Advertisement

'Bunheads' Young Adult Novel: Ballet Isn't All Pink & Pretty

Swan Lake wouldn't be much of a ballet without the group of swans who dance behind the Swan Queen, in the corps de ballet.

Twenty-eight-year-old author Sophie Flack knows the life of a corps dancer well.

She was in the corps of the New York City ballet for nine years, and her first novel, “Bunheads,” is loosely based on her own struggle to break out of the corps and become a soloist.

A bunhead is a girl who is obsessed with ballet and always wears her hair in a bun, according to Flack.

And Flack's main character Hannah has moments of glorious dancing. But she and her "frenemy" in the corps, Zoe, work so hard to stay on the radar screen of the director of the fictional "Manhattan Ballet" that they hardly ever venture far from the almost windowless theater building. One dancer who starves herself to stay thin collapses in rehearsals, and Hannah's non-dancer boyfriend begins to wonder if ballet really is a cult. Ultimately, dreams are dashed, as author Sophie flack's dreams were in real life.

She was laid off in company budget cutbacks three years ago.

Here & Now’s Lynn Menegon caught up with Flack at the South Shore Ballet Theatre in Norwell, Mass.

Book Excerpt: 'Bunheads'

By: Sophie Flack

Chapter 1

My name is Hannah Ward. Don’t call me a ballerina.

Ballerinas are the stars of the company. They dance center stage under the spotlight, and they get their own curtain calls. Their head shots are printed in the program, with their names in large print. Me, I’m a dancer in the corps de ballet, just one of the dozens of girls who dance in graceful unison each night. My mother thinks I’m a star, but she’s biased.

