Advertisement

Eddie Huang Rejects 'Model Minority' Label

Eddie Huang has made a name for himself with his New York eatery Baohaus, his blog, as well as appearances on the Food Network, the Cooking Channel and Anthony Bourdain's "The Layover."

But growing up as the only Taiwanese-American in his Florida community, Huang felt continually like an outsider.

An incident in the school cafeteria when he was nine clarified things for him.

"This kid Edgar pulled me by my shirt, threw me to the ground in the lunch line and said 'Chinks get to the back.' And it wasn't that I realized, people made me realize what I was," Huang told Here & Now's Robin Young.

Eddie Huang's outsider status made him identify more with hip-hop artists like Tupac Shakur, rather than the model minority Asian stereotype. Through high school and college he got into fights, as well as scrapes with the law.

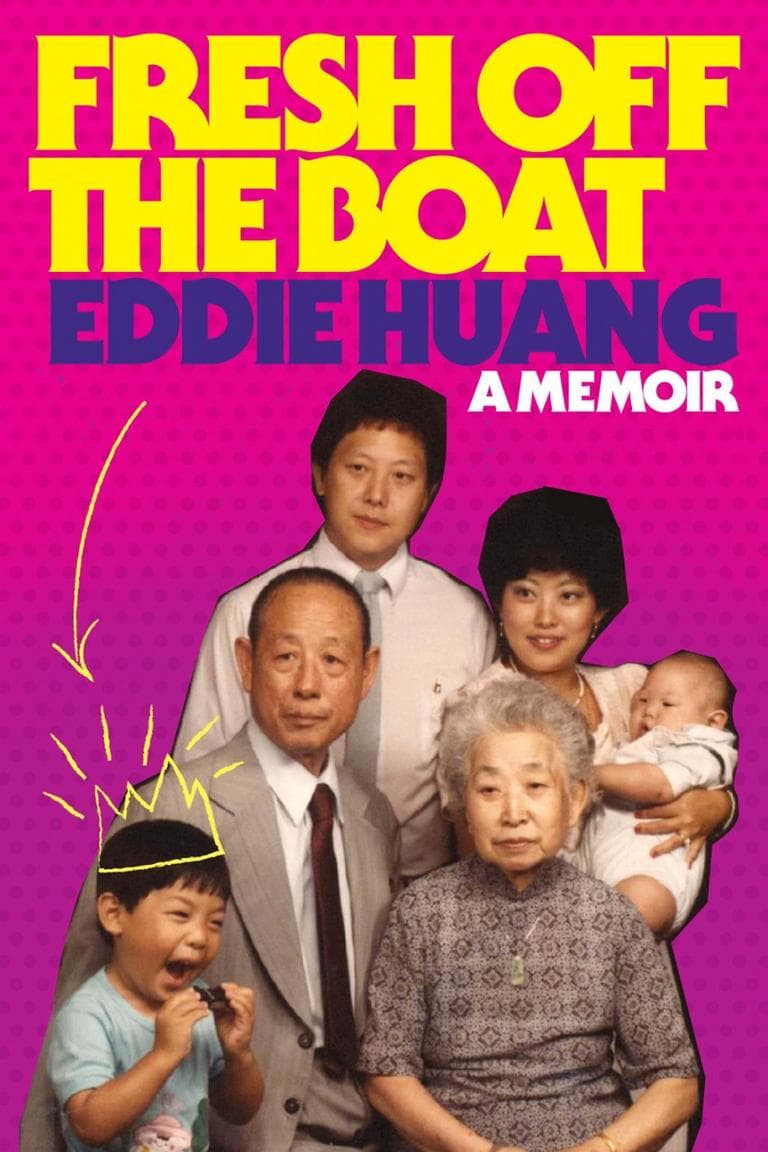

But eventually, Huang found success with his Taiwanese sandwich shop Baohaus and has now published his memoir "Fresh Off the Boat" (see excerpt below).

He says he wrote the book to encourage others not to accept the labels that are put on them.

