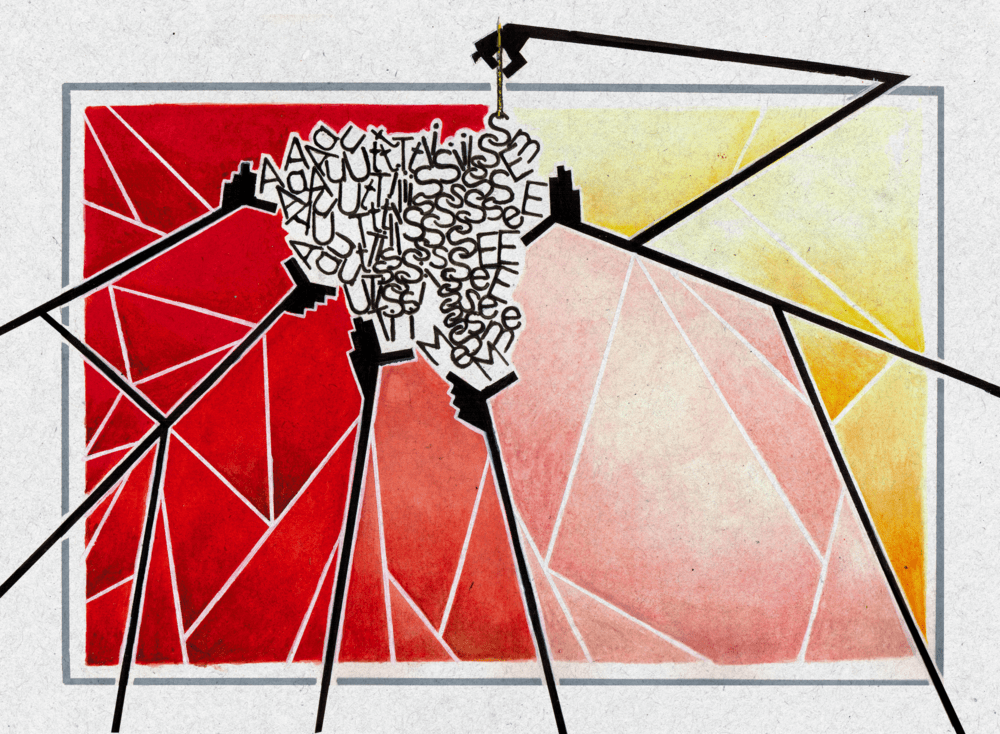

Thanks to Martin Kronström for this week's artwork. It's called "Autisme." You can find more of his work on his website.

Links:

-r/Autism

-r/AutisticPride, the subreddit that Nick created

-Endless Thread's post in r/Autism calling for participants in this episode

-Jess's blog, "By Autistics, For Autistics"

Contact Us:

We want to hear from you! Don't hesitate to reach out with reactions to episodes, ideas for future stories, feedback about the show, or just to say hi. There are a few ways to reach us:

- Post or comment in the official Endless Thread subreddit

- Send us a direct message on Reddit. Our username is endless_thread

- Email us at endlessthread@wbur.org

- Leave us a voicemail at 857-244-0338

Full Transcript:

This content was originally created for audio. The transcript has been edited from our original script for clarity. Heads up that some elements (i.e. music, sound effects, tone) are harder to translate to text.

Ben Brock Johnson: Amory, obviously your favorite set of movies that include the word star in the title are every single version of the film A Star is Born?

Amory Sivertson: We saw this movie together. I hated it.

Ben: We love Gaga, though. So don’t get it twisted.

Amory: No. But no, you know the answer to this. It’s Star Wars, always and forever.

Ben: But the prequels were better, right?

Amory: Now you just want me to kill you with fire. Right into the sun!

Ben: I’m just kidding. I do not believe that the prequels were better. But I do want to introduce a guy from New Mexico, who’s probably also a Star Wars fan?

Advertisement

Nick Bevins: If it has the word star in the title I have seen it three times.

