Advertisement

After The Steroid Scandal, Father And Son Learn To Love Baseball Again

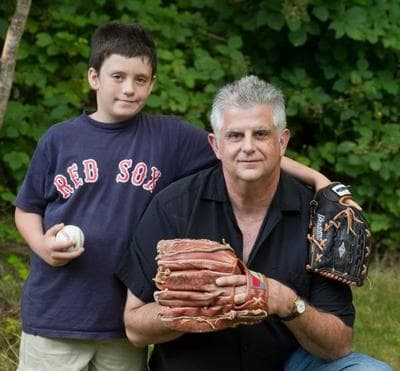

Freelance writer Jim Gullo loves baseball and he wanted his son Joe to love it too.

So, in the spring of 2007, he bought seven year-old Joe a glove, a bat and a ball, and got him started collecting cards where they lived on Bainbridge Island near Seattle.

It worked. Before long Joe couldn't stop peppering his dad with questions: "Who was better? George Bell, Albert Bell, or Rico Carty?" And, "Should Albert Pujols be in the Hall of Fame?" Or, "Can the Mariners trade for Red Sox slugger Manny Ramirez?"

Then in December, the Mitchell Report named 89 players likely to have used steroids and other performance enhancing drugs and Joe's questions changed: "It says that baseball players took drugs to make them better?" And, "Isn't it cheating?" he asked.

Joe also wanted to know if the players who took drugs would be punished. But his dad didn't have any answers — so the two went looking for them.

The result is a physical and emotional journey that Jim chronicles in his new book, "Trading Manny: How a Father and Son Learned to Love Baseball Again."

Book Excerpt: 'Trading Manny: How a Father and Son Learned to Love Baseball Again'

By: Jim Gullo

BASEBALL CARDS

December 13, 2007

Dear Manny. Hi, it’s Joe. What was it like to win the World Series? I thought you were amazing. You were my favorite player ’cause you were powerful. And on a histerically [sic] great team. Bye. Sincerely, Joe.

—JOE’S FIRST LETTER TO MANNY RAMIREZ, NOVEMBER 2007

“DAD, DID MO VAUGHN take steroids?” Joe called out from the living room, where he lay on the floor with his collection of baseball cards. It was twelve days before Christmas 2007, and he had just heard about the Mitchell Report, which named eighty-nine major-league baseball players, from stars like Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds to average players like Glenallen Hill, Vaughn, and Ron Villone, as likely to have used steroids and/or other performance-enhancing drugs over the past ten seasons. Joe, who was seven and a half years old, had heard about it on TV, and was now figuring out a new way to sort his cards. In the past he had made lists of great second basemen, Seattle Mariners, National League All-Stars . . . Now he was trying to separate out the juicers.

Advertisement

“Yes, according to Senator Mitchell’s report, he took drugs,” I called back from the kitchen. I would have rather been outside playing ball with him, but the weather had turned bad, and the horse pasture where we played catch was a muddy mess. The Pacific Northwest skies were as gloomy as baseball had become. To make do, during breaks from sorting his cards, Joe stood on one side of the room and hurled fastballs with a soft, plush ball into the brown leather couch. The ball made impressive cracking sounds as it hit the leather and I proudly thought, as 10 million other dads before me have thought of their sons and daughters, “The kid has an arm!”

“Did Wally Joyner take steroids?”

“Yes.”

“Kevin Brown?”

“Uh huh.” I was suddenly getting really frustrated with baseball. I didn’t have a clue what to tell my son. Bud Selig, the lovably hapless and (dare I say it) bumbling Commissioner of Major League Baseball announced that day that he hoped the Mitchell Report would set the drug issue to rest and we could all move on. But I could see that, at least in my little baseball-loving household, we hadn’t even begun to witness its effects.

When I tucked Joe into bed that night and read him a story (Honus and Me, about a boy traveling through time to meet Honus Wagner) and kissed him good night, he pointed to the poster of Manny Ramirez on his wall.

“Did Manny take steroids?”

It was with a great deal of relief that I said, “No, as far as we know, he didn’t.” Manny hadn’t been named in the Mitchell Report. Even though the Red Sox were three thousand miles away, he was Joe’s favorite player.

“That’s good . . . Dad?”

“Yes?”

“Isn’t it cheating? Those players who took drugs are going to be punished, right?”

I wanted to tell him yes, that the game we loved would be cleaned up and could go back to being, well, baseball. The greatest game ever. The game that had eaten his daddy’s summers for as long as I could remember. The game that had given us (just to name a few) Tom Seaver, Albert Pujols, Derek Jeter, Fred Lynn . . . and Bombo Rivera. “I hope so,” I said. “We’ll have to wait and see.”