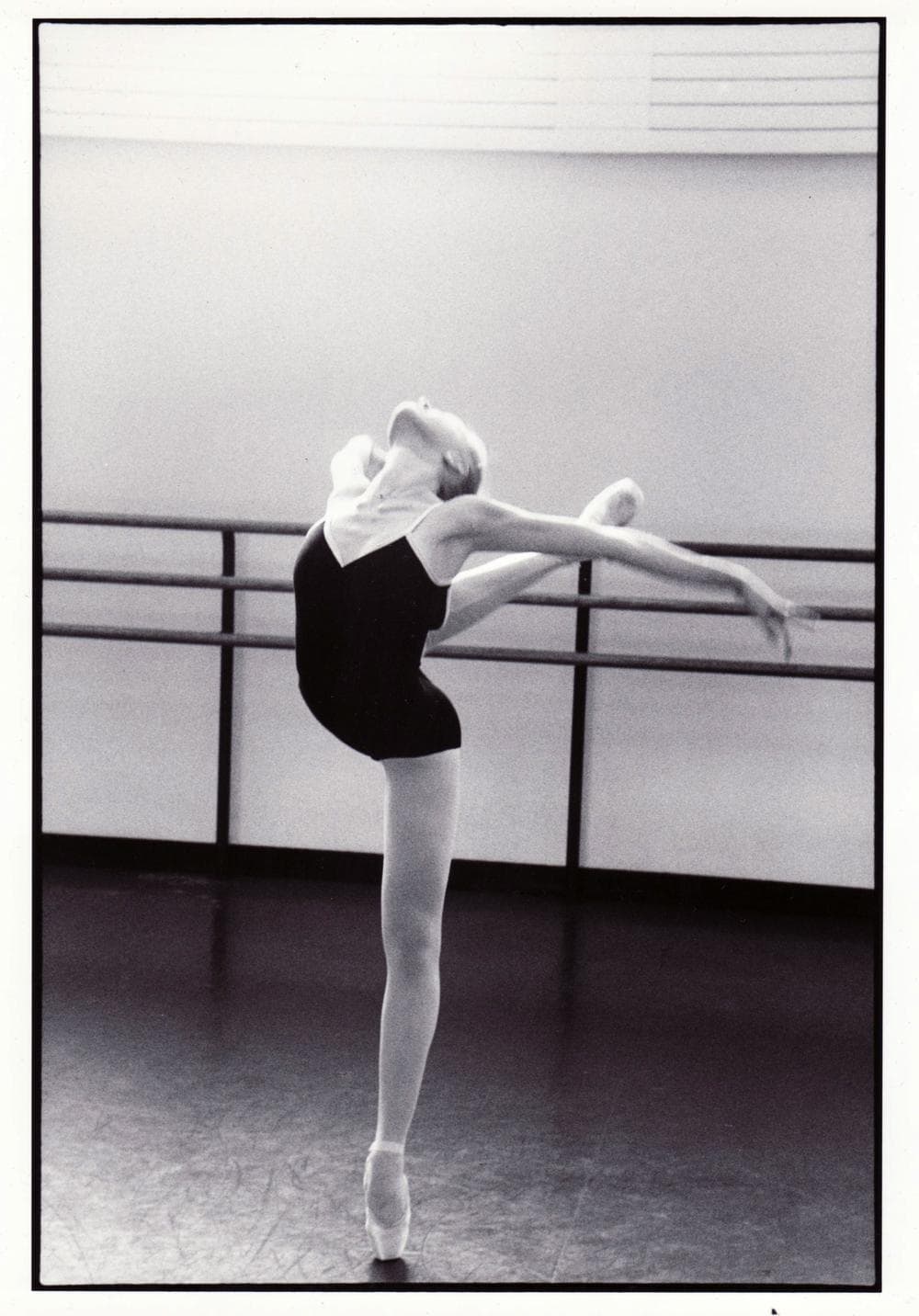

Besides, the word ballerina sounds too pink, too froufrou. Yes, we wear tutus and tiaras, but only when we perform each night. We spend most of our time hidden from the audience, working as hard as we possibly can to strengthen and control our bodies so that when we step onstage, everything we do looks perfect and effortless.

We rehearse in old leotards, threadbare tights, and torn leg warmers. We rarely buy new dance clothes because we know that most ballet careers are short-lived. Today, for example, I’m wearing a faded navy cotton leotard and black, slightly less faded leggings. There’s nothing pink or froufrou about that.

“Throw yourself into your dancing now,” one of my teachers once said, “because the life span of a dancer can be as short as a fruit fly’s.”

Advertisement

* * *

“Five minutes to curtain, ladies. Let’s shake a leg!” Christine, the stage manager, stands in the doorway with her hands on her hips. Her headset crackles, and she hastily barks something into it, then turns back to us. “Adriana, you don’t even have your shoes on. Am I going to have to hold the curtain?

Adriana wrinkles her pointy, powdered nose and holds up her shoes, plus the needle and thread she’ll use to sew herself into them. “See, I’m doing it,” she responds. “Anyway, there’s plenty of time. I have the whole overture.”

Christine smiles then, looking affectionate but also a little tense. It’s her job to make sure that every performance of the Manhattan Ballet goes the way it should. This means worrying about everything from the placement of the spotlights to the egos of prima ballerinas. With one last glance at us, she turns and scurries out, her short, platinum blond hair sticking up in all directions. “Places,” she calls.

I sympathize with Christine: It looks chaotic in here. We’re backstage in the Green Room before a Friday night performance, and all around me dancers are being fastened into their pristine white tutus. The room is a tangle of satin, tulle, and long, lean limbs. Some girls look deep in thought, while others chat loudly with one another. On the floor are discarded bits of clothing, lone pointe shoes, leg warmers, and half-empty water bottles.

“I took, like, eight Advil today,” a dark-haired dancer named Olivia says as she smacks her gum. “I hope I don’t die before the curtain comes down.”

“You’d better not let Christine see that gum or she’ll grab it right out of your mouth,” Adriana says as she sews into her pointe shoes. Her legs are long and almost skeletally thin.

But as I step into my own circle of ridged white tulle, I leave the chaos behind. It happens every time I dress for Waltz Variations: I feel as if I’ve time-traveled to a past, more glamorous era. Fake diamonds drip down my sternum, and my false eyelashes seem as large and as dark as butterfly wings.

Laura, one of the dressers, fastens the hooks on my bodice as I pull on my ivory gloves.

As soon as my costume is secure, I scurry out through the Green Room curtain and into the hands of the hairdressers. My friend Zoe is already there, impatiently tapping her foot in its pink pointe shoe.

“Hurry,” she growls as a flustered hairdresser attaches a diamond headpiece to Zoe’s pale blond bun. “No, that’s not it!” She pushes the hairdresser’s hand away.

Because there’s hardly any time, I decide to secure my headpiece myself. And apparently Zoe has decided to do this as well, because she shoves the hairdresser out of the way and steps in front of me, blocking my view of the mirror.

“I’m on before you,” I tell her, but she’s too busy with her bobby pins to listen. I place the diamond-encrusted tiara around my bun while trying to peer around Zoe, who refuses to relinquish her place before the mirror. I stab myself in the scalp with a bobby pin. “Ouch,” I yelp. Then I sigh loudly. “Z,” I say, “you know, you’re totally in my way.”