Ben: This is Nick Bevins. Or, as he’s called on Reddit…

Nick: Orbital Colony. The meta commentary there is that being autistic, sometimes it can feel that you're apart from this society and, an outside observer.

Ben: Do you have any favorite space themed science fiction?

Nick: Oh, don't get me started.

Amory: OK we won’t. So let’s talk about something else Nick feels strongly about — the language around autism. Nick is autistic.

Ben: Which is, the way that Nick wants us to say that. Not a person who has autism.

Ben: Can you just talk about the difference in semantics there for us?

Nick: What we currently have as our understanding around autistic people is a medical diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. I disagree with that categorization. I don't agree with pathologizing an entire segment of the population, especially when there's nothing wrong with that segment of the population. So, to me, saying “person with autism” would be like calling a gay man a person with homosexuality.

Ben: This is not everyone’s perspective. But it is eye-opening. I don’t know that I’ve ever thought too deeply about how autistic people think about autism. Or even talk about it with each other.

Amory: Me neither. But we’ve both been thinking about this a lot more since we discovered that there’s a really large constellation of communities talking about autism on Reddit. There’s Autism, Autistic, Autism Acceptance, Autism Translated, Autism Parenting, Aspergers, AsperGirls. There’s also Autistic Pride. That last one was started by Nick.

Nick: The internet in general is an amplifying tool. And it's amplifying in two aspects. One, is you are reaching from just your community to across the world. But the other amplifying effect is that most autistic people are in the closet. So if you can go on Reddit and be anonymous, then there's no fear of being outed, there's no fear of repercussions in your workplace, there's no fear of repercussions in your personal life.

(music plays)

Ben: We set out to make an episode that looks at this conversation happening online. And the more that we talked to people for this episode, the more we got a sense of the vast spectrum of autism and autistic people, people with autism, people who are neurodiverse, however you prefer to describe it.

Amory: So it’s a good time for us to talk about this. Or maybe, it’s a good time for us to listen.

Greta Thunberg: I think in many ways that we autistic are the normal ones. And the rest of the people are pretty strange. Especially when it comes to the sustainability crisis. Where everyone keeps saying climate change is an existential threat and the most important issue of all. And yet, they just carry on like before.

Ben: That’s Time Magazine’s 2019 person of the year. Climate activist Greta Thunberg. Doing a TED Talk.

Amory: So today, Ben and I are going to listen. And other than us, you’re only going to hear autistic voices. Three of them. People with different experiences and different perspectives.

Ben: You’re going to hear about their lives, how they think about autism. And how they think about the world. That’s it. Today’s episode…

Ben and Amory: Nick, Jess, and David.

(music plays)

Ben: I'm Ben Brock Johnson.

Amory: I'm Amory Sivertson. And you're listening to Endless Thread.

Ben: The show featuring stories from the vast ecosystem of online communities called Reddit.

Amory: We're coming to you from WBUR, Boston's NPR station. We’re not sure what causes autism. It’s usually defined as a developmental disorder characterized by a range of behavioral challenges. Lack of social skills, repetitive behaviors, and difficulty with speech, among others. Autism is referred to as a spectrum of these behaviors. Because it manifests differently in every autistic person.

Ben: Most people talk about this spectrum as a straight line — with people who can more easily function in “normal society” on one end, and people who can’t, on the other. Historically, “high-functioning” autistic people were even given a separate diagnosis: Asperger’s. Today, all autistic people get the same diagnosis: Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Amory: Nick, who we’ve been hearing from, describes the spectrum as being less like a line and more like a circle — people exhibit certain autistic traits more than others, but those same people may exhibit other traits less. So it’s not quite as linear as most people think.

Ben: And Nick’s participating in an ongoing debate within the autistic community online about whether autism should even be viewed as a disorder in the first place.

Amory: He doesn’t like the implications of that term. Because he says the only thing that’s disabling about autism is the way society is set up.

Nick: If 99.999% of the population was born without legs that, you know, worked and they were in wheelchairs. And then you were born with legs that function, you would be considered disabled because the entire society would have been constructed for people who use wheelchairs.

