Advertisement

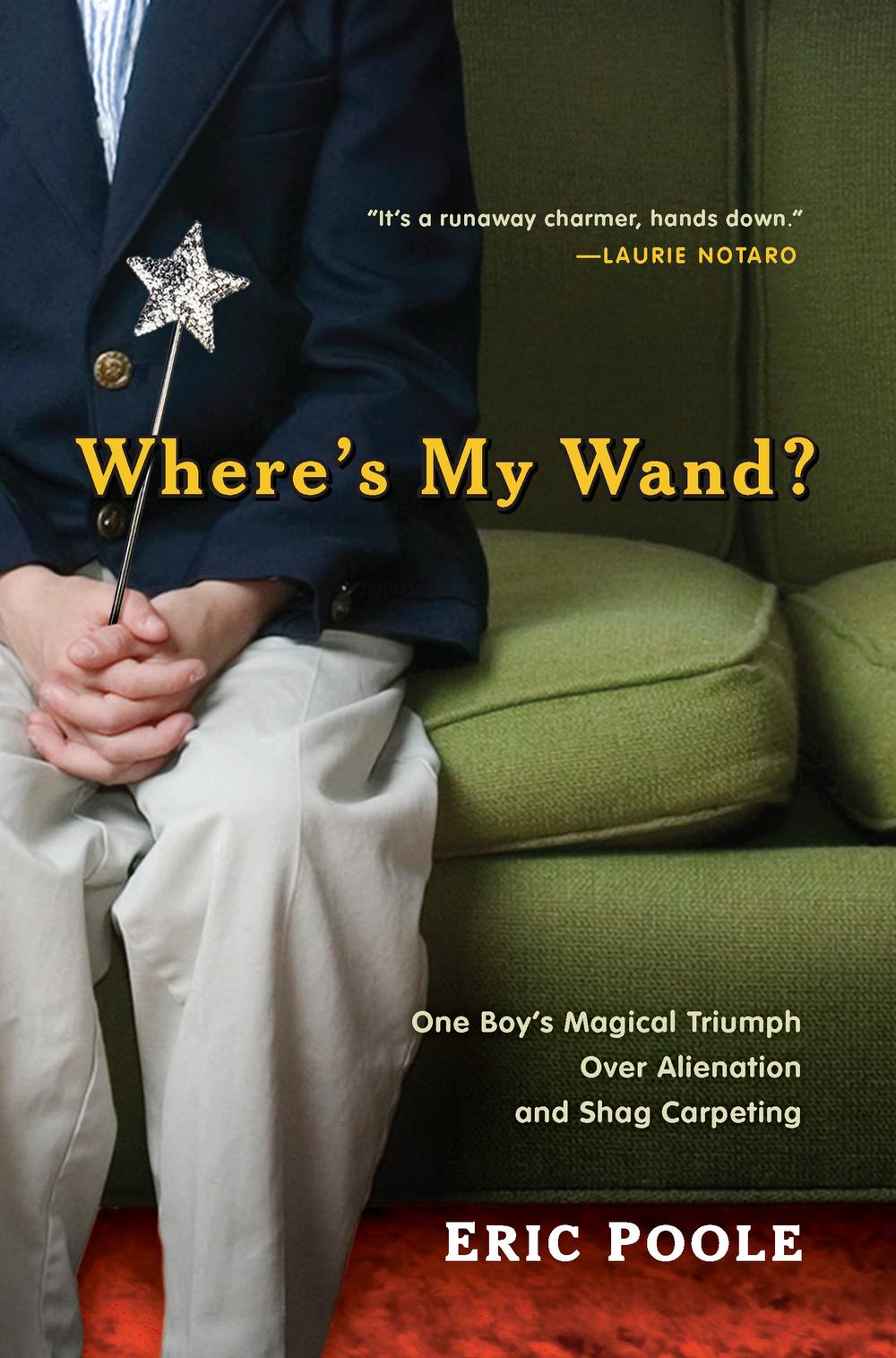

Book Excerpt: 'Where's My Wand?'

