Advertisement

Anne Lamott Updates Her 'Operating Instructions' After Becoming Grandmother

Back in 1993, author Anne Lamott, then a 35-year-old single mom, wrote a funny and unflinching memoir of her son Sam's first year. Called "Operating Instructions," the book became a bestseller and set the stage for contemporary parenting writing and the recent glut of mommy bloggers.

Time magazine calls her the "doyenne of the parenting memoir." Lamott, a left-leaning, recovering alcoholic, born-again Christian, is like a Dr. Spock for grandparents.

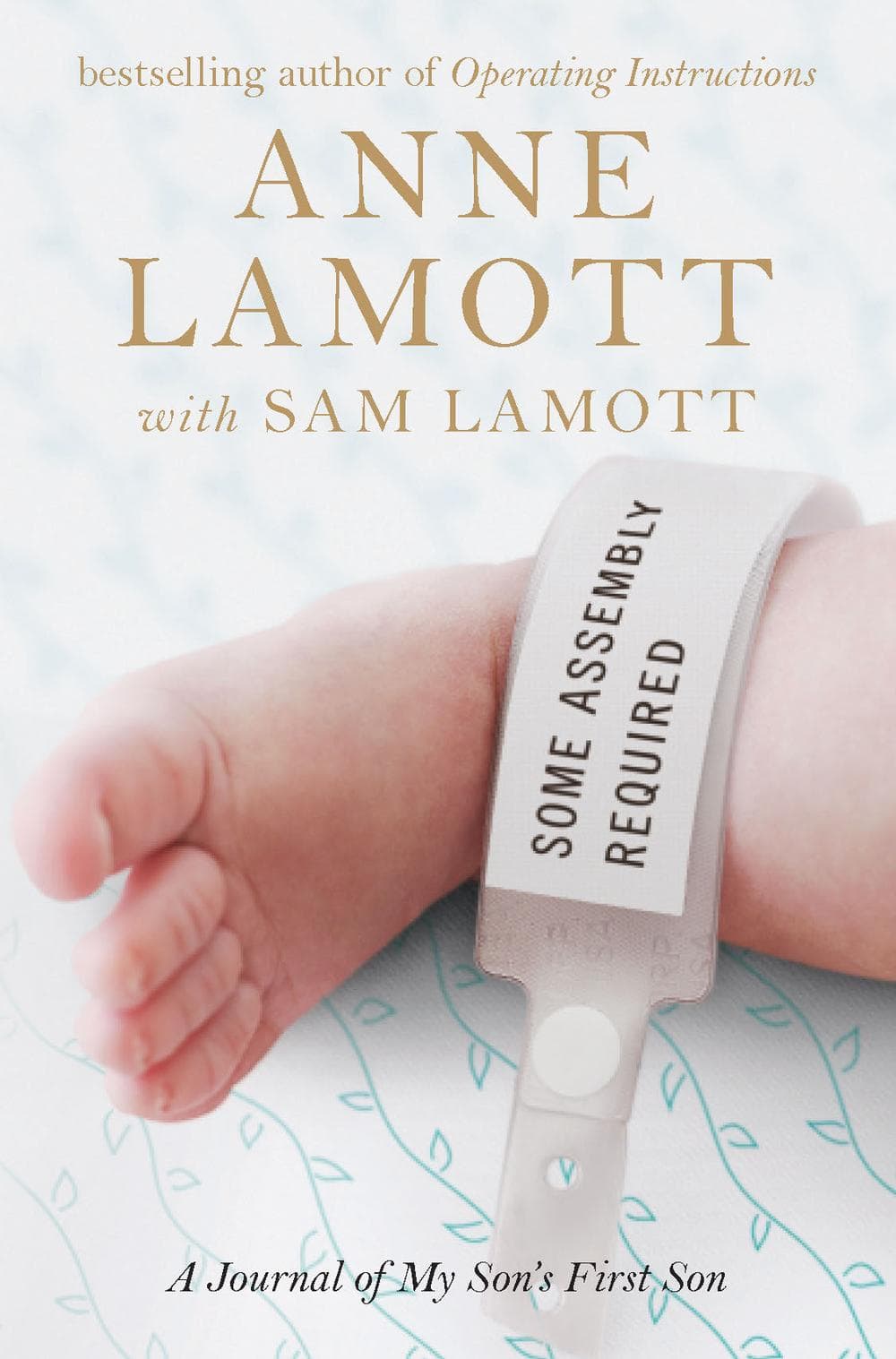

Two decades and several bestselling books later, Lamott writes a book with Sam, who is now a father. Which makes Lamott a grandmother. Her latest book, "Some Assembly Required: A Journal of My Son's First Son," chronicles her ups and downs as she navigates the new world of becoming a grandparent while Sam tries to figure out the owners' manual.