“Because if they took drugs to make them play better, they were cheating,” Joe said. It was crystal clear to him what should happen to ballplayers who took performance-enhancing drugs. “They shouldn’t be allowed to play anymore.”

I remember thinking at the time, I wish it was that obvious to me.

“And Dad?”

“Last question, Joe.”

“Okay. Isn’t it really bad for you to take steroids? And if the players were already really good, why would they take them?”

IT WOULD TAKE me nearly two years from that night—two years of searching and asking my own questions—before I could fully answer Joe’s questions. Two seasons of searching from the bushes of baseball to Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park to tell my son why major-league ballplayers at the top of their games took steroids. And why he shouldn’t if he’s ever faced with the same decision.

It wasn’t a search that baseball encouraged, and nobody paid me to do it. But I was damn well going to find out why those players in the Mitchell Report took steroids, and who I could present to my little boy as a legitimate baseball hero. For Joe’s sake and my own, it was a journey that I had to take. My only other choice would have been to give up baseball altogether, which at one point I tried to do. Luckily, it didn’t work.

This isn’t your typical baseball book. I am, in a sense, a ballplayer, but I can’t throw a ball ninety miles an hour (just over half of that, which I was shocked to learn). I have warning track power at the plate, and I’m no Rickey Henderson: It takes me about five minutes to run around the bases these days, as I need to stop and rest at third. I’ve been in and out of a few major-league clubhouses during my twenty-plus years as a freelance magazine writer, and I have a few stories to tell from those hallowed places, but I can’t claim inside knowledge of what makes Albert Pujols tick, or the Meaning of Ichiro, or how in the world the Rangers got to the Series in 2010. But I do have lots to say about how a father (me) helped his little boy (Joe) through what may just be the most notorious period in baseball’s history. I’m just a fan of the game, like you. And like so many of you who have held a quiet disgust for baseball over the past five or so years—a bad taste in the mouth that lingered even as we continued to buy the mitts for our kids, and went to the games, and watched the Series in the fall—I wanted some answers from baseball. I wanted the game that I’ve loved since childhood to be made right.

That night in 2007 after the Mitchell Report came out, I tucked Joe in and kissed him. “Go to sleep now, son,” I said. “Tomorrow’s another day.”

His questions lingered in my mind late into the evening: Isn’t it cheating? Those players who took drugs are going to be punished, right?

Even a seven-year-old knew that. And I realized that Joe was absolutely right. It was cheating to take drugs to play better, or prolong a career, and it cheated all of us: the fans, the other players, Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, high school and college kids who wanted to “move up a level.” Me. Joe. You. If I was going to be a good father who taught my young son values, this was an obvious place to start.

Over the course of this journey, I was able to teach Joe a few things about right and wrong, and playing a game for the love of it. We were reminded that baseball is just such an awesome thing, woven into the very fabric of our American lives. Not to mention woven into the fabric of me, his dad, since I was seven years old.

To return the favor, Joe taught me something too.

While I was looking for answers about steroids, he taught me how to be a better father.

Chapter One

JOE

June 2007

Katie Couric: For the record, have you ever used steroids, human growth hormone, or any other performance-enhancing substance?

Alex Rodriguez: No.

Katie Couric: Have you ever been tempted to use those things?

Alex Rodriguez: No . . . I’ve never felt overmatched on the baseball field. I’ve always been in a very strong, dominant position.

—60 MINUTES INTERVIEW, DECEMBER 2007

When I arrived in Texas in 2001, I felt a tremendous amount of pressure.

—ALEX RODRIGUEZ, EXPLAINING WHY HE HAD TAKEN STEROIDS AS A TEXAS RANGER FROM 2001 TO 2003, ESPN INTERVIEW, FEBRUARY 2009

ON JUNE 18, Joe’s seventh birthday—six months before he would begin to sort his baseball cards in a unique, new way—I worked things just right and made my second son fall head over heels in love with baseball. He got a new ball and bat, a promise to go see the Mariners play at Safeco Field, his first box of baseball cards, and a PlayStation game that, miraculously it seemed, brought real players with whom he could play into our living room. By the third day he had figured out that nearly any lineup he drafted could beat the daylights out of the Kansas City Royals. By the fifth day he began to greet us at the breakfast table with sage baseball observations like, “Travis Hafner is a good hitter, but he has a very small head.”

