Advertisement

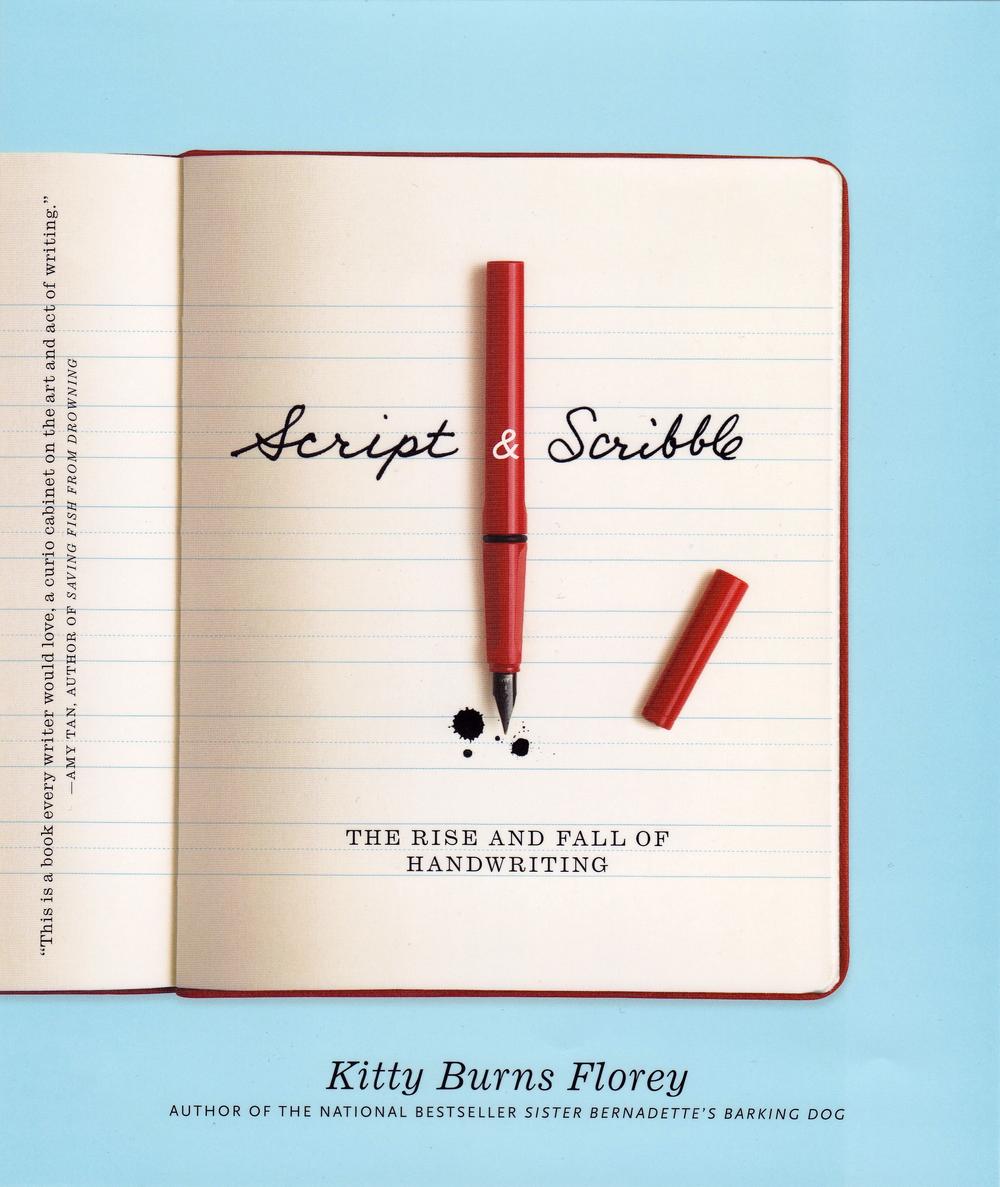

Book Excerpt: Script & Scribble

“Try to go a day without writing anything by hand — you can’t.”

“Try to go a day without writing anything by hand — you can’t.”Author Kitty Burns Florey reminded us that when we spoke with her last year about her book, “Script & Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwriting.” The book is a history of handwriting, from ancient times to modern America, and a passionate argument for teaching and learning good penmanship.

Florey told us about research showing that the physical act of learning to write helps children learn to think, and pointed out that without good penmanship of our own, we can’t read what other people write. Read an excerpt of "Script & Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwriting" below.