(music plays)

Amory: Now, Nick is speaking from his experience. There are a lot of autistic people out there who have debilitating physical, social and emotional challenges. People who can’t speak for themselves. Members of their families sometimes can.

Ben: This is in some ways a familiar narrative. Disabled. Victims of disease. Unable to speak for themselves. Nick wants to change that narrative, or replace it.

Amory: Replace it with something that’s more inclusive to all autistic people. To Nick, being autistic isn’t a disability. It’s a different way of moving through the world. And that shouldn’t be considered a bad thing.

Nick: I see the autistic community of the same place that the LGBT community was at in the 1960s and 70s, where if you were gay, you were diagnosed with sexual orientation disturbance. It was a medical diagnosis. That was the conventional wisdom within the medical community, that because you were different, you were acting outside of societal norms, there must be something wrong with you. So right now, we're being diagnosed — I am officially diagnosed — with Autism Spectrum Disorder. We have applied behavioral therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, which is just conversion therapy by a different name, where we go in there and they train you to repress certain autistic traits to have you come across as normal, whether that is avoiding eye contact, training children to maintain eye contact, when there is nothing inherently correct about that behavior, where in other cultures it is considered rude to look people in the eye. So they are enforcing a cultural norm.

Ben: When cultural norms get enforced, things or people who are seen as abnormal, get unwanted attention.

Nick: Whether it is the bullying that's going on in school. Up until quite recently, actually, the common insult was to call someone gay, to call anything gay. If you were insulting it, that's so gay! When I was growing up in school, that had begun to change as we have begun to accept the LGBT community and their right to exist in society as they are. When I was going through school, we started to see the trend of people describing things as autistic: that is so autistic! You know, you're fucking autistic. I'm sorry for the language there, but that is the kind of, you know, attacks we receive. We're going through a lot of the same stages that the LGBT community went through. And that's why I'm trying to emulate their success in my subreddit, r/autisticpride, because I think we are seeing a lot of the same patterns within our communities.

Amory: As we’ve said, this is not the perspective of everyone. But it’s the focus of Nick’s activism. And in a very straightforward way, he’s advocating mostly for society to stop pigeonholing neurodiverse people, stop treating them as one kind of person.

Nick: You know, that's why Greta Thunberg is such a game changer for us. Because before Greta, what we've all had the experience of being compared to is Sheldon from the Big Bang Theory. You know, there is a positive aspect to that, that Sheldon is a genius of geniuses, right. But he's also an egotistical, emotionless, narcissistic robot, you know, who could care less about how other people feel.

(A scene from Big Bang Theory plays)

Sheldon : I realized I can go to your aunt’s awful party and still spend the whole day gaming with my friends.

Amy: Sheldon, my relatives are gonna wanna talk to you. And you’re going to be sitting there playing a game? Isn’t that a little rude?

Sheldon: Oh, I’ve got that covered. Headset. I won’t hear a word the old geezers are saying...

Amory: Nick wants the representation of autistic people to move beyond the Sheldon caricature. And towards people like Greta Thunberg. That’s why Nick is planning to run for local office in 2021. He’d be the first openly autistic politician in New Mexico. And he hopes that’s just the beginning.

Nick: Seeing somebody on the national stage or international stage, a public figure who you can identify with, it shatters the stigma. It shatters, it cuts through more than anything else the stigma and the stereotypes and the self-hatred that so many of us carry around.

(music plays)

Ben: The history of autism is complicated. The most famous pioneer of autism research was an acclaimed Austrian doctor named Hans Asperger, who was active back in the 1930s and 1940s.

Amory: It turns out, Asperger was pretty cozy with the Nazis. They helped further his career, and, in return, Asperger supported Nazi programs that have since been completely rejected, of course. Things like forced sterilization and even a child euthanasia program.

Ben: Asperger’s autism research wasn’t widely adopted until the 1980s, and there’s been tons of autism study in recent decades that has nothing to do with this. But Asperger’s ideas became the foundation for how modern society came to understand these types of behavioral “disorders,” Nazi associations be damned.