“What? Oh, hi, Hannah.” Zoe whirls around as if she’s only just noticed me. Her green eyes feign surprise. Her mouth, like mine, is full of clips and pins.

“Hi,” I say, putting my hands on my hips. “Do you mind?”

Zoe grins, turns back to her reflection, and scoots about a quarter of an inch to her left, so now I can almost see myself in the mirror.

Just as I get the tiara fixed, I hear the intro to my music. I run down the dark hall toward the stage, a piece of loose blond hair trailing behind me. I tuck it up into my bun and cross my fingers that it stays. My partner, Jonathan, is waiting for me in the darkened wings, a reassuring smile on his strong, handsome face. I lean back into his arms and allow him to support my back as he lifts me into the bright lights of the stage.

There I join the dozens of corps dancers, and as we swirl together, it seems as though we are an undulating sea of white. I am lifted off my feet, and it feels like flying.

“Whee!” I exclaim to Jonathan, who giggles.

Above us, chandeliers illuminate our twirling bodies, and I wonder if this is what a prom must be like. I didn’t go to my prom, because I was already performing with the Manhattan Ballet. I’ve seen Pretty in Pink and 10 Things I Hate About You, though, so I can imagine it well enough: There would be limos to ride in, and hidden flasks of liquor; the girls would be dressed in strapless satin gowns, and the boys in rented tuxedos. They’d slow-dance under spinning multicolored lights and make out in dark hallways.

Sometimes I think I must have missed something great. But then I tell myself that things experienced onstage are usually more exciting than things experienced in real life anyway.

The music swells, Jonathan lifts me again, and there’s a surge of applause as Lottie, the aging star of the Manhattan Ballet, enters stage left, her auburn hair in a slick, tight twist and diamond studs sparkling in her ears. I can’t see the audience in the darkened house, but they’re out there in their velvet-cushioned seats, watching us with anticipation and delight.

And I don’t feel like a teenager onstage—I feel like a princess waltzing with her prince.

* * *

I wanted to be a dancer for as long as I can remember. When all the other little girls in my neighborhood were riding around on their pink-tasseled bicycles or comparing the latest fashion accessories for their Barbies, I was taking ballet classes at the local studio and fantasizing about dancing the role of Marie in The Nutcracker.

Every day after school, my mom would pick me up and drive me to dance classes in Boston. I’d change into my leotard in the backseat of our minivan and do my bun in the mirrored sun visor. I didn’t fit in with the other kids at school, but when I got to the studio, I felt completely at home. I loved the discipline of the practice: There was always some step to improve upon, some position to perfect. And the adrenaline rush I got from dancing—it was intoxicating.

When I was ten, I told my mom that I was going to be a professional dancer. Instead of smiling and patting me on the head, as if that was just another silly idea from a headstrong fifth grader, she took me seriously. Maybe that’s because she’s an artist herself—a pretty successful ceramicist, to be specific—and so she values the creative impulse over just about anything else.

We began taking road trips to New York City so I could train with some of the best coaches in the country. The summer I turned fourteen, I studied at the Manhattan Ballet Academy, and when August came I was invited to enroll full-time. It was an amazing opportunity, a dream come true. The hitch? It meant moving to New York—alone.

My parents weren’t thrilled at the prospect: My mom worried that I was too young, and my dad worried that I’d get mugged. They had qualms about the academy dorms—were the doors locked at all times, were the floors coed?—and they wondered whether the high school I’d attend, the School of the Arts, offered classes in creative writing, my favorite subject. They realized that, even after I’d made it so far, there was still no guarantee that I’d actually become the professional I wanted to be. That’s why I had to tell them, over one of my mom’s hippie dinners of baked tofu and mashed yams, that this was the chance of a lifetime and that I was willing to take the risk.

I could see them struggling with the idea as they chewed (though my dad may have been struggling with his dinner, too; he’d never liked tofu). They understood that I’d be miserable if I stayed home in Weston, Massachusetts—that every day I’d wish I were at the academy, working toward a chance to be a part of the Manhattan Ballet, which was one of the best companies in the world.

After a few moments I saw my dad nod his head, ever so slightly. My mom turned to me, and her smile was happy and sad at the same time. “All right, then,” she whispered.

Today, five years later, I’m a senior corps member with the Manhattan Ballet. We perform three to four ballets a night to packed houses in New York City, and when we go on tour, our audience can fill five-thousand-seat amphitheaters.

I’m a ballet dancer, but I’m not a ballerina. And it’s the most amazing, wonderful, and crazy life I ever could have imagined.

Copyright © 2011 by Sophie Flack

This program aired on February 17, 2012.