_________________________________________

Preface: A Handwritten Life

Since I first picked up a pen, I have been under the spell of handwriting. I've experimented endlessly with different scripts: straight up, right-slanting, left-slanting, print-like, florid, spare, minimalist, maximalist, round, spiky, highly legible, insouciantly scrawled. I can't make a list or write a check without scrutinizing my rushed, ugly f's and illegible r's and wishing I'd taken more time or had a better artistic sense. When I doodle, I often doodle handwriting styles.

I suspect that, for many, this preoccupation might seem bizarre, even slightly mad. There's a widespread belief that, in a digital world, forming letters on paper with a pen is pointless and obsolete, and that anyone who thinks otherwise is right up there with folks who still have fallout shelters in their back yards. But I'm part of the last generation for whom handwriting was taught as a vital skill. All through school, it was an important part of our lives: you had good handwriting, or you had bad handwriting – at some level, the way you wrote was a part of you, and was judged. That identification with my own script has never left me.

When I look back at learning to write, I can still feel the excitement of it. Little kids printed. Big kids wrote in longhand.

I learned to write longhand—cursive—in third grade at St. John the Baptist Academy in Syracuse, New York. Above the blackboard there was a frieze showing the idealized script we were all aiming at, in both upper and lower case, and lurking in each student's beat-up old wooden desk was a Palmer Method workbook.

Every day, during handwriting practice, we took out our workbooks, sat up straight at our desks, and grabbed our pencils. Sister Victorine swished around the room in her long black habit, looking over our shoulders with her eagle eye and beating time like an orchestra conductor—one two, one two, up down, up down—a brisk martial rhythm that we labored to match with the strokes of our pencils.

Form, size, slant, spacing: those were the elements of the Palmer Method. At the end of the session, if you managed to keep them all in mind while you sat straight but also stayed relaxed, and if you concentrated on what you were doing instead of wishing you were out in the school yard playing Red Rover, you had pages of perfect ovals, upstrokes, and downstrokes, and by the end of third grade, these would have come together into some species of legible penmanship.

By the time we left Sister Victorine and entered Sister Robert Clare's fourth-grade class, we were deemed to be accomplished hand-writers and were allowed to progress from pencils to straight pens, which cost a nickel each. They were fitted with metal points (nibs) that we dipped into small glass inkwells fitted into a hole at the upper right (too bad, lefties!) corner of our desks. Writing with a straight pen dunked into an inkwell was an adventure: the path from ink to paper could be a sea of blots and blobs, and keeping the ink-flow steady on the paper was maddeningly difficult.

By fifth grade, we had graduated to fountain pens and were writing with some fluency—well enough, at least, to stop worrying about getting it right and start thinking about what impression we were making. This was the age when pen obsessives were born. In the diary I kept when I was ten, one of my New Year's resolutions was: "I will write ROUND"—ROUND was a fad among my set—and so I did.

But it wasn't until high school that the nuns finally allowed us, grudgingly, to write with ball-points. In my school, at least, there was a nunly prejudice against them as newfangled nonsense. The ball-points of the day were regarded as not only unreliable and messy (they did tend to skip and smear) but extravagant: when the ink ran out, you threw away the innards and bought a refill! It was almost as bad as buying a new pen every time! But among us devil-may-care adolescents, who worried about such trivial concerns? I was very fond of my blue Esterbrook fountain pen, my collaborator in hours of scriptomaniacal experiments. But everyone knew that ball-point pens were way cool, and eventually the nuns stopped fighting them.

Then felt tips came along. I remember when the first benzene-scented Magic Markers hit my high school, first in basic black, soon in glorious Technicolor. If you handed me one now, its intoxicating chemical stink would, in a Proustian second, transport me back to a winter afternoon at St. John's when, wearing a hideous maroon serge uniform, knee socks, and saddle shoes, I sat with a group of fellow students and, with colorfully marker-stained hands, made signs for pep rallies: BEAT ASSUMPTION! CRUSH SACRED HEART!—sentiments comprehensible, perhaps, only to basketball-crazed parochial school students without a shred of irony.

I used to change my handwriting the way I changed my hair color (my natural mousy brown ran the gamut from a sort of palomino to a daring reddish-black). It's obvious now that most of my scriptorial attempts were outrageously pretentious, appallingly twee, but I considered each one the height of cool—the proper handwriting for an aspiring Bohemian, a future writer, a deeply sensitive person who wrote deeply sensitive poetry and then burned it in the sink, weeping. Just as nineteenth-century ink nuts—a common species in those days—believed that good penmanship would lead directly to good moral character, I think I must have believed that an arty style would make me an artist.

What I was really looking for, of course, was my self. The notion that it would arrive through a bottle of Miss Clairol or the way I made a capital B was not, I hope, entirely inappropriate for my age group.

© Kitty Burns Florey; reprinted courtesy of Melville House. All rights reserved.

This program aired on October 7, 2010. The audio for this program is not available.