Advertisement

Diana Kennedy Brings Mexican Cuisine To The World

Editor's note: This segment was rebroadcast on July 29, 2022, in memory of Diana Kennedy. Find that audio here.

Cookbook author Diana Kennedy has been called the Julia Child of Mexican cooking. She's been traveling the country's back roads for more than 50 years with her pickup truck and a bedroll. What she's brought back from those journeys is the staggering variety and sophistication of Mexican folk cooking: unique varieties of chilies and corn and original recipes for everything from chocolate to ants and fungus. She also brings us ingredients, techniques and food customs overlooked even in Mexico as the country changes.

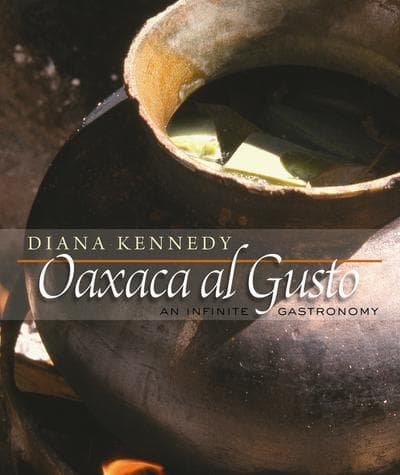

We speak with Kennedy about her life, work and her newest book, "Oaxaca Al Gusto: An Infinite Gastronomy."

Oaxaca al Gusto: An Infinite Gastronomy

By Diana Kennedy

The Pillars of Oaxacan Cuisine

Chocolate

By Fray Eugenio Martín Torres Torres

In Oaxaca, chocolate is more than history. It signifies the binding of a pueblo to its roots and to the belief that the divine (sacred) purifies, gives new force to, and celebrates life.

Before their evangelization in the sixteenth century, the Zapotecs conceived a life force called pee, which translated into Spanish means "wind, breath, spirit." Pee created life and movement for man and the things surrounding him. The Zapotecs believe this force shook the earth during an earthquake, created lightning in the heavens, moved the clouds, caused the beating of the heart, and formed the foam on the chocolate served in a

gourd.

Perhaps this explains why, during the pre-Hispanic period, chocolate was a drink reserved for nobles, who themselves only drank it on very special occasions. In contrast,

the macehuales, or plebians, were not allowed to drink it. Their drinks were atole and water, and they were only allowed to drink chocolate when the nobles ordered them to do so on particular feast days.

After the Spanish Conquest, chocolate ceased to be a drink exclusive to the nobles, but it commanded a very high price. Nevertheless, over time, it became so popular that even the ancients saw in it one of the causes of an epidemic that decimated the population. It was said that chocolate made "pesadas las carnes" (the meat/flesh gross), took away the

appetite and all desire to work, and caused the onset of incurable diseases.

The indigenous products most demanded by the Spaniards were gold, silver, cochineal, and cacao. The Spaniards readily embraced the use of the latter, accepting it as money, tribute, medicine, or food, perhaps because of their predilection for sweetmeats and drinks.

Advertisement

The principal markets for the commerce of cacao were in the City of Oaxaca and the town of Tehuantepec. In the former, it was sold or bartered in the large Saturday market, while in Tehuantepec, it was sold not only in the weekly market but bytehuanas traveling throughout the surrounding area.

Early in the evangelization of Oaxaca the Dominican friars desacralized the collection of cacao pods and accepted them as a source of energy and a remedy for kidney troubles,

pleurisy, stomach problems, sores, and sunstroke. By the middle of the sixteenth century, the drinking of chocolate was habitual among the clergy, but there were those who criticized this practice because they believed it should be used solely as a remedy. Among the latter was Fray Jordán de Santa Catarina, a missionary in the Sierra Norte, who was against this abuse of chocolate, maintaining that the devil had perverted this "medicine" by the sinful addition of sugar and by drinking it at all hours of the day. Other Dominicans defended chocolate, saying that it provided a source of energy and a consolation to the heart.

There was no lack of chocolate in the fiestas of Santo Domingo, Santa Rosa, and Santo Tomás de Aquino, during which the frailes accompanied it with torteras de pasta, soletas (ladyfingers), bizcochos (a type of yeast bread), pastelones (cakes), and flowers and figures made of pastry.

In life outside the convents, chocolate was not generally used until the early seventeenth century, when this slightly bitter drink of chocolate dissolved in hot water or milk and sweetened with raw sugar, vanilla, or cinnamon spread across the world. This hot chocolate, more suited to Spanish palates, was of course an adaptation of the indigenous Oaxacan pre-Hispanic drink that was drunk cold. The cacao was mixed with ground maize, or masa, diluted with water, and often sweetened with honey. It was also frequently flavored with chile, herbs, or seeds like those of achiote, which added different tones of purple, orange, black, and even white.

