Advertisement

Did Moses Inspire the Underground Railroad and Superman's Creators?

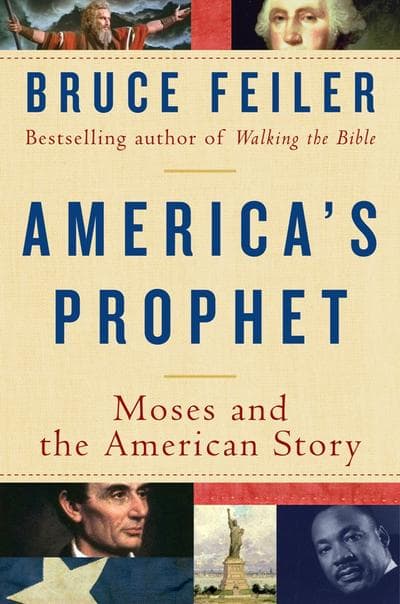

Jews believe Moses led them to the promised land, but according to best-selling author Bruce Feiler, he also inspired the Founding Fathers, the slaves on the underground railroad and the creators of Superman. Here & Now's Robin Young spoke with Feiler about his new book, "America's Prophet: Moses and the American Story". The following is an excerpt.

--Thanksgiving is the mandatory holiday in my family. It’s the one time of year when we clear our calendars, pack up gifts, and travel across the country for a ritual that is one part Americana, one part Hanukkah, one part nostalgia. The event begins when my mother polishes dozens of apples, pears, pomegranates, and kumquats and arranges them with a pumpkin, some Indian corn, and cranberries to create a cornucopian centerpiece. It continues with Thanksgiving dinner, a mix of trendy roasted this and that along with some embarrassing

1950s classics we love, notably a hot fruit compote made with five different kinds of canned fruit baked with macaroons and sherry. During the meal, in a custom that makes me cringe yet always seems to work, my sister insists that we go around the table and say why we are thankful. The weekend concludes with an early celebration of Hanukkah, the Jewish festival of lights. It’s a classic American event, a mix of church, state, shopping, and turkey.

Passover is the equivalent holiday for my in-laws. Every spring, my mother-in-law hosts thirty-five people on one night and a different thirty-five people the second night for a ritualized retelling of the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt. The food is equally ritualized: chicken soup with matzoh balls; gefilte fish with hot pink horseradish sauce; “Debbie’s tasty brisket” with carrots and potatoes; and Auntie Barbara’s Jell-O mold with, yup, canned fruit. Passover is so important to my in-laws that when they expanded their home some years ago they redid not their bedroom or bathroom but their dining room, just for these two nights a year. The centrality of these two holidays to our respective families is such that when my mother met my future mother-in-law for the first time they retreated into a corner and came out a few minutes later with smiles on their faces: The Feilers would get Thanksgiving; the Rottenbergs would get Passover.

Though it took me a while to realize it, discovering the unexpected bridge that links these two holidays would occupy the coming years of my life.

Before att ending my first Passover with my in-laws, I warned them that I would make the world’s most insufferable seder guest. I had just returned from a yearlong journey through the Middle East, in which I actually crossed the likely Red Sea, tasted manna, and climbed the supposed Mount Sinai. In the liturgical list of Four Sons included in the seder service, I would surely be the Pedantic One. In ensuing years, I continued my biblical wanderings, traveling through Israel, Iraq, and, with my bride, Iran. “A honeymoon in the Axis of Evil,” she called it. A year later she gave birth to identical twin girls: Eden, for the Garden of Eden; and Tybee, for the beach near Savannah where I grew up and where we celebrated our wedding. They seemed like emblems of our lives: ten toes in the Middle East, ten toes at home.

ending my first Passover with my in-laws, I warned them that I would make the world’s most insufferable seder guest. I had just returned from a yearlong journey through the Middle East, in which I actually crossed the likely Red Sea, tasted manna, and climbed the supposed Mount Sinai. In the liturgical list of Four Sons included in the seder service, I would surely be the Pedantic One. In ensuing years, I continued my biblical wanderings, traveling through Israel, Iraq, and, with my bride, Iran. “A honeymoon in the Axis of Evil,” she called it. A year later she gave birth to identical twin girls: Eden, for the Garden of Eden; and Tybee, for the beach near Savannah where I grew up and where we celebrated our wedding. They seemed like emblems of our lives: ten toes in the Middle East, ten toes at home.

One theme of these travels was exploring the explosive mix of religion and politics. But I realized upon returning that the front line of that battle had migrated back home. The United States was involved in its own internal war over God that in many ways mirrored—and in some cases fed—the wars being waged in the Middle East. The buzzwords only hintedat the battle lines: left/right, red/blue, believer/nonbeliever, extremist/moderate.