My son, in short, was on his way toward a lifetime of crazed baseball fandom, just like his dad. The plan that I had been carefully formulating since before he was born—really, before I even met my wife Kris—had worked. Joe’s brother Mike—eleven years older and in college by the time this story takes place—was a basketball player, and still is, but in Joe I had found and groomed my baseball companion for life.

So I pulled out my old baseball books and sat Joe down, and over the course of that summer, before he even knew how to tie his shoes, my little boy learned nearly all at once about Babe Ruth, hook slides, bunting, the hidden ball trick, Jackie Robinson, why Ted Williams was “The Splendid Splinter,” the ’69 Mets, and how to stare down a batter and glower like Randy Johnson. I taught him all of those things. We played catch in the backyard, we pitched to each other, we went to games, and we argued over things like who was better: Frank Thomas or Jim Thome. I always came down on the side of the Big Hurt.

“Are you nuts?” Joe screeched at me. “Thome’s, like, incredible. He might break the all-time homer record before he’s done!”

I argued back, but playfully. Inside, I was thrilled. I had created my own little stats-chewing, side-taking, Yankees-damning, t’row dem bums out! baseball nut.

WE LIVED IN a rented farmhouse on Bainbridge Island, Washington, in the middle of Puget Sound and as far away from New York as you can get in the continental United States and still hate the Yankees. Bainbridge was a community of 22,000 people, with four stoplights on the entire island, a half-dozen nicely manicured ball fields, one bridge connecting us to the outside world, and a ferry boat that brought us into downtown Seattle to watch the Mariners get clobbered, year after year. Joe and I played ball in the vacant horse pasture next to the rented farmhouse, sometimes by ourselves, sometimes with the other kids on the street and their fathers. One apple tree served as first base and another as third in our makeshift diamond, and the split-rail fence that kept the horses in made a fine home-run barrier for our games.

Advertisement

A week after Joe turned seven, we were playing catch in the pasture on one of those fine summer evenings that linger slowly into dusk. “I’m Randy Johnson. This is my fastball,” said Joe. “Who are you, Dad?” He was growing up before my eyes, fast and all of a sudden. Our games of catch in the backyard actually became games of catch, rather than games of throw a ball wildly and wait until it stopped rolling to pick it up and throw it wildly again. Joe threw righty and I had taught him how to bat lefty, which he did with a nice, uppercut stroke. He was and still is a skinny, chatty little guy with big hazel-colored eyes and a mop of brown hair that looks like a crowd at a movie theater rushing for the exits.

As Casey Stengel once said of a promising rookie, “I got this kid here, twenty years old, and with the way he can hit and throw in ten years he’s got a good chance to be thirty.” In ten years, Joe had a chance to be a pretty good high school ballplayer, and for selfish reasons I wanted to play as much pitch and catch with him as I could before I got too old. I haven’t played a game of tackle football, thankfully, since high school. Basketball lasted until I was forty-two before my knees said, No más. But at fifty-one years old, I could still throw a ball with some zip and hit it over the horse pasture fence in a way that made Joe’s jaw drop and made him exclaim with wonder, “Dad, you creamed it!”

In fact, I was enjoying one of those autumn-of-the-career seasons of which every ballplayer dreams. Thanks to my good hands and an incredible dearth of talent on Bainbridge Island, I was asked to play shortstop on a co-ed softball team, the only time in my not-so-storied baseball career that I’ve ever gotten to play the position of Ripken and Ozzie Smith and Omar Vizquel. Such was my range that any ball hit within three inches of either side of me was a sure out; backhanding a ground ball, feeling it thump into the pocket of my mitt, and whipping a strike to first base was practically a religious experience for me. And I could still hit: On my first at-bat of the season, I pulled a ball so hard and far to left that even the mothers on our bench—respectable pillars of the community, all, and members of the PTA—were heard to exclaim, “Holy shit!” I made it all the way to third before running out of breath.

Now Joe was going into his Randy Johnson wind-up as I crouched down as best I could. “I’m Yogi Berra. Now bring me the heat,” I said. Joe always wants me to be someone I’m not when we play catch, and I figured I had a better chance of catching his fastball if I were Yogi Berra. But then Joe threw it over my head. Slowly, stiffly, I stood up and turned to retrieve it. Like Yogi himself, I’m getting too old to be the catcher.

“Sorry, Dad,” Joe said before adding, “I was thinking that when I become a major-leaguer, I’ll start off by playing for the Mariners so that you and Mommy can come and see me every night. And then I’ll play for the Red Sox.”