"Being a mother and being a grandmother is so much about prying your clutched fingers off of people's lives," she told Here & Now's Robin Young. "Not only that but agreeing not to run along beside him with my clipboard."

Book Excerpt: 'Some Assembly Required'

By: Anne Lamott

My very young son became a father in mid-July 2009, when his girlfriend, Amy Tobias, gave birth to their son. They named him Jax Jesse Lamott, Jesse after Amy’s beloved grandmother Jessie, and Jax because they liked the way it sounded. Amy was twenty when she delivered, and Sam was nineteen. They’re both a little young, but who asked me?

My very young son became a father in mid-July 2009, when his girlfriend, Amy Tobias, gave birth to their son. They named him Jax Jesse Lamott, Jesse after Amy’s beloved grandmother Jessie, and Jax because they liked the way it sounded. Amy was twenty when she delivered, and Sam was nineteen. They’re both a little young, but who asked me?Sam’s birth, on August 29, 1989, was by far the most important day of my life, and Jax’s was the second. Sam and I are quite close, and I’d always looked forward with enthusiasm to becoming a grandmother someday, in, say, ten years from now, perhaps after he had graduated from the art academy he attends in San Francisco and settled down into a career, and when I was old enough to be a grandmother. I was

a young fifty-five. Maybe a medium i fty-i ve. Let’s say a ripe fifty-five, with a child just one year past his majority.

The day before Thanksgiving 2008, I had heard that Amy was expecting, when I got a call from Sam, in despair.

Advertisement

“Mom, I’m going to be a father,” he said.

I was silent for a time. “Oh, Sam,” I said initially. He and Amy had been together, tumultuously, since his birthday a year earlier, but they had split up a couple of months before—although not, I can see now, in the biblical sense. Amy is beautiful, tiny and Hispanic, with her roots in Chicago and her parents now living in North Carolina. She had arrived in our lives on the morning of Sam’s eighteenth birthday, to attend cosmetology school in San Francisco: they had become friends at a camp on the East Coast, stayed

in touch by phone and text, and begun a long-term relationship, which I hadn’t heard about. One day Sam told me he’d offered her his living room couch until she found an apartment. “Right,” I said when he told me this plan: I was not born yesterday.

“God, Mom,” he had said. Like, get your head out of the gutter.

She had moved off the couch by lunch that first day.They arrived for Sam’s family party at my house at four that afternoon, very much in love. My brother Stevo, his sunny six-year-old daughter, Clara, and his i ancée, Annette, were there, as was our beloved uncle Millard, our aunt Eleanor, our best family friends, including Gertrud, a ninety-year-old German who’d always served as Sam’s paternal grandmother, and a scattering of cousins. We were all transfixed by this beautiful girl who bounced into the house, in tiny shorts that would i t my cat—she is around four-foot-nine, and weighed ninety pounds at the time—with long black hair, huge brown eyes, and a perfect smile; and my i rst thought was, “Whom did I invite who has a teenage Hispanic daughter?” I thought she might be related to Annette, who is also Latina. Then

Sam stepped inside, smiling sheepishly, and introduced Amy to me.

A little over a year later, Amy had terrible morning sickness that lasted a few months, and she spent a lot of time taking naps on my couch, and nibbling bird-sized snacks. I was happy all the time at the thought of Sam’s being a father, and my getting to be a grandmother, except when I was sick

with fears about their future, enraged that they had gotten themselves pregnant so young, or in a swivet of trying to control their every move, not to mention every aspect of their futures. She and Sam had moved back in together, into his tiny studio apartment on Geary, two blocks from his art school. Although Amy’s parents were contributing to her expenses, I was paying Sam and Amy’s rent. Amy frequently

escaped to my house in Marin, mostly for companionship, as Sam was in school full-time, but also for the sun and relative peace, as their apartment was dark and loud. By the time the morning sickness passed, her belly was huge, especially because she is—or rather was—so tiny. She had an elaborate space-age ultrasound at four months, which indicated that the fetus was a boy: the technician printed out Jax’s picture for us. He looked like a bright, advanced baby.

