Advertisement

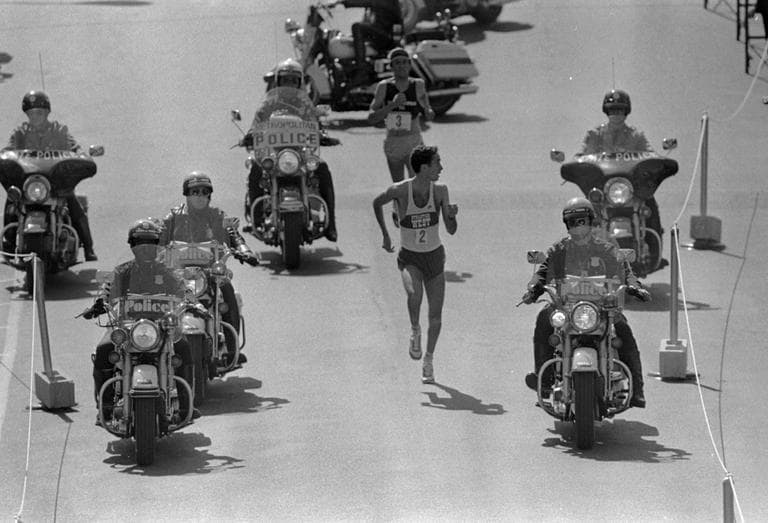

Marathon History: Remembering The '82 Battle Between Salazar And Beardsley

Resume

Every year ahead of the Boston Marathon, the organizers highlight races from the past.

This year they're marking the 30th anniversary of one of the greatest competitions in the race's more than 100-year history: The 1982 battle between Alberto Salazar and Dick Beardsley.

The two men ran neck and neck for the final nine miles of the race, with Salazar pulling ahead in the end and winning by just two seconds.

The race took an incredible toll on both men, a toll documented in John Brant's book, "Duel In The Sun," excerpted below.

- Boston Public Library: Alberto Salazar Speaks On Sunday April 15

- More Stories By Alex Ashlock

Book Excerpt: 'Duel In The Sun: The Story of Alberto Salazar, Dick Beardsley, and America's Greatest Marathon'

By: John Brant

Monday, April 19, Patriots’ Day, broke warm and blue over Boston, perfect for just about anything except running 26.2 miles. At a little after 7:00 a.m., Dick Beardsley stood at the window of his room at the downtown Sheraton, watching work crews ready the marathon’s finish-line area on Hereford Street far below. Behind him in the room, his wife, Mary, slept. He was glad to have her with him, but it also felt somewhat strange. Normally, when Beardsley traveled to road races, Mary stayed home in Rush City, Minnesota, where she worked as a secretary in an insurance office. But Mary had wanted to see the sights in Boston and support her husband at the crucial moment of his career.

Although it had lost some of its luster in recent years, the Boston Marathon remained the world’s most famous distance run, defining the sport for the general public the way Johnstown defined floods. Americans became horse racing fans on Kentucky Derby day and auto racing fans on Memorial Day for the Indianapolis 500; on Patriots’ Day (commemorating the battles of Lexington and Concord and the start of the Revolutionary War), they turned their brief attention spans to the Boston Marathon. Even Beardsley’s father in Minnesota knew about the race. When Dick had started running as a high school junior, his father had given him a special birthday present—an IOU plane ticket good one day for a trip to the Boston Marathon.

A decade later, Dick had finally made it to Boston for the marathon’s 86th running. His father, however, hadn’t paid a cent for the trip; the only thing Bill Beardsley was interested in buying was his next fifth of gin. Nor did the race organizers offer appearance or prize money (those emoluments wouldn’t come to the race for a few more years). New Balance, Beardsley’s shoe sponsor, was picking up his tab.

Tradition and prestige, not cash, had drawn Dick to Boston. Most big-city marathons, for instance, started early on Sunday morning. Boston, by contrast, always started at noon on Monday. Instead of getting out of bed and proceeding directly to the starting line, as was his custom, Dick now had 5 long hours to fill. He wasn’t hungry, but he knew he needed nourishment. He tiptoed to the phone and ordered toast and hot chocolate from room service.

As he nibbled the toast and sipped the cocoa, he watched the Today show, turning the volume down low so as not to disturb Mary. Willard Scott, the weatherman, predicted bright sunshine and a high of 75 degrees for the Boston area. “A great day for the marathon,” he said.

“Shows how much you know about the marathon, Willard,” Beardsley murmured to the screen.

Dick flicked off the TV and moved back to the window. His edginess transcended normal prerace jitters. He felt as if he were standing at a precipice, as if something momentous lay in store. By predilection and economic necessity, Beardsley liked to race nearly every weekend. Combined with his $25,000 annual stipend from New Balance, prize winnings from 10-Ks, marathons, and other road races earned him and Mary the semblance of a middle-class income. For the last 3 months, however, Beardsley had forgone the road-race paydays, sequestering himself in Atlanta, where he trained exclusively—and furiously—for Boston. Two weeks earlier, he had logged his last hard workout, 20 miles at 2-hour, 12-minute marathon pace over a hilly course. Later that day, he’d reported the results to his Boston-based coach, Bill Squires.