- Eddie Huang's blog (Warning: As Huang told us, he's no angel. This blog contains adult content.)

Advisory: There is explicit language in this excerpt

Advertisement

Book Excerpt: 'Fresh Off The Boat'

By: Eddie Huang____

Chapter 1: MEET THE PARENTS

“The soup dumplings are off today!” Grandpa said.

“Should we tell the waiter? We should send these back.”

“No, no, no, no, no, don’t lose face over soup dumplings. Just eat them.”

My mom always wanted to send food back. Everything on the side, some things hot, some things cold, no MSG, less oil, more chilis, oh, and some vinegar please. Black vinegar with green chilis if you have it, if not, red vinegar with ginger, and if you don’t have that, then just white vinegar by itself and a can of Coke, not diet because diet causes cancer.

Microwaves cause cancer, too, so she buys a Foreman grill and wears a SARS mask because “oil fumes can ruin lungs,” says the woman who smokes Capri cigarettes and drives an SUV wearing a visor. That’s my mom.

I couldn’t eat with my mom; she drove me crazy. But she never bothered my grandfather. He was always above the trees. Like 3 Stacks said, “What’s cooler than cool? Ice cold.” That was Grandpa: a six- foot- tall, long faced, droopy- eyed Chinaman who subsisted on a cocktail of KFC, boiled peanuts, and cigarettes. Thinking back on it, my grandfather created the ultimate recipe for pancreatic cancer. At the time we had that lunch, he’d been battling it for a while, but we tried not to talk about it. That day, we just ate soup dumplings.

“It’s the meat, did they not put enough ginger? Mei you xiang wei dao.”

“Eh, there’s ginger, it’s just heavy- handed. Who cares, just eat them! The rest of the food is on the way.”

Xiang wei is the character a good dish has when it’s robust, flavorful, and balanced but still maintains a certain light quality. That flavor comes, lingers on your tongue, stays long enough to make you crave it, but just when you think you have it figured out, it’s gone. Timing is everything. Soup dumplings, sitcoms, one- night stands— good ones leave you wanting more.

The perfect soup dumpling has eighteen folds. Taipei’s Din Tai Fung restaurant fi gured this out in the mid- eighties. While Americans had Pyrex visions, Taiwan was focused on soup dumplings. My grandparents on my father’s side lived right on Yong Kang Jie, where Din Tai Fung was founded. To this day, it is the single most famous restaurant in Taipei, the crown jewel of the pound-for-pound greatest eating island in the world. Din Tai Fung started off as an oil retailer, but business took a dive in the early eighties and they did what any Taiwanese- Chinese person does when they need to get buckets. You break out the family recipe and go hammer. Din Tai Fung was like the Genco Olive Oil of Taipei. Undefeated.

The dough is where Din Tai Fung stays the hood champ. It’s just strong enough to hold the soup once the gelatin melts, but if you pick it up by the knob and look closely at the skin, it’s almost translucent. They create a light, airy texture for the skin that no one else has been able to duplicate. I remember going back to Din Tai Fung when I was twenty-seven and saying to myself, They’re off ! It’s just not as satisfying as I remember it to be! But two hours later, walking around Taipei, all I could think about was their f****** soup dumplings. Across the street from Din Tai Fung was another restaurant that served soup dumplings and made a business of catching the spillover when people didn’t want to wait an hour for a table. They were really close to the real deal. Like the first year Reebok had AI and you thought that maybe, just maybe, the Questions with the honeycomb would outsell Jordans. A false alarm.

Grandpa Huang put on for Yong Kang Jie and never cheated on the original. On the other hand, Grandpa Chiao, my mother’s father, had money on his mind and really didn’t have time for things like soup dumplings. He was the type of guy who would go across the street without thinking twice. He would be fully aware Din Tai Fung was better, but he was a businessman. He had things to do and never lost sight of them. Everything was calculated with my grandfather. On his desk, there was always this gold- plated abacus. Whenever something needed to be calculated, the other employees would use calculators, but Grandpa beat them to the punch every time. With his fingers on the abacus, he looked as slick as a three- card monte hustler. I loved hearing the sound: tat, tat, tat, rap, tat, tat, tat. After tapping the beads, he’d always reset them all with one downward stroke, whap, and out came the answer. He’d much rather save an hour, eat some perfectly fine soup dumplings, and go on his way.