In this excerpt, from author Eric Poole's novel, “Where’s My Wand: One Boy’s Magical Triumph over Alienation and Shag Carpeting,” he struggles to deal with his mother's obsession with keeping the house clean, driving the rest of the family crazy in the process.

"As God is my witness,” Mother shouted, “I will not live in this chaos!”

"As God is my witness,” Mother shouted, “I will not live in this chaos!”It was a muggy St. Louis summer night in 1969. As our mother screamed at our father behind the closed door of their bedroom—“Did you even get halfway through this list?” she hollered, slamming the daily checklist of duties she made for him onto the dresser—Val and I focused on the faint electrical buzzing of the Black & Decker bug zapper hanging over the patio, as it systematically executed unsuspecting mosquitoes.

It was ten P.M. and no one was outside, but our mother kept the zapper running twenty-four hours a day as a silent screw-you to Mother Nature. To offset the cost of this outdoor insect patrol, she set the air-conditioning of our suburban tract home at a toasty eighty-four degrees, so we all slept in small pools of perspiration, secure in the knowledge that those bugs knew who was boss.

I clung to my twelve-year-old sister Valerie, both of us sweating profusely as she climbed into her canopy bed fringed in multicolored hippie beads. She squeezed my hand tightly.

“One day,” she whispered, “we’ll look back on this and laugh.”

“I will not be married to a sloth!” Mother thundered as I quietly reached for Val’s dictionary to look up what Dad had just been called.

The bedlam Mother referred to was that created by our father opting to play Kerplunk with Val and me that afternoon, instead of completing item #7, alphabetizing the Christmas decorations stored in the garage, or #13, washing the lightbulbs on the dining room chandelier.

The hippie beads shimmied as Val, my only sibling, settled between the sheets. She was a petite but bossy brunette who spent hours each day ironing her long hair Marcia Brady– straight—in an effort, she told me years later, to distract from the nose that made her appear to be the love child of Karl Malden and Barbra Streisand. As she attempted a smile and turned to switch off the lamp that I had just traded her for the Diana Ross and the Supremes Greatest Hits album (thus unwittingly sealing my sexual identity at the tender age of eight), I began to ritualistically rake the shag carpeting around the bed with an avocado-green plastic carpet rake, vigilantly erasing all signs that anyone had trod upon her floor. The carpet slowly became a pristine meadow of brown, white and gold, a lush, undisturbed wool and nylon Astroturf.

With the well-rehearsed precision of hundreds of nights’ practice, I worked my way down the hall, slowly approaching the closet where the rake would be stored upon completion. Fortunately, the closet door—along with all other doors in the house—could be closed without disturbing the integrity of the finished job. Following an apocalyptic moment after the carpet was installed—when our mother discovered that entering a room created the shag version of snow angels— Dad had planed each of the doors, sawing off a full inch of wood at the base, rendering them so high-water that each doorway now appeared to be wearing wooden capri pants.

As I passed the bathroom, Val stuck her head out of her bedroom. “Don’t forget to pee!” she whispered, reminding me that I would need to go now or hold it until morning, since Mother tolerated no disruptions in the placid waters of this sea of shag once the requisite raking was finished. I had learned not to consume large amounts of liquid before bedtime, ever since the night I had drunk an entire quart of Coke and, in desperation, had tried to pee out the bedroom window screen.

My pursuit of a flawlessly raked floor did not strike me as odd, since perfection was not optional in the Poole family militia; it was compulsory. It was also the means by which I attempted to maintain control over the rapidly shifting ground beneath my feet.

Our family had just moved from Iowa to Missouri for a new and better life. Dad had accepted a job in contract administration with a major aircraft company, and Mother was to become the executive assistant to a corporate chieftain, and together, their new careers were to be the start of a prestigious change of life for the Pooles.

What transpired instead was a series of matinee and evening performances of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? sans the Edward Albee script and intermissions, as our parents’ relationship seemed to be disintegrating before our eyes, and my sister and I attempted to determine which of us was responsible.