“I couldn’t feel my feet touching the ground,” Beardsley said. “I felt like I was flying.”

“You damn fool!” Squires screamed into the phone. “You just left your marathon in Georgia!”

But Beardsley knew he had plenty left in him. During training, he typically ran 120 to 140 miles per week, an average of just under 20 miles a day. In the 2 weeks before a marathon, when he cut that mileage to 70, he felt like he was barely running at all. He couldn’t sleep. The energy boiled out of him.

He pushed aside the cup of chalky hot chocolate and took a long drink of cold water. The only defense against the heat was to drink all morning, flush his tissues with water, and keep drinking all through the race. Maybe Salazar wouldn’t be so careful.

For a while, Dick sat in the chair, his feet up on the table, by turns watching the TV and the morning light rising on Hereford Street. He sipped water, made frequent trips to the bathroom, and, as he’d been doing continuously for the last month, thought about Alberto Salazar. On Thursday night, Dick had watched on the TV news as Salazar arrived at Logan Airport.

“There’s no other runner here who especially concerns me,” Salazar had told the reporters. “If de Castella or Seko were competing, it would be different. But looking at the rest of the field... Let’s just say I’m fit and prepared. If there are no injuries or unforeseen developments... Well, the facts are plain; I’m the fastest man in the race.”

There was no disputing Salazar’s facts: He was clearly the fastest man in the race. For the last few years, he had been the fastest man in just about any distance race on earth. Salazar owned the world record in the marathon—2:08:13.He was the two-time defending champion of the New York City Marathon. On the track, he was the second-fastest American ever in the 10,000 meters and a member of the 1980 Olympic team.

He’d been an NCAA cross-country champion and last month, in Morocco, had finished second in the world cross-country championships. The state of Salazar’s present fitness was daunting; just 9 days earlier, he’d run 27:30 for 10,000 meters, 2 seconds off the American record and almost 2 minutes faster than Beardsley’s best for that distance. Salazar, moreover, was handsome and charismatic, the closest the sport of running came to a household name. After his world-record performance in New York City last autumn, Sports Illustrated published a long, adulatory profile of him. President Ronald Reagan congratulated Salazar at a ceremony at the White House.

Beardsley had run against him once before, at the 1980 New York City Marathon, Salazar’s debut at the distance. Then a 22-year-old senior at the University of Oregon, Salazar had swaggered into the media capital of the world and publicly announced that he would run the race faster than 2:10, the standard for a world-class marathon. At the time, Beardsley’s personal best for the distance was 2:12.All through race week, he watched Salazar cut around Manhattan in a black leather jacket, looking like a young Montgomery Clift.

“Alberto wasn’t exactly bragging; he was just extremely confident,” Beardsley recalled. “He had already trained with Bill Rodgers, who was the reigning champion of the marathon, and he knew that he was in just as good of shape as Billy—in fact, a lot better shape. He didn’t predict victory, just that, if the day went reasonably well, this is how he would perform. It’s not really bragging if you back it up.”

On the day of the marathon, Beardsley broke fast from the start on the Verrazano Narrows Bridge and by midrace had established a significant lead over the rest of the pack. He held the lead through the 18-mile mark, which came at the Manhattan end of the Queensboro Bridge. When Beardsley swooped down from the bridge, which was closed to spectators, the roar from the crowd lining First Avenue nearly staggered him. Bill Squires, who had recently begun coaching Beardsley, stood among the crowd. He was shocked to see his runner so soon. “Holy shit, Dickie!” he screamed. “You’re leading the New York City Marathon!”

It seemed too good to be true, and it was. Just beyond the bridge, Salazar blasted past Beardsley without a glance, gliding on to a commanding 2:09:41 victory. Salazar had logged the fastest debut marathon ever and delivered the time that he’d promised. Beardsley, meanwhile, faded to a ninth-place, 2:13:55 finish. As close as he’d come to Salazar, however (at the finish, roughly two-thirds of a mile separated them), he might as well have been 90th.

So what would be different here in Boston 18 months later? Everything, Dick vowed. “My whole life boiled down to this,” Beardsley would remember in his autobiography. “One way or another, this race would change everything....I was a runaway train. That’s how it felt. My times were getting so much better so much faster, I had no idea where it would lead.”

Excerpted from "Duel In The Sun: The Story of Alberto Salazar, Dick Beardsley, and America's Greatest Marathon," copyright Rodale Books, 2007.

This radio story originally broadcast in 2006.

Guest:

- John Brant, author

This segment aired on April 13, 2012.