Amory: And his ideas were pretty harsh in their own right. “Autistic psychopath” was the term he first used to identify children with autistic characteristics. And the scope of his research was narrow.

Jess: He only studied like young white boys and he like, you know, they were like extreme examples of people who are autistic because, you know, like that's the people who are obvious. So then, you know, when someone like me comes along, they're like, oh, no way you’re autistic because you don’t, you can do this, this and this and all that.

Ben: This is Jess.

Jess: I’m 17. I live in Miami, Florida. And I'm autistic.

Amory: According to data published by the “American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,” four boys are diagnosed with autism for every one girl.

Ben: The lead investigator from that study says the evidence for that disparity points towards diagnostic bias, suggesting that girls are under-diagnosed for autism. Jess’s own experience backs this up.

Amory: She was misdiagnosed for years. At first, she was told she had something called “Oppositional Defiant Disorder.”

Jess: It's basically a disorder for people who like act out for the sake of acting out. I guess they thought I was doing it to be disobedient where like, in my head, if I break a rule, I'm like, oh, just just take me to Alcatraz, like for breaking this small, unimportant rule. So they were way off base.

Ben: We did not find Jess on Alcatraz. We found her, on the internet. Where she spends a lot of time.

(music plays)

Jess: One of my special skills is having the maximum amount of tabs open at once. I have a t-shirt and I think it says something like, “My mind is like an internet browser. I have too many tabs open. One of them is frozen and I have no idea where the music is coming from.”

Ben: (laughter) That's a good shirt!

Amory: There’s a good chance at any given time that at least one of Jess’s internet tabs is open to Reddit. Specifically, to one of the many Reddit communities created by and for autistic people.

Jess: We all know we’re autistic so we can talk about other stuff, although we do talk about being autistic a lot. And, you know, how life is very difficult, but like, you get through it together.

Ben: When we put out an open call on Reddit for participants in this episode, Jess responded enthusiastically. Among other things, she wrote, “I like being autistic, and would not quote ‘cure’ myself if I could.”

Amory: Jess always knew something was up.

Jess: The first day of school when they pass out the syllabus, it was like I'd like missed that, but for life. Like, OK, here's the syllabus for how to talk to people and like, you know, playdates and all that. But like, you know, couldn't get the assignment from anybody, to extend the metaphor.

Ben: Jess started out at a Waldorf school, so she didn’t need a “life syllabus” at first. Her school had lots of recess, a nontraditional curriculum, her differences were celebrated!

Amory: It was when she moved to a traditional school in fourth grade that she started having problems.

Jess: Not with like the work itself, like, not to toot my own horn but I am like, of course, a genius. But like with just like being organized and stuff like my executive functioning is so bad.

Ben: Homework and deadlines and a whole new group of classmates who already knew one another, that would be daunting for anyone. But they were extra challenging for Jess.

Amory: Meanwhile, consults and testing with many different doctors led to conflicting answers for Jess and her parents, Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Anxiety.

Jess: I think some doctors had actually been like, “She can’t be autistic. She makes eye contact, she can talk to people, blah blah blah.”

Ben: Finally, when Jess was 13, a doctor officially put autism on the table. But after so many misdiagnoses, her parents wanted to be absolutely sure before telling Jess. So they sent her to a renowned therapy program in Utah to confirm the diagnosis. A few months later, Jess’s parents delivered the news.

(music plays)

Jess: I was in Utah sitting in a food court eating Panda Express. My parents were going to take me to a therapeutic boarding school and they're like, “Oh, and you're autistic.” And I was like, “Oh, cool, that makes sense.” And then I kept eating my Panda Express. I was very young.

Amory: What did it feel like to be told that?

Jess: It was, I mean, in the moment, I was like kind of focused on my Panda Express because like, I hadn't eaten anything like that in like 10 weeks. But like, yeah, it's definitely nice having the diagnosis because like, you know, not having it wouldn't mean I'm not autistic. It just means now I have a name for the stuff I go through. It's not all like rainbows and sunshine, but like, you know, I would still be it without the name. So might as well have a name for it.

Amory: Jess spent the next year and a half attending a boarding school in Utah specifically geared towards autistic teenage girls.