As I worked my way down the hall with the carpet rake, closing in on my parents’ bedroom, the level of Mother’s voice rose. “How I married someone so completely devoid of competence,” she barked, “is an absolute mystery. I had my pick of any man in Kansas City—”

Outside the door, I carefully coaxed each carpet strand into absolute alignment. There would be no defectors in my Carpet Crusade, no errant soldiers in this battle for perfection.

“The kids can hear you,” Dad whispered. “You need to stop this right now.”

“Or what?” she hissed. “Don’t you dare threaten me.” “I’m not threatening anybody, I’m just saying—” “You make me sick, you know that?”

The bedroom door flew open. Dad—a slender, six-foot-tall man with a prominent nose and a glossy shock of wavy black hair—grabbed his car keys from the dresser and stomped down the hall.

“Don’t leave!” I cried, before even realizing the words had escaped my mouth. I grabbed my father’s leg, my hands clutching his ankle.

Mother appeared in the hall wearing a floral print duster and a thick layer of cold cream on her face. She was a petite woman with a stunning figure and a graceful, angular beauty that was, perhaps unsurprisingly, lost on me in this moment.

“Fine. Get out!” she bellowed, as my fingers dug deep into the thin fl esh above my father’s foot. He moved slowly toward the door, attempting to gently dislodge me as I hung on for dear life beneath a hanging glass swag lamp.

Val had quietly slipped into the family room. She ran to our father. “Take me! You can leave Eric with her,” she cried, throwing me to the wolves. “Just take me!”

“Go to your rooms,” Mother ordered us. “Both of you!” Neither of us moved, afraid that the consequences of leaving this room would be even worse than disobeying her.

Dad gazed longingly at his offspring for a brief moment, then pushed our hands away and opened the door. Without another word, he was gone.

There was a stunned moment of silence. I lay on the floor, my hands frozen in outstretched plea. Val and I turned to look at our mother, a mix of fear and contempt on our faces, as tears formed in her eyes. She twisted on her heel and swept into the bedroom, slamming the door with such force that the frame threatened to explode.

I stared at my sister, horrifi ed. After a long moment, she moved to pat my back as I began to cry in quick, gulping sobs, unable to catch my breath.

“Well,” she declared matter-of-factly, “you’re gonna have to rake all over again.”

PERHAPS IT WAS events like this that sparked my interest in magic.

Perhaps it was because my new third-grade teacher, a sadist in stilettos named Mrs. Locke, had it in for me. Today, Mrs. Locke would be able to positively channel her aggression into a career as a bounty hunter or an Attica prison guard, but in 1969, her only outlet was a group of unsuspecting third-graders, and one in particular.

Or perhaps it was because I had been given a gift-withpurchase upon arriving at my new elementary school, a sneering bully named Tim who, in concert with Mrs. Locke, conspired to infl ict as much emotional damage as was possible at the age of eight, obviously assuming there were prizes involved.

Whatever the cause, I worshipped the TV show Bewitched—and, to Mother’s irritation, could be found flattening the shag in the family room every Thursday night when it aired. The lovely wife, Samantha, her devoted husband, Darrin, and their spotless suburban home all mirrored my own family’s existence, but with a refreshing lack of screaming and crying.

Yet even more alluring was the magic. The notion of being able to snap my fi ngers, wave my hands or twinkle my nose and magically alter the circumstances of life was intoxicating, akin to learning voodoo or having Jesus owe you one. And the more I watched, the more I became convinced that somewhere within my own being, I must possess similar magical powers.

But whom to model myself after? True, Sam was young and beautiful and smart, but her mother, Endora—there was someone with style. Someone with a fl air for the dramatic.

Endora favored caftans, so my search began for an outfi t that would allow me to approximate her look. Long, flowing sleeves were especially important, for that theatrical, Endorastyle arm flourish as I performed episodes of life-changing magic.