Mom had other plans. She was my grandpa’s youngest and loudest child. Mom claims she was his favorite, and I can’t say I don’t believe her. Grandpa loved her because she was entertaining and full of energy. As a kid, she took the Taiwanese national academic exam and got into all the best schools in Taipei. After she came to America as a seventeen-year-old, she managed to graduate as the salutatorian of her high school, even though she barely spoke English. On top of that, she’s still the best cook in the family. My cousins love talking about things they don’t know about and everyone claims their parents are the best, but even the aunts admit my mom goes hard in the paint.

That day, my uncle Joe from my dad’s side was with us at Yi Ping Xiao Guan. I think he actually discovered the spot, because it was in Maryland, where he lived. Earlier that day, Grandpa had asked me where I wanted to go for my sixth birthday. He figured I’d say Chuck E. Cheese or McDonald’s, but Momma didn’t raise no fool. Chuck E. Cheese was for mouth breathers and kids with Velcro shoes. “I want to go where they have the best soup dumplings!”

“Where’s that?”

“Even Uncle Joe knows! Yi Ping Xiao Guan.”

I really liked Uncle Joe. He built three of the major bridges in D.C. and wore these big, thick black-rimmed glasses. I was into glasses, especially goggles, because Kareem wore them and he had the ill sky hook.

After we ate, I was kinda pissed with the s***ty soup dumplings. It was my birthday! Yi Ping Xiao Guan, you can’t come harder than this for the kid? Chuck E. Cheese can serve s***ty food ’cause you get to smash moles and play Skee- Ball after lunch. But all you have are soup dumplings! How could you f*** this up? Yi Ping Xiao Guan was like Adam Morrison: your job is to slap Kobe’s ass when the Lakers call time out. If you can’t do that, shoot yourself. As I sat there, pissed off, I saw a waiter pouring off- brand soy sauce into the Wanjashan Soy Sauce bottles. Corner cutting, bootleg, off- brand- soy- pouring Chinamen!

“Mom! Mom!”

“Eddie, stop it, I’m talking to Grandpa. Talk to Uncle Joe!”

If someone was talking to Grandpa, you couldn’t interrupt, but apples don’t fall far from the tree. My mom was the youngest and never followed rules in the family. She enforced them on everyone else, but she never followed them herself.

“MOOOMMM! Listen!”

“Huang Xiao Wen!”

That was the signal. Black people use the government name when s*** hits the fan, and my family would bust out the Chinese. It hurt my ears to hear the Chinese name. Not only did it seem louder and extra crunchy, but it usually meant you were about to get smacked the f*** up. Luckily, Uncle Joe was a nice guy who actually thought it was possible that a child might have something important to say.

“Uncle Joe, I know why the soup dumplings are bad.”

“Really? Tell me!”

“Look over there: the waiter is putting the cheap soy sauce in the bottles. They must be using it in the dumplings, too.”

“Genius! Genius! Aya, Rei Hua, Rei Hua, zhu ge Xiao Wen tai cong ming le!”

Rei Hua was my mother’s Chinese name, so Uncle Joe got her attention when he used it.

“Eddie figured it out. They’re using that cheap heavy soy sauce now. Look over there, he’s putting it in all the bottles!”

“Oh my God! Too smart, too smart, I told you, this one is so smart!”

“Whatever, Mom, you never listen!”

“Shhh, shhh, shhh, don’t ruin it for yourself. You did a good thing, just eat your food now.”