In the first decades of the seventeenth century, while hot chocolate was spread and praised throughout the world, the indigenous people of Oaxaca continued to prepare it in their unique ways. For instance, in the second half of the sixteenth century, in Atlatlauca and Malinaltepec, the cacao beans were ground with a maize dough, or masa, and drunk from tecomates (a type of gourd), whereas in La Chinantla, the ground pit of the mamey fruit (Pouteria sapota) was added to the masa.

Even today, in many indigenous communities of Oaxaca, drinking chocolate signifies the honoring of life, being at one with family, neighbors, the community, and, above all, with God, the patron saints of the church, and the dead. That is why, perhaps without being aware of this, Oaxacans always serve chocolate, prepared with water, at their celebrations, wakes, and novenas. The presence or absence of foam on the chocolate is important and signifies the type of occasion at which it is being served. For fiestas and reunions of the community, the thick and delicious foam on the chocolate atole signifies

happiness, brotherhood, and hope. At wakes, sorrow is momentary, for in Oaxaca there is no life without a fiesta, and there is no fiesta without chocolate.

Corn

By Amado Ramírez Leyva

Man selected teozintle (the wild forerunner of maize); he domesticated it and sowed corn. The corn, in turn, chose man and cultivated him, teaching him about the patterns and harmony of nature. It established itself in his kitchen and in his culinary

rituals.

Oaxaca plays a most important part in the history of corn, not only because it originated there but because it has spread from there in different forms to other areas of Mexico. Early macro remains (i.e., cob fragments) were found in the Guilá Naquitz cave near Mitla in the Valley of Oaxaca and date to about 4300 BC. No doubt corn will continue to spread because new varieties are constantly evolving.

In the kitchen--the intimate space dedicated to the creation and re-creation of dishes--we acknowledge each type of corn as a being with a separate identity, like every element in

nature: human, vegetable, or animal.

Corn is the foundation of the Oaxacan kitchen, used in the preparation of tortillas, tostadas, tlayudas, and totopos that, despite their lowly status, accompany nearly every dish. Corn transformed into masa is indispensable not only for atoles and other traditional drinks but also as the mainstay for many antojitos, for tamales, and for chochoyotes that are added to soups, moles, and other main dishes. Different types of corn can be transformed in different ways, depending on the creativity of the cook, but they can only reach their height of perfection when prepared in their traditional ways: "maíces bolita" from the Central Valleys for tlayudas and tejates, "maíces zapalote" from the Isthmus for

totopos, and "chalqueño" from the Mixteca for pozoles and tortillas.

This book attempts to bring some of the knowledge and lore from past generations that has been safeguarded in their land and kitchen hearths; there are many varieties of indigenous corn and edible plants ready to be accepted and appreciated in their diversity.

The Chiles of Oaxaca

By Diana Kennedy

Oaxaca is famous for its multicolored moles but not so much for the array of chiles that lend their colors and tastes to those moles. A stand selling dried chiles in the market is an

intriguing sight, and although they sell quantities of the better-known ones from other parts of Mexico, the chiles from around the state of Oaxaca stand out from the rest, identifiable by their unique colors and shapes: red and yellow costeños, from the coast, as their name implies, perhaps more difficult to distinguish from the red and yellow onzas from the Sierra Norte; the black, red, and yellow chilhuacles; and red chilcosles from

La Cañada, to name but a few.

The unique pasilla de Oaxaca or chile Mixe can still be bought according to size: small for sauces, medium for pickling in vinegar, and the largest for stuffing, each with its price

per hundred. Until very recent years, the Mixes themselves would be selling these chiles on strategic corners of the market, with their wares stowed in sacks made of henequen--now, alas, of plastic. These chiles are a deep reddish brown with a wrinkled skin. They are very picante and have a delicious fruity-smokey flavor from the process of smoke-drying the mature chiles — though, curiously, in their green state they do not have a

pronounced flavor.

The chilhuacles from La Cañada, both colorful and flavorful either fresh or dried, are indispensable for the moles of Oaxaca. They are generally shaped like a squat triangle, with exceptions of course. A ripe field of these chiles is a spectacular sight, for instead of ripening from green through yellow to red (like many other--but not all--types of chiles),

the fruits will start as a dark green, and each plant will ripen to either yellow, red, or a deep chocolate color. In this fresh state, they are used for local dishes, the most important of which is the very colorful chilecaldo given in the book. When dried, they are hollow with a thinnish skin and matte surface.

While they are light in weight--you get a lot for one kilo — because of limited production, they command a very high price compared with more prosaic dried chiles. In the same chilares (cultivated chile fields), there are also much narrower red chiles sometimes referred to as either chiles cuicatecos or chilcosles (the latter name is also sometimes given to the chilhuacle rojo, which is very confusing). There are also small bushes of what seem like miniature chilhuacles, which, when dried, turn a burnished orange color. These achilitos are used in uncooked sauces, notably that made from the seeds of the cardón cactus.