While rifl ing through a basement closet one day, I stumbled upon an old white chenille bedspread. It was a little threadbare, but at double-bed size, it gave me plenty to work with. The Endora of St. Louis was born.

My becoming Endora was not something I felt my sister Val would embrace. As a rule, she tended not to favor her eight-year-old brother in drag. On the day of my transformation, I waited patiently for Val to leave for her best friend Vicki’s house, knowing that she would need to confi de in her about our dad’s sudden departure the night before.

Vicki McDougal lived up the street, and was quite sexy in a white-trash, I’m-only-twelve-but-I-wear-tube-tops way. I was unclear as to how Val and Vicki passed the time they spent together, but apparently it had something to do with auditioning makeup, since Vicki had a fishing tackle box fi lled with glitter foundation and blue eye shadow, and Val regularly came home looking like a clown trainee.

Our mother despised the McDougals. “They may not live in a trailer now,” she declared, “but those people are one step away from a steering wheel in the living room.”

“I’m going to Vicki’s,” Val announced, adding, “Don’t tell Mom, or you’ll be the next one thrown out.” She slammed the door behind her. I rushed to the window to perform a visual check. Val was halfway up the block, waving a Tiger Beat magazine and a bottle of Love’s Fresh Lemon perfume at Vicki.

I flew downstairs to the basement, where I had hidden the chenille bedspread behind a mohair recliner. The chair was positioned against the wall, so my parents were unlikely to look behind it, since Mother—despite being a highly motivated neat freak—only lemon-oiled the paneling every few weeks. I pulled out the bedspread, picked off the Acrylon lint from the orange industrial carpeting, and began to carefully drape it over my body, adjusting the sleeves to ensure that they did not flow past my wrists, so as not to interfere with the magic I was sure would be emanating from my hands.

First, I conjured up the image of my new schoolteacher, Mrs. Locke. She was a tall, rail-thin woman with high heels and a twelve-inch blond beehive, and she towered over our class in a way that seemed not only menacing but outright dangerous, since her balance frequently appeared to be in peril.

She would lean over her desk, her pinched facial expression giving her the appearance of someone who was constantly sniffi ng a turd, and snap her fi ngers. “You! What’s your name?” I would scan the room, my head rotating like a police siren, desperately hoping that it was someone else’s turn. “Yes, you, you idiot, I’m looking right at you.” Then, even louder: “DID YOU HEAR ME?”

“My name is Eric,” I would reply, smiling angelically in a futile attempt at charm.

She would cross the room to tower before me, Godzilla looming over Tokyo. “Stop rushing through your tests that way, you’re not that smart.” Mrs. Locke was referring to my penchant for being the fi rst in the class to fi nish any exam or quiz. By now well aware that I possessed few selling points that those around me seemed to appreciate, I had tried using my intelligence as a method of currying favor, since I usually scored A’s. This worked like gangbusters on my art and music teachers, but Mrs. Locke was not the pushover that those creative types were.

“You think you’re Albert Einstein,” she continued, her voice booming over my head as I looked down, attempting to perform quantum physics by combining my atoms with those of the laminated beige desktop. “Well, we all know what happened to him.” Several kids tittered knowingly. Actually, none of us did know, but her ominous tone implied that hurrying through tests would result in some sort of particularly embarrassing or violent demise, like vomiting to death.

Back in the basement, I visualized that moment, contemplating as much of the humiliation as I could bear. Then, with a dramatic wave of my bedspread-laden arms, I disappeared— sailing through the cosmos at lightning speed, passing Venus and Jupiter, waving at angels and demons as I traversed the space/time continuum to return to the beginning of the school year.

I reappeared—now finding myself in a different classroom, with an adoring teacher named Maryann (she insisted that I call her by her fi rst name). She was petite, dark-haired, and had a warm, easy smile. Maryann announced to the students, “Children, I know that I shouldn’t have favorites, but . . .” She gazed fondly at me, her eyes misting up. “Eric is just . . . too . . . special.”