Ben: Meeting other autistic people — whether at boarding school or online — has been an important way for Jess to feel seen.

Jess: The most famous autistic character I can think of is Sheldon Cooper from the Big Bang Theory.

(more Big Bang Theory plays)

Sheldon: You don’t think I’m condescending, do you?

Penny: Well…

Sheldon: Oh, I’m sorry, condescending means--

Penny: I know what it means!

Jess: He is a jerk. Also, what’s even better is the show officially has been like, “He is not autistic! He is just whatever.” But like, you know, he's very clearly like a, he's basically a caricature! And I'm just like, one, I'm not a jerk. Two, I'm not like a 30-year-old white guy. And three, just like, really?

Amory: Jess actually wants to correct this. She wants to write a comic book featuring characters who feel more true to her.

Jess: So like the main character would be this autistic person and like, they're like shape shifter and they like shape shift until like, you know, a normal human to, like, fit in. Stuff like that.

Ben: Jess has no shortage of ideas. But it may be awhile before she’s able to turn those ideas into comic book gold. Starting this past February, she’s been busy dealing with something more urgent.

Jess: I started having to wear sunglasses all the time, like even at night, because my eyes were just really sensitive.

Amory: Jess has always been extra sensitive to sound and light. But this is next level.

Jess: I had to like spend the week in my room because, like, I literally, like I think I was wearing like my sunglasses under the covers. I just could not deal with light. It was really bizarre.

Ben: Jess’s condition has improved slightly since then. She can come out of her room, but she’s still having migraines. And she’s not yet well enough to go to school. She was in her room when we called her. And she was wearing her usual attire.

Jess: Well, you know, in keeping with the latest trends I have on not one but two pairs of sunglasses. And then over that I wear a hoodie and then over that I wear like a beach hat to block light from all angles. It's the latest fashion in case you didn’t know.

Amory: Doctors aren’t exactly sure why this is happening to Jess. They think it has something to do with the levels of antibodies in her blood. It’s unclear if it’s directly related to autism. But sensory sensitivity is a familiar experience for a lot of autistic people.

Ben: Spending the day stuck in your room with two sets of sunglasses on might make anyone feel like a bit of a martian. But something that makes Jess feel like a regular teenager, is talking with her autistic friends. Recently, they’ve been talking about a new project.

Jess: We wanted to do something to like, you know, fight the fight and make our voices heard and all that. It's a fun thing.

Amory: At first, they thought about doing a podcast. Naturally.

Jess: That's the popular thing the cool kids are doing. And then we realized doing a podcast is hard. And I was like, I remember I was just like, “Do you want to do this?” And she was like, “No.” I was like, “How about a blog?” And she was like, “Yeah.” And then we did the blog.

Ben: Thank you for saying that podcasts are hard.

Jess: God, it's ridiculous. Like with the audio, the files and the ugh, yeah.

Ben: The audio and those files will get you every time.

Amory: Every time. Jess’s blog is called “B-A-Four-A” or “By Autistics, For Autistics.” She’s written about her love for internet research, common myths about autism — even that moment at Panda Express when she learned she was autistic.

Ben: She’s also written a poem about a birthday party she went to when she was 10.

Jess: That birthday party was a time I, like, freaked out. It's like a good example of like, you know, the sorts of meltdowns I used to have. It's kind of a traumatic memory. And what is a poet to do with trauma but turn it into a kick-ass poem?!

Amory: Here’s a snippet of that kick-ass poem (full poem here):

Jess: The cool house with the zip line has a yard growing, screaming children. My radar instruments pierce every time their shrieks pass 90 decibels. A water bomb is thrown. It explodes me. Launches me up into a tree. Legs and arms and melted eyes now lawn ornaments all alongside goggles, crushed cupcakes, children. I was not expecting to be hit with a bomb. Hydraulics open. I'm sobbing now. A rich, ripe leaf is ripped right off and smeared across to smear my snottings. Class acquaintances and parents dodge the snotty spectacle dropped underneath. Dad arrives, calls out to me, “Fall out of the tree! I'll catch you in your towel.” Still dry, I fall. The towel scrapes me up a bit. Towel burn. Nothing too bad. No worse than my diagnosis. Heartbreak. Home now. Gorilla glue. Vines. Boxes. Boxes and boxes of books, sand, string. The next few hours are busy. I spend them using my box of goods, congealing all of my parts, all together.