I think my mom is manic, but Chinese people don’t believe in psychologists. We just drink more tea when things go bad. Sometimes I agree; I think we’re all overdiagnosed. Maybe that’s just how we are, and people should leave us alone. My mom was entertaining! If you met my family, you’d prescribe Xanax for all of them, but then what? We’d be boring.

At any moment, I was around my younger brother, Emery, my aunts, my uncles, my cousins, or my parents. We ate together, went shopping together, and worked together. Sometimes five of them, sometimes twelve of them; on weekends, it was anyone’s guess. We’d pick an aunt’s house and you’d see a line of Cadillacs, Lincolns, and Toyotas form down the street.

Our family counted all the aunts and uncles from both sides as one team, so even if you were the oldest in your family, you might be second or third in the larger bracket. Got it? Good. So, #1 Aunt lived in Pittsburgh, where that side of the family had a furniture store. She would come down every once in a while with her kids and they were always friendly. We loved that side of the family because we saw them only three or four times a year. #2 Aunt was my mother’s oldest sister and she made the best ti-pang: red cooked pork shoulder. Her husband, Gong Gong, was a really funny guy. He didn’t speak English, so he’d always test my Chinese, check my biceps, shoulders, triceps, and then ask to arm wrestle. Gong Gong was a funny dude, bent over all his nephews, examining them like they were entries in a dog show.

#3 Uncle was my cousin Shupei’s dad. I never spoke to him ’cause there were always fifty or sixty people in the house when he came, since it was a big event. He lived in Pittsburgh, had four kids, and they all traveled together in packs. It was awesome when they visited. Shupei and his cousin Schubert, cool dudes who played ice hockey and poker. They were also huge, the first six- foot- three Chinamen I’d ever seen. As a nine- yearold, I’d tell myself I had a chance at going NBA if I grew as tall as they did. Also, Shupei’s wife was white, which gave me hope that I didn’t have to date someone from Chinese school.

#4 Aunt was my mom’s sister. She was crazy and, without any notice, she would say things like “Look how fat you are!” or “You are really stupid, do you know that?” As a kid, I stayed as far away as possible from her and her brother, Uncle Tai, because they were like Boogie Man and Bride of Boogie Man. As I got older though, #4 Aunt became a lot nicer and my brothers and I finally understood: it wasn’t her. My mom was the one telling #4 Aunt about how me and my brothers were acting up. As a favor to my mom, she took on the role of enforcer. She was the first person in our family to figure out how to make cheesecake. For some reason, she had more interest in American food than the rest of us did. Ironically, she also made the best American Chinese food: fried rice.

Then came #5 Aunt, also called Aunt Beth; she was my cousin Allen’s mom. Then came my cousin Phil’s mom, who never took an American name. Next was my Uncle Tai and lastly was my mom, who everyone called “Xiao A- Yi”— Little Aunt. Phil, Allen, and their moms were my closest family.

Advertisement

Aunt Beth put out a good dinner when the family got together at her house on the weekends. It was balanced. Always two vegetables depending on what was in season— it could be Xiao You Cai or sautéed kong-xin cai (Chinese watercress, literally “hollow heart vegetable”), which is my favorite vegetable. She liked making tomato and eggs, plus some sort of shredded pork stir- fry with either cured tofu or beans, and chicken soup. Aunt Beth was a great host— she served a balanced meal, and let me watch sports before the older people took over the TV to sing karaoke.

I thought my cousin Allen was the coolest dude. He was three years older than me so he knew about everything just before I did. When we went to the mall, he showed me purple Girbaud jeans. He was the first to get a CD player and we always listened to Onyx’s Bacdafucup together. If his mom had to pick him up from detention at school, I went to go get him, too. Sometimes he’d treat me like a burden, but I looked up to him. I was learning.

My other cousin Phillip was my best friend. He was only a year older than me, but he really took on the role of older cousin. He was the kindest person in the family and smart, too. He knew something about everything, but wasn’t afraid of doing dumb s***, either. Our favorite thing to do was to watch WWF together on Saturday mornings at Aunt Beth’s house, get hyped, and try out moves in the pool, where they’d body- slam me, causing me to immediately puke the tomato and eggs I’d just eaten into the water.