Another smallish chile, about 2 inches (5 cm) long, used for table sauces (as opposed to cooked sauces) in the valleys and part of the Sierra Sur is the taviche. While it is mostly

used dried, like many other chiles, it is only used fresh when in season, either after the rains or at other times of year where the fields are irrigated.

The chile tusta is a small, squat, triangular chile cultivated along the Pacific coast of Oaxaca and the foothills of the Sierra Sur. When fresh, it is a light yellow with patches of mauve, but its colors change to orangey red as it ripens. This chile is mostly used, when fresh, for table sauces, although it is also dried in small quantities.

Chiles costeños, both red and yellow, are grown extensively around the Pinotepa area. When fresh and still green, they are sold in the markets for sauces, but most of the crop is dried in the sun around the patios of the local houses to be used not only in table sauces but also in the local moles, broths, and stews as well as the local chilecaldo. There is a slightly larger, less picante variety that is added to the local black mole to lessen the

concentrated heat of the smaller variety. Chiles costeños are used extensively in local dishes such as sauces, chilates, and soups of the Mixteca area; in fact, they are grown, but on a smaller scale, in the Mixteca Baja and, I am told, in the neighboring coastal areas of the states of Guerrero and Michoacán.

The preeminent fresh chile used in the Central Valleys is the chile de agua. A typical one is about 4 inches (10 cm) long and about 1 inch (2.5 cm) across the top. The color varies from medium to light green, which changes as it ripens to an orangey red; however, it is mostly used while still green. Charred and peeled, it is either stuffed, covered with beaten egg and fried, cut into strips and macerated in lime juice as a relish, blended in a cooked sauce, or ground with other ingredients for a table sauce. I am told that until recently, it

was also used dried for sauces, but that preparation is not commonplace these days.

The areas of Papaloapan and Usila in La Chinantla Baja have their own local chiles, confusingly referred to as paisanos, criollos secos, and tabaqueros. The latter, according

to the experts, are also known as chiltepes. They are used dried not only in the dishes of the Sierra Mazateca but also in the area of La Cañada bordering on the state of Puebla, usually in stews, sauces, soups, and piltes. They have a bright red, shiny thin skin and are very picante. Flourishing bushes of small round or elongated chilpayas can be seen outside restaurants or in home gardens around Tuxtepec to be on hand fresh for their very hot sauces or to be bottled in vinegar. During my stay in Yogopi in La Chinantla

Baja, the chile soledad was being cultivated on small plots of land. It is a narrow, dark green chile about 2 inches (5 cm) long and tightly packed with seeds. I am told it is very much sought after in the markets of Mexico City but not so popular when dried. In Yogopi, a sauce was prepared with a small round chile called cuerudo, named for its characteristic tough skin when fresh.

On another occasion, when stopping on my way up to Huautla de Jiménez, I was given a taco of pochicuiles and toasted chiles canarios. To my surprise, they were fruity and mild, whereas the same chile called perón or manzano in the states of Mexico and Michoacán--and even those I have tried in Jalapa, Veracruz--are searingly hot. In Huautla, they are cooked in pilte).

As in many parts of Mexico, there are a number of unclassified chiles criollos, or local chiles, and unless one arrives at the time they are harvested, it is difficult to

distinguish them all. Such was the case with those sold in the Nochistlán market; some resembled chiles de agua, but I was told they were grown in Santa Inés, not far away, along with small, round deep red chiles called canica, or marble. They are both used in sauces and broths, and the larger ones are stuffed. In other areas, there are small chiles growing wild or cultivated in pots on local patios. For instance, in San Pedro Huilotepec, en route to San Mateo del Mar in the Isthmus, I heard about--but it was not the season to see it growing—a chile called guiña shirunduu (its local Zapotec name, identified

by botanist Porfirio López).

Tehuantepec also has its chile criollo, used fresh when in season and dried in many local

dishes. Returning to the city of Oaxaca, I stopped off in the mountain village of San Pedro Totolapa to see chiles xigoles growing, which I had bought dried in the central markets of Oaxaca. The great Zapotec cook Abigail Mendoza makes her table

sauces either with fresh chiles paraditos--small, narrow chiles pointing upward, as their name implies--from plants growing in macetas (pots) in the patio of the family compound, or from dried chontales--which somewhat resemble taviches--which she

says come from Yalalag in the Sierra Norte.

Athough I have heard mention of a chile loco in the area of Huajuapan de León, I have yet to come across a dish there in which it is used. I suspect it is an invasion from neighboring Puebla, where I have seen it in markets there on many occasions.

This segment aired on January 13, 2011.