(music plays)

Ben: Jess says she knows she’ll continue to face challenges throughout her life. But she’s another person who has started to speak out about it. Because if there is a statement we can make that is true for both Nick the activist and Jess the poet, it might be how they want to be seen.

Jess: I want people to know I'm autistic. But also I don't want to be like, oh, you're the autistic person. I want to be like, oh, you are a person, you're autistic. But like, you're a person and just sort of not have it be like a huge deal. And like, online, unless I bring it up, it's not a huge deal.

Ben: Well, Jess, thank you so much for your time and for talking to us. And I really look forward to reading your comic book about Autistic Super Heroes Day.

Jess: Dang it, now I have like an obligation to do it. Why!?

Ben: Yeah, first draft is due whenever.

Amory: We won't make you make a podcast, but we would like to read that comic book.

Jess: Oh good. Here I was thinking you guys were heartless, but you know you're not making me do a podcast, so...

Amory: Just a comic book.

Jess: Just a comic book.

(music plays)

Amory: We'll be back, in a minute.

[Sponsor Break]

Ben: Quick heads up. There’s some mention of physical abuse in this next story. There’s also something our next guest references that we should define, just so it makes sense: self stim. Which stands for self-stimulation, it’s a repeated, often physical action that is associated with some people on the autism spectrum.

Amory: So we’ve been hearing from two people who found out they were autistic pretty early in their lives. Now we’re going to hear from someone who didn’t. Even though there were hints early on.

David William Chin: I remember when I was in the fourth grade, we were playing marbles during recess and this one kid tried taking my marble and I said, “What are you doing?” He said, “I won.” I said, “But we were practicing. You know, we didn't say it was for keepsies.” So he told me to go jump in a lake. It was really hot and humid and jumping in the lake actually sounded quite refreshing, but I did point out that we did not, I was not aware of any lake near of a school. I had not brought my bathing suit. And so when I went home. We had, there was a swimming pool. So I jumped in the swimming pool, clothing and all. My mom was on the balcony waiting for me to come back. And um, it's never good when a parent uses your entire name: “David William Chin, get out of that pool!” So, you know, “Yeah mom, OK.”

(music plays)

David: I'm David William Chin. I'm 59 years old. I'm a culinary arts teacher in Nevada. I tend to have a very literal mindset, so. That does create. It's and it still does. It still creates problems for me. From time the time I have problems. I still have problems with sarcasm. I wasn't diagnosed until later in life. So my parents had pretty strict expectations as to how I would behave and what I would learn and what I would do with extracurricular activities. And, you know, if it had been up to me, I would have loved being left alone in my room. And they said, no, no, you have to you know, you have to join the scouts and you have to learn how to ride a horse. And you have to take Red Cross lifeguard lessons and you have to learn how to play the piano. And they made me go out and participate and I hated it. But in doing this, I also learned how to interact with people. I learned how to be part of a team. I learned how to take turns. I learned how to follow the rules. And I did not enjoy the process, but I do think I'm the better for it. Back in the 60s, you did not take your kid to see the shrink. It just was not done. So, if I started trying to self-stim for me, that was I like shaking my head violently. And I would flap my arms a lot. And my dad would give me a warning and say, stop it. And if I didn't heed him, he'd pull off his belt and lay into me or my mom would pull out her yardstick and go after me. Back then, it was called tough parenting. Adverse behavioral conditioning. Nowadays, we might call it child abuse. But yeah, I learned I learned to internalize a lot of the, you know, this twitching.

Amory: As you grew up and, you know, became your own person and went off to college and got a job. How did some of these challenges stay with you or how were they different as you were gaining some independence?