We fought a lot, made fun of each other constantly, but it was a good time. It was always chaos in the living room when our whole family came over, so Allen, Phillip, and I would retreat downstairs after dinner and play Tecmo Super Bowl or Mike Tyson’s Punchout. We’d stay in the basement for hours and every once in a while, they’d send me up to get drinks and snacks. I’d go into the dining room, which was only separated from the living room by one step. A false divider. Although everyone else had gone to the living room for karaoke, one person always remained on the dining room level: Grandma. She’d sit there in her wheelchair and make birds out of Play-Doh. I’d come up to get drinks and see her alone, so I’d hang out with her for a minute. All of us would keep her company at one point or another in the night.

Grandma had bound feet. She couldn’t walk, but in the house, she was always present, always watching, an anchor in the middle of the room. No one ever argued around Grandma and we all put on our best faces for her. We revered her, but we also pitied her. The uncles and aunts claimed her feet were “pretty” and that binding was just how things were done in the old days. If you went into Grandma’s bedroom, you’d see her little shoes all lined up by her closet, and the Chinese people that visited were always saying nice things about them. Most of the shoes were silk and had intricate patterns or embroidery. Guests gushed over the stitching, but I thought the whole thing was gross. The little shoes ruined Grandma and I hated them.

We weren’t supposed to see Grandma’s feet, but I snuck into her room once when her nurse was washing them. They were deformed, mangled like potato roots. I was so angry— I couldn’t believe they did that to Grandma. But she never complained. I would ask my mom, “Can we fix Grandma’s feet?” She said no, but I didn’t believe it. My grandma on my dad’s side had her feet bound for a while, too, but luckily, her brother went to school outside China in the early 1900s and the first thing he did when he got back was unbind her feet. That grandma lived to 101 years old, did tai chi every morning at six, and got to live her life. I wanted that for this grandma, too. Without ever reading Audre Lorde or Teresa de Lauretis, I understood how s***ty it was to be a Chinese woman and really felt bad for them, whether they were my aunts, Mulan, or Grandma. Especially Grandma.

In China during the war, the people had to stand in long lines for food and water. One day, this guy tried to cut the line and my grandpa jumped him. While they fought, Grandma got so nervous she had a brain aneurysm and nearly died. She lived through a lot but somehow always seemed content with the world. Grandpa, Uncle, Mom, Aunt Beth, they all had bad tempers. There was never a dull moment or a plate that lasted longer than three months. But even when people threw plates or staplers or bowls of rice at each other, Grandma stayed calm. She never stopped smiling. One of the best ways to stop the fights between my mom and Aunt Beth was to wheel my grandma into the room. Everyone was too embarrassed to argue in front of her. It was like putting a lid over the hot pot when Grandma came around. She didn’t have to say anything. We all knew her story and if she could stay calm, we should, too.

My mother’s father had six kids. After the Cultural Revolution, the family fled to Taipei. My grandma was pregnant with my mother at the time so my mother was the only one born there. M.I.T.— Made in Taiwan. My grandpa and grandma were broke and made a living selling mantou on the street, just like Kossar selling bialys or Schimmel selling knishes. The easiest way for Americans to make sense of Chinese history is to compare everything to Jewish history. There’s an analogue for everything. Torah: Analects. Curly sideburns: long ponytails. Mantou: bagels. My family sold fresh mantou every morning. People would buy them on the way to work and eat them with hot soy milk. Back then, most didn’t have money for meat so you just ate the bread alone. Grandpa would bring the whole family out to do business together every day. The youngest daughters were charged with selling the mantou because pretty girls represented the best chance to close. There was a man from Hunan that would come by like clockwork. One day, he lingered and asked to speak to my grandpa. Turned out that he owned the only textile factory in Taipei at the time and he really liked our family. They were there on time, rain or shine, and the mantou were always hot. He respected the family hustle.