Maryann kept me after the last bell to give me hugs and show me the test scores of my classmates. We gossiped about the stupid kids, laughing and drinking Yoo-hoo in the forbidden inner sanctum of the teachers’ lounge. As Maryann and I walked arm in arm past Mrs. Locke’s classroom, chuckling over a private joke, Mrs. Locke, straining to hear, fell off her high heels. She landed on the cold, worn beige tile floor with a loud thud, denting her beehive, giving it the look of a honeycomb frequented by drunken bees.

It was a vastly fulfi lling moment.

I thanked Maryann for a wonderful day and bid her farewell, as she handed me a Pixy Stix for the road and wiped a tear from her cheek. Up into the sky I flew, breezing through solar systems as the cosmic dust of passing planets sparkled like glitter.

Suddenly, I began to veer off course, wrenched across the Milky Way by a force not of my own power. Was it a gravitational pull, a black hole, some unnamed, gaping void? I was silently and swiftly sucked into the desolate world of my current schoolyard, where I found myself standing face-to-face with my unbearably attractive bully.

Tim was an athletic, stupid and shockingly handsome boy who was destined to become either a football hero or Prom Queen at the state penitentiary. Although not known for his extraordinary powers of deduction, Tim had discovered the deep, dark secret that I told few people: I was deaf in one ear.

As the new kid in school, with few check marks in the looks and athletic columns, I had concluded that physical impairments would probably not add to my luster. Unfortunately, because I inadvertently ignored Tim whenever he whispered something in my right ear, it became somewhat diffi cult to camoufl age, and between my I’m sorry, what?s and Mrs. Locke’s repeated DID YOU HEAR ME?s, he eventually concluded that I was, in his insightful words, a “one-ear.”

Partially hearing the taunts of a bully is diffi cult enough, but having to ask him to repeat them pretty much assures an impressive level of trauma. I momentarily fl ashed back to the previous day, when Tim—who had limited imagination and tended to double up on his material—had whispered, “You can’t run, you can’t play dodgeball, and you can’t hear— you’re a triple threat!”

Naturally, all I felt was a rush of air against my neck, so when I turned and, in my most nonthreatening, please-don’tbeat-me-up voice, replied, “What did you say?” he repeated it at a volume that would wake Helen Keller. Everyone within two earshots guffawed.

I executed a theatrical Endora-inspired wave, my caftaned sleeves billowing through the air. Tim and I disappeared, swallowed into the earth, screaming through dirt and rock and molten iron, atoms and energy colliding into alternate dimensions. Within seconds or minutes or maybe lifetimes, we reappeared on the playground of our school.

Tim was standing before me. But something was different. He was much more subdued. He slumped a little when he walked. His confi dence was shaken. Tim was deaf.

Exhilaration washed over me as I contemplated my sudden advantage. The sheer number and variety of taunts now available was overwhelming: “Hey, no-ears!” or, while fl ipping him off, “I speak sign language!” or my personal favorite, “You’re Beethoven without the talent!” Even though this last one would doubtless go over most of their heads, kids from all corners of the playground would howl with laughter, pointing and sniggering, the raucous jeers slowly building to a, pardon the pun, deafening roar.

But ultimately, I chose silence. Perhaps I was more desperate for friendship than revenge. I picked up a large rubber

ball, then backed up across the basement playground. As I prepared to throw it at him, he adopted the offi cial Dodge-ball Stance, ready to scamper left or right, and grinned. We began to play.

As the afternoon began to wane, I waved good-bye to Tim and promised to return for a tiebreaker. I waved my arms and began to drift down through the clouds and into the family room of our home, where—in the final moment of my magical conjuring—I now saw Val and me enjoying a wicked game of Chutes and Ladders.

We heard a car pulling into the garage.

“Dad’s back!” Val shrieked happily. We threw the door open and ran to greet him at the car. We were not in any way a physically demonstrative family, but in this tender, imaginary moment, as we leaped into his arms, he hugged us tightly, stroking the backs of our heads as he whispered, “Never again. Never again.”