David: I still struggle with relationships. The time and effort to invest in a relationship or a friendship is is emotionally exhausting.I did not realize I was autistic until I self diagnosed when I was 54. And then I got a clinical diagnosis when I was 55. But prior to that, you know, I tried hard. I tried to have friends and to have a normal life to, you know, to court a woman and to date and, you know, maybe get married and, you know, do the family thing with the kids. And no matter how hard I tried, I just could not. I never had many friends. My relationships have been far and few between. Usually not ending very well. And I just could not figure out what I was doing wrong.

Ben: Can you talk about the most recent relationship and sort what that experience was like and how it ended?

David: So I was with someone online through Our Time, which is geared towards people who are 50 and older. And I met someone and we hit it off and she said, “I really like you, but I want you to know that I was in an abusive relationship and I just want to be friends. And so let's be friends for a year.” And I said, “OK.” I love parameters! Parameters are great because parameters define the boundaries within which I can interact. You know, being friends for a year? I could handle that. And and it was nice. And then and then I started noticing that when we're sitting on the sofa. She's leaning against me. And I thought, well, she's just tired because, you know, she's a friend. According to the friendship paradigm. There's no hanky panky because we had a friendship agreement for a year. So then she started, she would touch me and, you know, run her fingers down my arm. And at one point she she disappeared into the bedroom and she called my name. So I went and she's lying on the bed and she was smiling at me and she had her arms out towards me and she said, can you tell what I'm thinking? And I thought, well, no. Because we had a friendship agreement, so, therefore, it could not be anything amorous. She must be tired. So I apologized for having intruded upon her time. And I left. And the next thing I know, I'm being texted that she never wants to see me again. So, um, a friend told me that she was upset because I had rejected her and that I should apologize. And I said I have nothing to apologize for. I did not violate the friendship agreement. And since I do have a literal mindset, I did not see her again.

Amory: Did you ever try contacting her again to explain…

David: No she said she never wanted to see me again.

Amory: But did you ever think that maybe you could explain to her the misunderstanding that happened?

David: No. Because she said she never wanted to see me again. Plus she also--

Ben: Yeah it’s against the rules.

David: I had a cousin explained to me that that, you know, that she may not actually have meant that, but that's what she said.

Amory: Yeah.

David: And so I've honored our agreement. And I I also respected her wishes. And I can't be anyone other than the person I am.

(music plays)

Amory: You said that you self-diagnosed yourself as autistic. How did you do that?

David: OK. Well, I'm a high school teacher. Sometimes we get special education students and a special education student will come with an IEP, which is an individual education plan. I was given an IEP for a student who was autistic and I thought autistic, what's autistic? So I started reading the paperwork and then I got online to look for more information and as I read the traits commonly associated with being autistic, I began to think, oh, my God, that sounds like me. I waited about a year because I, I didn't know what to do. Eventually a year came and went finally, when I got my diagnosis, it was as though a tremendous weight was lifted off me. And I thought, aha. Now there's actually a neurological reason for why I am the way I am. So then I didn't feel bad about myself because I am the person I am.

Ben: How did that feel?

David: It was liberating, one of the first thing, I did several things. One was I realized now why I was being so stressed out. I was I had a large school. I mean, we had like over 3000 students And so I transferred to a small rural school within the same district. Um and then moving away, that was really good excuse to say, hey, I'm moving. It was nice knowing you bye, and saw I was able to end the few friendships I had. And that's also reduced a lot of stress. So I just found it very liberating. You know, I basically gave myself permission to be a reclusive introvert. When I'm not at work, I'm at home. And when I'm at home, I expect to be left alone. So my cell phone is off. I don’t answer the door. I have a welcome mat. Well, it’s not really a welcome mat. It says go away.

(Amory laughs)

David: You see, you're doing the same thing that that that my friends have done because…

Amory: They think it's a joke.

David: I’m actually being quite serious.

Amory: Yes.

David: I don't want you ringing up my my doorbell or knocking on my door. But people think it's a joke and it's not a joke, at least not a joke to me.

Ben: Do you have friends?