The family that was working for him at the textile factory hadn’t shown up for an entire week. He needed new workers, so he offered to have my grandpa bring over the whole family and get to work. This was one call my grandpa didn’t need the abacus for. As my family likes to tell it, they dropped the mantou on the street and went straight to the factory. They busted ass, learned the trade, and a few years later my grandpa opened his own factory. Eventually, he became one of the first Taiwanese millionaires. They ended up staying in Taiwan about seventeen years, then came to America and opened a furniture store, Better Homes, in northern Virginia. Why leave a country when you’re on top? Whether it was another communist scare or the even greener pastures in America, no one ever gives me a straight answer. (The only thing anyone can agree on is that they still miss the island.)

WHEN I WASN’T in school, I was at Better Homes, in the office where all the aunts worked. Better Homes was a quintessential eighties mini-mall white box with a square glass front. Built to sell. I spent the first five years of my life handcuffed to a playpen in the middle of this mini- mall furniture- store office. Before I even knew about guns, I was trying to shoot myself.

Outside the office was the showroom, which is where the action was. I liked it. My mom was the only one of her sisters to go to college, where she trained as an interior designer. She had a big part in laying out the store and I thought she did a pretty good job as I toddled through the aisles. When business was slow, I’d go around and test out the couches, poke the mattresses, and shake hands with customers. I was working. My mom would lose track of me most days so she’d come out to the showroom and shout my name.

“Eddie! Where are you?”

“Mom, I’m over here! Come sit in this chair.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Please, relax, sit in this chair.”

“Eddie, I’m busy, why do you want me to sit in this chair?”

“Just sit in the chair, Mom! I want to sell you something.”

“You’re crazy!” she’d say, laughing. “Why do you want to sell me something?”

“Because I’m a businessman!”

All day, I saw my dad or my grandpa sit with customers on couches or chairs, and within twenty minutes, cash was exchanging hands and furniture started moving. I wanted to be like them. They got to wear suits, customers loved them, and they didn’t have to work in the white box. Grandpa had a big office separate from the aunts and so did my dad. I figured, if I could sell, I could escape.

I was too young to be a businessman, but Uncle Tai had a way out for me. One day, I was wandering around the sales floor looking for my dad, when I ran into Uncle Tai.

“Hey! What are you doing on the floor!”

Uncle Tai was always yelling at the kids.

“Looking for my dad.”

“He’s busy! Go back to the office.”

“I don’t want to go to the office, it’s boring.”

Most of the cousins didn’t talk back to Uncle Tai. He was notorious for disciplining kids, but he knew not to touch my brother, Emery, and me. We were Louis Huang’s kids, not his.

“Hmmm. Do me a favor, then. I need a pack of cigarettes, Marlboro Red.”

I’d seen people get cigarettes before at the Sunoco next to Better Homes, and thought nothing about it.

“Cool. Can I get a grape soda, too?”

“Yeah, if you get me the cigarettes, you can get a grape soda.”

I was dumb excited. Grape soda was my s***! My favorite part was that you got Grimace lips after drinking a can of it. It was a sunny day outside and it must have been the summer. As soon as I opened the door, DMV* humidity just hit me in the face. I walked the 150 feet to Sunoco, got on my tippy- toes, knocked on the window, and waited for the attendant to get on the microphone.

Brrr. “Can I help you?”

I was barely tall enough to talk into the microphone, but I reached up, pressed the button, and just leaned toward it as I spoke.

“One pack of Marlboro Reds and a grape soda, please!”

Usually, the attendant would just grab your stuff and put it through the window, but he opened the door and came outside.

“Who asked you to get them cigarettes?”

I could tell something was wrong.

“No one. I like Marlboro Reds.”

“You don’t like Marlboro Reds. Who told you to get them?”

“No one.”

