Advertisement

Walter Dean Myers Shows Kids How To Succeed Under Tough Circumstances

Growing up in Harlem in the 1940s, Walter Dean Myers didn't have it easy.

His uncle was murdered when he was 14, sending his foster father spiraling into deep depression and alcoholism, and bringing down the entire family — and Myers' chances of going to college.

"I started to understand that even though I was good at school and loved to read, college wouldn't be a possibility for me," he writes. "My family could barely afford to keep me in high school."

"I am determined to use my life as a template for these kids. If I can do this, so can they."

Author Walter Dean Myers

Myers was soon getting into trouble with the police regularly and he eventually dropped out of high school.

So how did he become one of the most respected writers of young adult fiction?

Nurturing A Love Of Books

Despite the chaos around him, Myers was able to nurture his love of books in the George Bruce Branch of the New York Public Library on West 125th street, immersing himself in French novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac and novelist Ernest Hemingway. He also took to heart advice from a teacher to "keep writing."

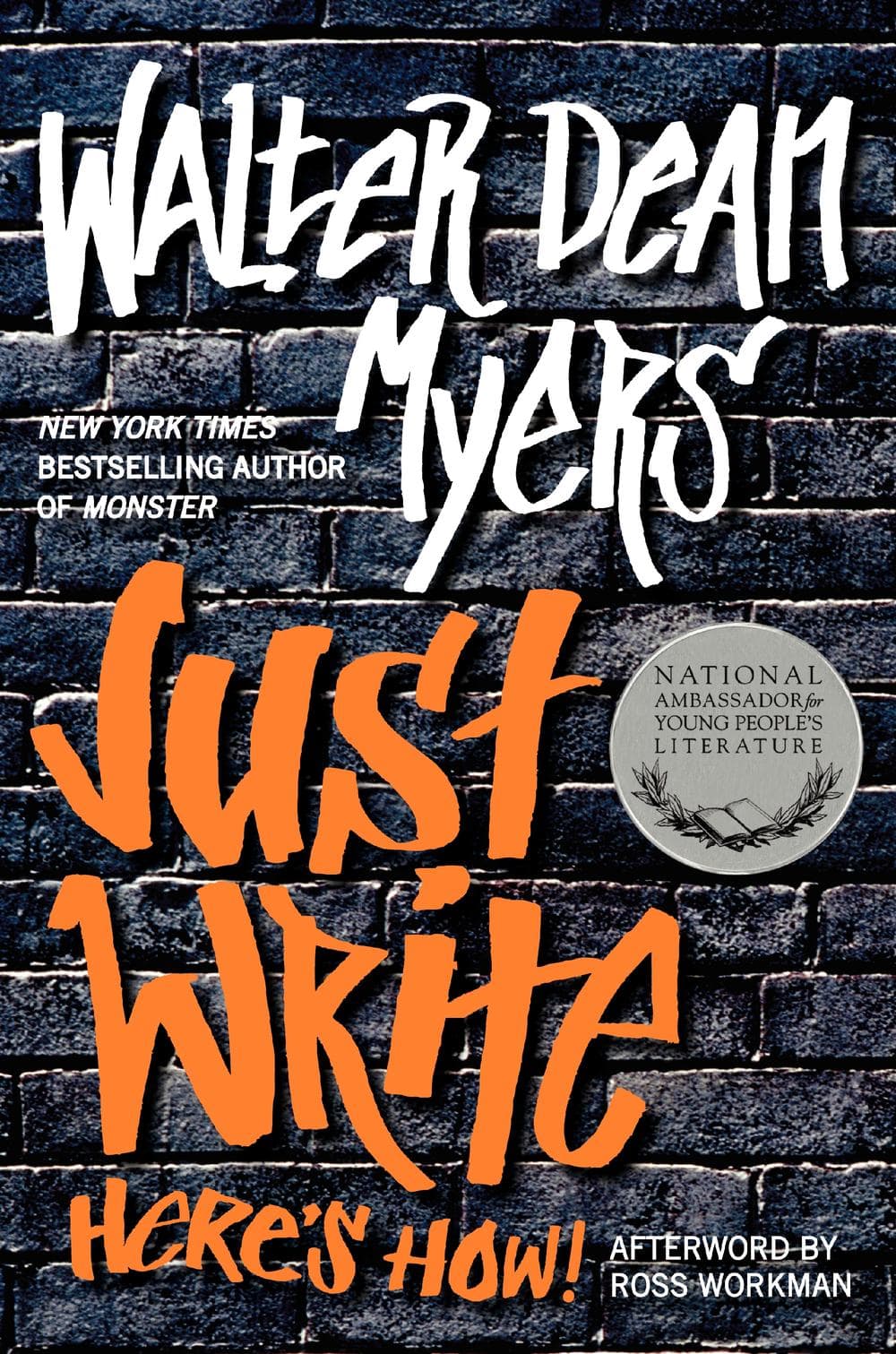

Myers now has more than 100 books to his name, including the New York Times bestseller "Monster." And in his latest book, "Just Write: Here's How!" he offers advice to his many young fans.

"I see so many of these kids who need an older person around them, a mentor. They need guidance and they need help," he told Here & Now's Robin Young. "If you give them any kind of guidance and help, they'll take to it."

Using His Life As A Template

In "Just Write," Myers gives would-be authors guidelines for how to develop characters and outline and write a story. As an example, he includes copies of his own notes from past books.

"I am determined to use my life as a template for these kids. If I can do this, so can they," he said.

Myers got this message across when he was visiting an elementary school, speaking to a class of second graders.

"A little girl pulled my pants leg and said, 'You know, you're not so much,'" he said. "I was taken aback at first, but then I realized that what she was actually saying was that I was an ordinary person that she could emulate, and that's what I want to get across."

Myers especially wants to show young people that they can succeed despite tough life circumstances.

"I was raised in a foster home with alcoholism and murders in my family. And yet I could rise above this. People need to see that," he said.

Advertisement

Book Excerpt: Just Write: Here's How!

By: Walter Dean Myers

We each are born into a history. We have a mother and a father, we have certain physical features and are born in a specific place. As writers, we get to invent different histories for our characters. To do this skillfully, we must seek to more deeply understand our own individual histories and their effect on us.