David: I have colleagues that I am cordial with, but no, I I would not say I have friends. I have people who tell me that they're my friends. But but I really limit my interaction with anyone when I'm off campus.

Ben: When was the last time you went out to dinner with with other people?

David: Oh, my. Three years ago maybe. I do go out to dinner, but I go out by myself and I take my my cell phone or take a Kindle tablet and I just read.

Ben: You have cats, right?

David: I do have cats.

Ben: Are you friends with your cats?

David: Yes. Yes, and to some some extent, they remind me, it's like they autistic also because they love set routines. And and they don't always listen. And sometimes communicating with them can be a challenge.

Amory: What are their names?

David: I have an alpha cat who's black and his name is Booky Boy and I have an alpha female named Chi Chi. And then there's a second there's another female called Huma. Chi Chi's brother is Hunter. And then I've got a big fat gray tabby named Scrappy Cat.

Ben: Sounds like a good crew.

David: Yes, I actually just bought a new house in April primarily to accommodate the cats.

Amory: Oh, nice. Congratulations.

David: Yes, thank you.

(music plays)

David: So you know Thanksgiving, I spent at home by myself with my cats. And so I got on Reddit. And I don't mind interacting that way.

Amory: So it's a way for you to have interaction when you don't necessarily want in-person company.

David: Yes. Yeah, so I can offer constructive advice that way because at one point I was thinking about forming an autism support group for this area. And then I realized, oh my gosh, people are going to be calling me for all sorts of things. And I didn't want that. It seemed too intrusive.

Amory: That’s fair. Are there things that you appreciate about being autistic?

David: Oh, yes, absolutely. I have a very narrow focus. I'm very project oriented. In fact, that's one useful thing about having cats, because the cats get a little peeved if they don't get fed and they will tell me. So I may forget to feed myself, but I never forget to feed my cats because they'll come and get me. I do realize having learned more about autism that a lot of us on the spectrum have the prevailing one or more prevailing interest. And it was just a happy coincidence that I was able to leverage this into a career, you know, teaching culinary arts.

Amory: It seems like being in front of a classroom full of students feels like the opposite of being at home by yourself with cats who also want to be by themselves.

David: Yeah, you're right. So there’s a term that is often used by people on the spectrum. It's called masking. Long ago, even before I learned I was autistic, in my mind, I was modeling a teacher. I was roleplaying being a teacher. When I was an elementary teacher, I was one of those people who would dress up in period costumes. So when I taught fourth grade the age of exploration, I would come to school dressed as a conquistador and I had handcrafted steel breastplate. I had three hundred dollar thigh-high custom-made a hand stitch leather boots on the baggy trousers and the puffy sleeve doublet. But it helps with reinforcing this persona.

(music plays)

Ben: Figuring out how to navigate your professional life — maybe by adopting a persona as David has — that’s one thing. Navigating the most wonderful, socializing-filled time of the year, is something else.

Amory: For David, it’s an opportunity to develop another persona, as a crooner.

Ben: We understand that you wrote a Christmas Carol.

David: I did! So it's three verses and it's to the tune of Deck the Halls. So this is it.

(singing)

Lock the doors and douse the lights. FA la la la la la la la la.

Christmas cheer fills me with fright. FA la la la la la la la la. Stay away you’re all annoying. FA la la la la la la la la la la. Merriment is horribly cloying. FA la la la la la la la la la la. Mistletoe makes me real nervous. FA la la la la la la la la. Kissing me would be a disservice. FA la la la la la la la la. 80 million germs abound. FA la la la la la la la la. Infecting me could put me in the ground. FA la la la la la la la la la. It's not that I hate you. I'm autistic. FA la la la la la la la la la. I need my space. Is that so, mystic? FA la la la la la la la la la. I'm happiest when left alone. FA la la la la la la la la. Socializing makes me groan. FA la la la la la la la la, fa la la la la la la la la la la la.

Amory: Yay (applause)! Thank you, David!

David: If I could just say one other thing. You know, I am reclusive. There are people on the spectrum who do want to socialize. There are people on the spectrum who are actually married or who date. You know, we're all quite different, which is why it's called the spectrum.