He looked away and thought to himself. After a few seconds, he went back in the Sunoco, grabbed me a grape soda, held my hand, and walked me back to Better Homes. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to deduce that the seven- year- old Chinese kid had wandered over from Better Homes and that it was Uncle Tai, the pack- a- day smoker, who sent me. We walked in the main doors of Better Homes hand in hand. I was nervous. I started drinking the soda. I knew I’d done something wrong, but he gave me a grape soda so I was a bit confused. Was it my last meal? Was I being poisoned? I stopped drinking the soda.

That’s when he found Uncle Tai.

“You sent this kid to buy you f******cigarettes!”

I remembered that word. My parents said it all the time right before someone would start throwing chopsticks.

“So what? It’s right next door, no big deal!”

“No big deal? This kid can’t be seven years old and you want him buying cigarettes? The hell is wrong with you!”

After that, I stayed away from Uncle Tai. My dad never got along with him anyway. He was Grandpa’s only son, but there was always an uneasiness because Pops worked more closely with Grandpa. In a lot of ways, Uncle Tai was Sonny to my father’s Michael. (Still trying to figure out who Fredo was.)

One day at Better Homes, Grandma was coming to eat with us after work. I was really excited: we were going to this Vietnamese shack down the road. We rarely ate anything besides Chinese, Mexican, and Chesapeake Bay seafood. When we craved it, my mom would take us to Roy Rogers, but Grandpa had high cholesterol, so we tried to keep him away. This Vietnamese place was unstoppable. They did a lot of things well: spring rolls, summer rolls, pork chops, and crab patties.

From the outside, it looked like a crane literally had picked up this wooden shack from Hanoi and dropped it into the DMV. The front door was hanging by one hinge and the wood was weathered and cracking. As soon as you opened the door, you got hit by the smell of caramelized meat sizzling on the grill. Even at seven years old, I was obsessed with Vietnamese pork chops and quail. The combination of white meat, sugar, and fish sauce on the grill gave me the screw face every time. It was just f***in’ mean. Good food makes me want to hit a punching bag like, Dat’s right motherf***er. You done did it there.

I liked this place because, even if I couldn’t exactly describe it at the time, they clearly brined their meat. It was juicy, bursting, and flavorful, without being overly salty.

The temperature of the grill is also important. Some people think you should barbecue slow and low on a grill. I disagree. If you’re going to do slow and low, do it with indirect heat in a smoker. The only time I like a grill is for high heat searing with brined meat: half- inch pork chop, get a nice seared crust, three minutes on each side, and serve it ready to burst. As soon as your fork touches the meat, it just gives.

Not only did this place have amazing pork chops, but they did quail, which most restaurants don’t bother with anymore. It’s not easy to do. Quail is a small, tender cut of meat and if not done right, it can get dry and sinewy very quickly. There’s also a slight gaminess, but that’s what I really loved about it. That, and picking the meat out of the bone crevices. Their quail had a very light marinade; they let the meat speak. Of course, there was lemongrass, sugar, and fish sauce, but little else. Maybe some garlic, but not enough to overpower anything. The flavor really came from the sugar caramelizing on the grill, the hint of lemongrass, and the essence of the fish sauce. I wish I could remember the name of the joint. Best Vietnamese I ever had.

My brothers liked the place, too. I have two brothers: Evan and Emery. Emery was born three years, six days after I was and Evan was born two years and seven months after Emery. Until the age of eight or nine, I really saw my brothers as having a single purpose: ordering things I’d like to try but didn’t want to order for my main dish. They hated me at dinnertime. I’d tell them what to order, eat their food before I ate mine, and if I liked theirs better, I’d try to trade. My mom was the one who always complained.

“You are always eating Evan’s food! Eat your own, Eddie.”

“Yeah, he eats mine, too, Mom!”

“I know, Emery, everyone can see he’s eating everyone else’s food! His knees look like grapefruits.”

“Whatever! You are cheap and don’t order enough food, so I have to eat everyone else’s.”