We each are born into a history. We have a mother and a father, we have certain physical features and are born in a specific place. As writers, we get to invent different histories for our characters. To do this skillfully, we must seek to more deeply understand our own individual histories and their effect on us.I was born with brown eyes and brown hair. My mother gave birth to me, but Florence Dean, my father’s first wife, and her husband, Herbert Dean, were my parents. There are aspects of my childhood that mirror the characters’ lives in my books. I was raised in Harlem, and many of my characters are teenage boys from urban neighborhoods. I got in a lot of fights at school, and some of my characters can be hotheaded and make questionable choices. Like my own family, a lot of my characters have difficult home lives and flawed role models.

In other ways, though, I was incredibly lucky. The Harlem of my youth was a cultural and creative hub. My difficulties in school often led me to my local library branch or to the solitude of my room, where I developed a deep love of reading and the written word. My parents—though not perfect—loved me and encouraged me in my intellectual pursuits.

When I visit juvenile detention facilities, I ask myself: “Why not me?” I didn’t have the easiest time as a teenager. I dropped out of high school and narrowly escaped arrest. I left home on a Monday, the twentieth of August 1954, to join the army. A few days later, the police came looking for me at my parents’ apartment.

Somehow, things turned around for me. I think a lot about how, and why. Maybe if I can figure out what went right, I’ll be able to help some of the young people who no doubt feel the same despair I did. Certainly some of it was luck: being given as a toddler to loving foster parents, being born in Harlem at a time in history when a rich culture existed there, even the police showing up after I’d left home. My characters, and many real-life young people, are not so lucky. I worry about these kids because I often think about my personal history and marvel at how easily things could have turned out differently.

Growing up, I made assumptions about the world, as all kids do, based on my immediate surroundings. I also made assumptions about myself. What I understood first was that I was black and poor. My adult role models were my father, who was a janitor, and my mother, who cleaned apartments.

I had a happy childhood for the most part, but I remember beginning to feel despair as I became a teenager. There wasn’t one specific thing that happened. It was a combination of bad things. When I was fourteen, my uncle was murdered. The brutal death of his brother sent my father spiraling into a deep depression during which he wouldn’t leave his room for days. My mother, who had always struggled with alcoholism, began to drink more heavily. Sometime around then, I started to understand that even though I was good at school and loved to read, college wouldn’t be a possibility for me because I couldn’t afford it.