They moved into a one-room apartment a few blocks from the old studio, and created a nursery in a corner of the bedroom.

Sam was woozy with pride and scared to death. Amy was clear, calm, and fiercely into becoming a mother. She did things the way she wanted to, even when it made me unhappy. For instance, two weeks before her due date, she skipped a routine doctor’s appointment for some youthful, willful reason, and I spent several days pacing around my house, trying to make peace with the idea that now the baby would almost certainly be born with some degree of disability. I cried. Sam tried to protect Amy from my neediness and anxieties—i.e., they purposely didn’t call or text me for days. And they fought routinely. Amy would threaten to move back to Chicago, which made me crazier than anything, but I would not interfere, and Sam would call in despair, and I would stay neutral, with undertones of suppressed rage, and they’d come through their conl ict, and I would get to be the beloved tribal elder for having stayed impartial.

We went to our little church, St. Andrew, many Sundays, unless Sam had too much homework. The month before

Jax’s birth, Sam was both in summer school and working for a contractor, trying to sock some money away. I had promised him a four-year education, but even though he was contributing, it was more expensive than I had expected, and I had a nagging hunch that things were not going to become cheaper after Jax was born.

I had loved being pregnant with Sam, mostly: all the parental blessings of feeling accomplished, envied, completed, astounded, proud, grateful. And I loved Amy’s being pregnant with Sam’s baby, mostly. I was excited that Sam was going to have all these feelings for someone, too. It would be better for him in some ways than it had been for me; I had not had any money our i rst few years, and that had been hard.

And it could be only good for a baby to have two parents around. Yet having a child ends any feelings of complacency one might ever have, and I knew what Sam was in for. It was like having a terminal illness, but in a good way. I frequently got to put my hands on Amy’s belly and feel Jax roll and kick around in his chambers. She and I would take afternoon naps together on the two couches in my living room. She gained sixty pounds; I gained i ve. Her mother, Trudy, and I would get to be there at the hospital for his birth, which Amy passionately hoped to accomplish without drugs.

Her mother would l y in from North Carolina near the due date, and she and I spoke or texted from time to time, making plans for Amy’s hospital stay, and for just after. Amy, Sam, and the baby would come to my house from the hospital, along with Trudy, and then at some point Amy’s father, Ray, would come from North Carolina to stay for a few days. We would all be one big happy family, as Ray liked to say.

I prayed every day for a healthy baby, for an easy delivery, for Sam and Amy to be good parents, and for me to let God be in charge of our lives. I prayed to be a beneficent grandmother, and not to bog down in how old that made me sound. I had two slogans to guide me. One was: “Figure it out” is not a good slogan. And the other was: Ask and allow: ask God, and allow grace in.

July 21

Amy delivered late last night by C-section after eighteen hours of hard and heroic natural labor, at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, one of the nation’s great teaching hospitals, in the upper Haight-Ashbury, just beyond the southeast corner of Golden Gate Park. Sam had called me at two yesterday morning and told me to meet him, Amy, and Trudy at the hospital.

Trudy is i vefoot-six, an inch shorter than I am, brunette, and very sweet, a few years older than I. Her grandma nomenclature will be “Grammy,” and mine will be “Nana,” which is what Sam called my mother. Amy was given a private room, and was plugged into various monitors. Sam coached her for the first few hours, and then Trudy and I coached her, and then Sam again. After many hours, Amy was dilated to six centimeters, but she wasn’t getting any further. She refused any drugs for hours, even Pitocin to intensify the contractions, and watching her I felt crazy with powerlessness and thwarted Good.

Reprinted by arrangement with Riverhead, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from SOME ASSEMBLY REQUIRED: A Journal of My Son's First Son by Anne Lamott with Sam Lamott

Copyright © 2012 by Anne Lamott and Sam Lamott

This segment aired on April 11, 2012.