These tensions were reflected in all the usual places of modern discourse—the ballot box, the call-in show, the Bible study, the book group. Yet they were most acute at home. So many of the laments I heard about religion were variations on a theme: “I can’t talk to my brother about it without getting into a fight.” “My father is a Neanderthal.” “My daughter is making a big mistake.” “He doesn’t understand what made this country great.” With greater mobility and more choices, we no longer passed down religion seamlessly from one generation to the next. Nearly half of Americans change religious affiliations in their lives, a Pew study concluded. Stuck with our parents’ genes, we seemed less interested in being burdened with their God as well. And we certainly didn’t want to talk to them about it.

Thanksgiving, the symbol of American blessing, the one holiday that marked the union of God, the people, and the land, had, for many families, become a minefield of fraught conversation.

Around this time I began noticing something else. On a trip to visit my in-laws on Cape Cod, we stopped off in Plymouth and I took a tour of the Mayflower II. A reenactor was reading from the Bible. “Exodus fourteen,” he explained. “The Israelites are trapped in front of the Red Sea, and the Egyptians are about to catch them. The people complain, and Moses declares, ‘Hold your peace! The Lord shall fight for you.’ Our leader read us that passage during our crossing.” Moses, on board the Mayflower. On a trip to visit my parents in Savannah, I stopped off at my childhood synagogue. A letter from George Washington hangs in the lobby, sent after his election to the presidency: “May the same wonder-working Deity, who long since delivered the Hebrews from their Egyptian oppressors, planted them in the promised land, whose providential agency has lately been conspicuous in establishing these United States as an independent nation, still continue to water them with the dews of Heaven.” Exodus, on Washington’s pen in the first weeks of the presidency.

On a trip to visit my in-laws on Cape Cod, we stopped off in Plymouth and I took a tour of the Mayflower II. A reenactor was reading from the Bible. “Exodus fourteen,” he explained. “The Israelites are trapped in front of the Red Sea, and the Egyptians are about to catch them. The people complain, and Moses declares, ‘Hold your peace! The Lord shall fight for you.’ Our leader read us that passage during our crossing.” Moses, on board the Mayflower.

On a trip to visit my parents in Savannah, I stopped off at my childhood synagogue. A letter from George Washington hangs in the lobby, sent after his election to the presidency: “May the same wonder-working Deity, who long since delivered the Hebrews from their Egyptian oppressors, planted them in the promised land, whose providential agency has lately been conspicuous in establishing these United States as an independent nation, still continue to water them with the dews of Heaven.” Exodus, on Washington’s pen in the first weeks of the presidency.

On a trip to visit my sister in Philadelphia, we went to see the Liberty Bell. The quotation on its face is from Leviticus 25, which God gave to Moses on Mount Sinai: proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof. The law of Sinai, in the bell tower where the Declaration of Independence was signed.

In coming weeks, I found a similar story over and over again. Columbus comparing himself to Moses when he sailed in 1492. George Whitefield quoting Moses as he traveled the colonies in the 1730s forging the Great Awakening. Thomas Paine, in Common Sense, comparing King George to the pharaoh. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams, in the summer of 1776, proposing that Moses be on the seal of the United States. And the references didn’t stop. Harriet Tubman adopting Moses’ name on the Underground Railroad. Abraham Lincoln being eulogized as Moses’ incarnation. The Statue of Liberty being molded in Moses’ honor. Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and Lyndon Johnson tapping into Moses during wartime. Cecil B. DeMille recasting Moses as a hero for the Cold War. Martin Luther King, Jr., likening himself to Moses on the night before he was killed. The sheer ubiquity was staggering and, for me, had been completely unknown.

For four hundred years, one figure stands out as the surprising symbol of America. One person has inspired more Americans than any other. One man is America’s true founding father. His name is Moses.

For two years, I traveled to touchstones in American history and explored the role of the Bible, the Exodus, and Moses in inspiring generation after generation of Americans. I examined how American icons of different eras—from the slave girl Eliza carrying her son to freedom across the Ohio River in Uncle Tom’s Cabin to an orphaned Superman being drawn out of a spaceship from Krypton— were etched in the image of Moses. And I probed the ongoing role of Moses today, from the Ten Commandments in public places to the role of the United States as a beacon for immigrants. Even a cursory review of American history indicates that Moses has emboldened leaders of all stripes—patriot and loyalist, slave and master, Jew and Christian, fat cat and communist. Could the persistence of his story serve as a reminder of our shared national values? Could he serve as a unifying force in a disunifying time? If Moses could split the Red Sea, could he unsplit America?

This program aired on October 9, 2009. The audio for this program is not available.