“That’s very thoughtful of you.” I wondered who was going to bathe him, read him stories, and tuck him in every night when he was with the Red Sox, as his mother still does at our home. Terry Francona? Papelbon? I think not. I’m obviously not ready to even entertain thoughts of Joe ever moving away from us. He may just be the sweetest boy ever made.

“Okay, now I’m CC Sabathia,” said Joe when I threw the ball back. “Who are you?”

“Campanella.”

“Roy Campanella?”

“Darn right, Roy Campanella.”

“He was good, wasn’t he?”

“Are you kidding? He was great.”

Joe wound up and threw, and the ball landed in my mitt with a satisfying crack of leather. He paused when I threw the ball back, collecting his thoughts.

“Dad, I was thinking that maybe you and Mommy could go to the movies one night,” he began.

This came as something of a surprise, because Joe rarely let his mother out of his sight in the evenings, and it was a rare night when Kris or I didn’t tuck him in.

“And who would watch you?”

He shrugged, trying to look nonchalant. “I was thinking maybe Ichiro could. Or Raul.”

We had seen Suzuki and Ibanez—two of the Mariners’ outfielders—play the previous week, and Joe figured out for himself that they were good babysitting material. I didn’t quite know how to tell him that they made about $28 million a year between them and probably had little need for the twenty bucks and plate of cookies that we could afford to pay a babysitter.

“I’ll see what I can do.”

WE HAD READ the books and gone to games and played a lot of pitch and catch, but it was the PlayStation game and the box of baseball cards that really hooked Joe that summer. He played the videogame relentlessly, waking us up from the living room at six o’clock to the sound of the game’s announcer shouting, “It’s gone!” He pored over the cards, memorized the statistics of the players, and began to make lists: of .300 hitters, relief pitchers, Hall of Famers. He burst into rooms and interrupted conversations to tell us that Eddie Murray had 124 RBIs in 1985.

And he asked a million questions, some of them astute—“Who was better, George Bell, Albert Belle, or Rico Carty?”—and some of them really dumb: “Was Sandy Koufax any good? Do you think Mike Lieberthal should be in the Hall of Fame?” Not a day went by that Joe didn’t begin a frank and earnest discussion about Albert Pujols. Was he good? Would he be in the Hall of Fame? Did I know how many doubles he hit last year? Would I like to be reminded? Sometimes I’d answer Pujols questions for five minutes, and a half hour later Joe would come to my office and ask the same questions again. He just really wanted to talk about Albert Pujols.

Capping it all off was a poster of Manny Ramirez, Joe’s favorite player, placed carefully by a little boy in the A-position at the head of his bed, where it was the first thing he saw in the morning and the last at night. It showed a powerful young man in a Red Sox uniform, muscles bulging and dreadlocks flying as he socked a pitch with a devastating swing. He was a modern-day superhero, and after years of fending off Joe’s Pokémon and Marvel characters and Dragon Ball Z action figures, sneakily replacing them with baseball books and stories about Mickey Mantle, I was happy to let Manny be Joe’s role model.

In retrospect, this was perhaps not my brightest parenting decision of the last decade.

IT WAS THE last summer for years that baseball would be lovable, but I can see now that dark clouds were already roiling on the baseball horizon. As the Seattle summer eased into the fall of 2007, we watched on TV as Barry Bonds broke Hank Aaron’s career record for homers. With Joe sitting next to me, I found myself torn. There was widespread speculation that Bonds had achieved his physique and great power through massive use of performance-enhancing drugs. But the guy had the sweetest swing in the world and I loved watching him hit.* He absolutely demolished any pitches opposing pitchers dared to throw for strikes. Should I tell my little boy to emulate and enjoy Bonds’s record-setting performance or turn the TV off? Instead, I ignored the question. Like so many other fathers and baseball fans, I really didn’t want to know. Don’t ask, don’t tell—baseball style. After Bonds hit the record-breaking homer, Joe frowned: “He didn’t even hug his kids when they came out to greet him at home plate,” he said. It was the first of many marks against Bonds that he would bring to my attention.

*Bonds, who has sworn to this day that he never knowingly used performance-enhancing drugs (emphasis on the key word, knowingly), had his day in court in April 2011. After much testimony from his former lover and several confidantes, who described either watching him be injected by his trainer or hearing Bonds complain about his injections, a jury found him guilty of obstruction of justice for lying about his use of PEDs. The same jury was hung on the questions of whether he knowingly lied about taking steroids or human growth hormone. Bonds appealed the decision.