Suddenly, I was jolted out of my magical vision by the sight of my sister standing in the basement, reeking of lemon perfume, her eyelids an explosion of electric blue powder.

“Why are you wearing a bedspread?” She eyed me disdainfully.

“How did you get in?” I fumbled defensively. “You left your key here!”

“Vicki has one,” Val replied. She surveyed my costume. “So what’s with the white cape, Superwoman?”

I yanked the bedspread off, embarrassed. “It’s not a cape, it’s a . . . okay, it’s a cape,” I mumbled, realizing this was

probably the lesser of two wrong answers. I stood up straight. “I am BibleBoy, Defender of Righteousness.”

“Oh, brother,” Val replied, rolling her eyes. “You are so eight.” She thrust her wrist under my nose. “How do I smell?”

That evening, as Val and I performed our dinner ritual of heating Mother’s premade frozen casserole, I thought about this near miss, and what would happen if I were ever truly discovered. I would probably be sent to Windermere, the local Christian summer camp, which was Vacation Bible School but with bunk beds and torture (the camp was widely known to be populated by Missouri’s top Christian bullies). I vowed to be more careful, lest I end up another casualty of the love of Jesus.

The garage door opener began humming. Mother was home.

Val and I prepared for the theatrics that often accompanied Mother’s nightly return. Our afternoon attempts to render the house unlived in, free of all traces of human habitation, usually failed on a scale that could not be measured by existing devices, as her screams of frustration—“GOD IN HEAVENNNN!!”—pierced the evening sky. “WHY, GOD, WHY IS THERE WATER IN THIS SINK?”

The door opened. Mother stepped into the house, her head bent, a hollow, defeated expression glazing her delicate features. She dropped her purse on the kitchen table, smiled wanly at Val and me, and disappeared into her bedroom.

Silence. Val and I set the table, unable to look at each other. The satisfaction in seeing our mother cowed was overwhelmed by her palpable pain. This was unfamiliar emotional terrain.

Mother reemerged in her “comfy,” an ugly print housedress that had been washed several thousand times. We sat down to dinner.

“How was your day?” she quietly asked my sister.

Val, understandably uncomfortable with our mother’s sudden vulnerability, threw me under the bus. “I caught Eric wearing a bedspread,” she announced.

“It was a cape!” I hollered defensively. “I’m a superhero.” Mother turned to me. She smiled somberly and patted my hand.

“You can be anything you want to be.”

“He thinks he’s BibleBoy or some retarded thing,” Val declared.

“That is not retarded, young lady,” Mother announced sternly. We felt the storm clouds gathering, and began to anticipate an outburst, a fl ash of anger, a roiling moment of ire that, although diffi cult, would be familiar.

She turned to me with a fragile smile. “That is something to be proud of,” she said softly. “Are you saving the world one soul at a time?”

Before I could answer, the sound of the garage door opening galvanized the room. We turned to our mother as if for direction, unsure what her reaction would be.

Suddenly infused with energy, she jumped up and grabbed a plate and silverware from the cabinets, quickly setting a place for our father. She began to talk quickly, animatedly, making little sense. It didn’t matter.

The door opened. We heard our father’s footsteps across the family room. He entered the kitchen and took his place at the table, still wearing the same white undershirt, Dacron slacks and moccasins he had left the house in the night before.

“That casserole smells delicious,” he declared to Val and me, not looking at our mother. “You can’t go wrong with mushroom soup and Funyuns.”

“Do Funyuns grow in the ground or on trees?” I asked Dad in a rush of words as he sat down.

“In the ground,” he replied, smiling at Val and me without meeting Mother’s gaze. “Maybe we’ll plant some in the garden,” he continued. “It takes a real green thumb to grow ’em with that crispy coating.”

Throughout the meal, Mother and Dad never once locked eyes; but it didn’t seem to matter. Somehow, a truce was negotiated. Armistice was established. And dinner progressed into a tranquil evening unmarred by outbursts.

And I began to believe that perhaps, with the help of a basement and a bedspread, magic could happen.

Copyright © 2010 by Eric Poole