Until I was a teen, I didn’t really understand that being poor could limit what I could do. I didn’t want to end up like my uncle or my mother, but I wasn’t sure what the alternative could be. I stopped caring about school. The limitations that I felt the world was putting on me made me angry. By the time I was fifteen, I was getting in trouble regularly and had to report to a city agency once a week for supervision.

I speak with thousands of young people around the country each year in middle schools, high schools, and juvenile detention centers. When we talk, I recognize in them—in you—a moment I remember in my own life. You might recall being asked as a child what you would like to be when you grow up. When you’re very young, growing up is something that will happen to you sometime in the future. Then there’s an almost imperceptible shift. All of a sudden, at some point, life stops being something that will happen to you and, instead, starts just happening. This is when reality sets in.

You look at the world around you and internalize it. You think of the world as being a part of you and see yourself as having a place in it. If the world around you happens to be a good place, you’re a very fortunate person. For me, and for many teens, the world around me was not a good place. The process of becoming a part of the world around me and the prospect of taking a place in that world made me lose hope. I didn’t know how I could overcome my circumstances, which looked bleak and very different from the idea of success my parents and teachers had given me as a child.

There was one place in my world that saved me from complete despair. The George Bruce Branch of the New York Public Library on West 125th Street became my home away from home, allowing me to escape the chaotic world around me. I could enter the library and participate fully, despite empty pockets. In the library stacks I could immerse myself in André Gide or Honoré de Balzac or Ernest Hemingway, and join a universe that would otherwise be denied me. There was no way I could have afforded to buy the books.

My circumstances often seemed insurmountable to me, but through reading I reached out for ideas that might help me escape them. The books I read showed me options other than those I saw reflected in my surroundings. They gave me new definitions for success in my life.

After the army, I held a series of low-paying jobs at a factory, a mailroom, a post office. I ended up working in construction, and was having a particularly trying day when I remembered something a high school teacher had said to me years earlier: “Whatever you do, don’t stop writing.” That afternoon, on my way home after work, I bought a composition notebook. I started writing in it and felt more alive right away.

I sent my poems, short stories, and some longer pieces out to publishing houses and received rejection after rejection. But I kept at it. I noticed that even though I didn’t have a college degree (I hadn’t even technically graduated from high school), I was able to get better and better jobs because of my reading and writing skills. Eventually, I entered a story in a contest run by the Council on Interracial Books for Children. My entry, Where Does the Day Go?, became my first published book.

What my experience has shown me is that my love of reading and writing was the key to overcoming despair. When I heard the world and my own voice in my ear, telling me I wasn’t good enough, books—reading them and writing them—kept some small bit of my self-esteem intact. They made me believe I could have a different sort of life than that of the adults I knew.

It wasn’t until years after my painful adolescence that I started writing regularly, and it wasn’t until years after that, that I began to make a living as a writer. But I see my success today as stemming from those moments spent lost in the world of a book, seeking hope at a time when I felt most vulnerable.

I’m not sure why I remember this part of my life so vividly, but I do. It’s why I love creating teenage characters, exploring how their inner lives and experiences reflect my own or differ from them. It’s why I love having an open dialogue with young people. It’s why I love writing for young people. There were books that helped me see an alternative, and I like to believe that I now write that kind of book.

I had a lot of chances to go down a bad path as a teenager, but instead I went to the library. The world inside my head was richly furnished with ideas I got from books, and provided an escape from the dangerous world around me.

Books saved my life, so I know it is at least possible for a book to perform that feat. I realize this probably happens quite infrequently. When I think about all the books that are written and published in the world, it seems even more unlikely that one of my books could end up in a position to do such a thing. I like to believe that my books will at least provide some entertainment. So, just in case, I keep on writing and writing.

I tell the young people I meet to read. Read everything you can, looking for the ideas that give you hope and expand your sense of what’s possible. If you can’t find something you’re looking for in a book, write it yourself. Try to get published. You have stories that other kids might need to read. You have stories that should be heard. Maybe a reader will find your book when the timing’s just right and it will help save a life. So just write.

Copyright (c) 2012 by Walter Dean Myers

Guest:

- Walter Dean Myers, author

This segment aired on June 5, 2012.