MANNY LED THE Red Sox to a World Series crown that fall, their second since finally breaking the Curse of the Bambino in 2004. The great slugger broke the record for postseason home runs, first by hitting a walk-off three-run bomb to beat the Angels in Game 2 of the ALCS, going back-to-back with David Ortiz in Game 4 to take the Sox into the Series, and then hitting another in the Series win against the Rockies. Joe and I cheered for the BoSox with every pitch.

Halloween came a few weeks later, and the other kids out trick-or-treating on Bainbridge Island were dressed as the Thing, and the Scream, werewolves, witches, or Pokémon characters. Joe had his mom draw a moustache and beard on his face with a grease pencil, and pin a new name to the back of his Red Sox T-shirt. For Halloween, Joe was Josh Beckett.

When, puzzled, his friends pulled off their masks and asked Joe what he was, he coolly replied with one word: “Beckett.” Most of the kids had no idea what he was talking about.

At Thanksgiving, Joe wrote and mailed his first letter. It wasn’t to his grandmother or to the president. It was to the Boston Red Sox. “Congradulations [sic] on winning the World Series. I totally hate the Yankees,” he confided. “And I can’t believe that Beckett didn’t win the Cy Young.”

HE WAS SO pleased with his work that he wrote a second letter, to Manny, who, like Pujols, had become the topic of almost daily conversation around our house. When Joe cocked his little plastic Wiffle ball bat, he cocked it like Manny. When he schemed of ways to improve our hometown Seattle Mariners, it always included Manny.

At dinner one night, after a riveting discussion of spelling words and the necessity of good spelling in a polite, functioning society, Joe waited for our lips to stop moving and blurted out, “Wouldn’t it be great if the Mariners got Teixeira?”

I nervously looked at Kris; I knew she wouldn’t be much help in the ensuing debate. Her knowledge of baseball is spotty, and there was every indication that she thought Teixeira was a new kind of breakfast cereal, when actually, Mark Teixeira was the first baseman for the Atlanta Braves at the time.

“Why would it be so great if we got Teixeira?” I said.

Joe looked at me like I was an imbecile. “He’d hit, like, fifty homers and we’d be great.”

“Yeah, but I don’t think the Braves are going to let him go.”

“He’s like their best player now!”

“I know.”

He put his fork down with a buttered noodle still hanging on it. The kid could eat buttered noodles every night of his life. When we didn’t want to fight with Joe about eating vegetables or salmon, we made buttered noodles and everyone was happy. “I’m just saying that it would be really great to get him. He’d be a great first baseman for the Mariners.”

“So would I.”

Joe collapsed in laughter. He almost fell off his chair. “Oh, sure. Yeah. You’d, like, start to cry if Ichiro was running toward you. You’d just drop the ball and cry.”

“No, I wouldn’t,” I said quietly, my pride wounded. Aren’t kids supposed to think their old man can do anything? Hadn’t he hung on every word of the stories of my years as a second-string first baseman for Pocono Mountain High School, circa 1974? Well, actually, no he hadn’t.

Joe had another great idea. “What if we traded for Manny?”

I shook my head. We had been down this road before. I never won this conversation, and Joe brought it up nearly every day. I had told him over and over that nobody would be dumb enough to trade ordinary players—especially ordinary Mariners—for Manny Ramirez of the Boston Red Sox. Nobody. The Red Sox didn’t become World Series champions by being dummies.

“We’re not going to trade for Manny,” I said quietly. “The Red Sox would be crazy to give him up.”

“We would cream everybody,” Joe said triumphantly, picturing Manny hitting a million homers in Safeco Field and leading the Mariners to their first World Series championship. “It could happen,” said Joe, leaving the table and returning to his collection of baseball cards spread out on the living room floor.

No, it couldn’t, I said to myself, but for once I let Joe dream what he wanted to dream. He was building his own baseball world in his head, as I did when I was seven, and twelve, and thirty (the year that I was crazy enough to think that the Twins with Kirby Puckett and Burt Blyleven could win the World Series, and they did).

“Hey,” Joe called out from the living room floor, “what if we got Manny and Teixeira?”

THREE WEEKS LATER, the Mitchell Report came out, delivering the news of baseball’s dark secret of drug use. Suddenly, in about the amount of time it took a Bonds homer to leave the building and land with a plop into San Francisco Bay, everything changed for me and Joe. Our father-son fandom nearly ended before it even began.

Copyright Decapo Press.

Guests:

- Jim Gullo, freelance writer

- Joe Gullo, son of Jim Gullo

This segment aired on April 4, 2012.