My brothers both developed techniques to prevent me from bumming off their plates. Emery would poke me when I was trying to eat, or he would touch all his food with his hands so that I wouldn’t want to eat it anymore. Evan, on the other hand, was a f***ing momma’s boy. He’d cry to my mom.

“Mooommm, this is my favorite food and Eddie keeps eating it!”

“Eddie! Stop eating his food, pi par tofu is his favorite!”

It worked every time. This a**hole had so many favorites we lost track: pi par tofu, radish cake at dim sum, Yan Yan chocolate sticks. He was a genius and a snitch. But we still got him back.

One time my Mom bought us Nickelodeon Gack and then left us alone for five hours. Bad idea. Gack was this nasty, goopy, dense, sticky green slime that had a consistency like warm Laffy Taffy. Emery and I would put little pieces of it in the carpet just to see if we could get it out, but we were left with polka- dot green carpet. After realizing the power of Gack, we decided to f*** Evan up. We wrestled him to the ground and put all the Gack in his hair. He started crying hysterically trying to get it out and pulled out mad hair in the process. This was before cellphones, so he couldn’t call my mom. He thought he was going to die. It was great. But Mom did eventually come home.

“WHAT ARE YOU BOYS DOING?”

“Mom, they said they were going to ‘f*** me up’!”

“No, we didn’t, he f***ed himself up.”

“No one is f***ing anyone! Who taught you to f*** people up? Did you put all this Gack in his hair?”

“YES, they did it, Mom!”

Emery and I were loving it. We knew we were going to get our asses kicked, but watching the snitch cry was the best. And as long as Evan had a headful of Gack, we knew Mom would be preoccupied.

We weren’t happy for long.

Mom poked around at the Gack for a few minutes, went to the kitchen, and came back with a bottle of Heinz white vinegar. She took Evan to a bathtub and poured the vinegar over his head. Instantly the Gack started to bubble and dissolve.

“Oh, s***.”

“Run.”

Without even waiting for my mom, Emery and I took off up the stairs to his room. We always hid in his room. Even though I was the oldest, we liked hanging in Emery’s room best. His room had more light, action figures, and goofy patterned furniture. We drew our master plans to escape on his desk, made forts on the floor, and went out on the roof through his window.

In those days, we were all about getting away. My parents got married young, after knowing each other for only three months and Mom had me when she was twenty. You know the deal. Mom likes to say we grew up together. When she had problems with Dad, we’d ride around in the car and she’d tell me all about it, even though I wanted nothing to do with it. I was seven; how was I supposed to play Dr. Phil?

“We’re running away, Eddie!”

“To where, Mom?”

“Away from your dad! He’s crazy.”

“You always say that and we always go back home.”

“This time is different. I’m not going back anymore.”

“Emery and Evan are still there.”

“Shut up!”

She knew she was going back.

My dad was a tough dude. Didn’t waste a word. He was firm, smart, and pretty damn funny, too. The worst part for my mom was that when she wilded and tried to make fun of my dad, he had all the jokes. She was from the more suburban and sheltered part of Taipei so he called her shambala (country bumpkin) or a fan tong (rice bucket). He was a hilarious dick.

When they fought, we’d all lock ourselves in Emery’s room. Evan would get scared, so we’d make forts and read comics. My mom only ever bought us three comics (Uncanny X- Men #1, Punisher, and X- Factor) so we just took turns reading them over and over. From those three comics we created our own characters, gave them special abilities, and then played out scenes from the worlds we created ourselves. The Punisher was my favorite, a bad dude with good intentions. Any means necessary to do the right thing. I liked that blurring of good and evil. At an early age I realized, like Black Star said, “Things ain’t always what they may seem.”

When I was only five, my mom got in a fight with my dad at dinner.

“You told me you’d take me to the mall!” she yelled at him. “You promised! You always break your promise!”

“I’m too f***ing tired, OK! It’s six o’clock. I don’t want to go on the Beltway and fight traffic.”

“Loser! You’re a loser! Never keep a promise!”

Then he flipped the table. Food went flying everywhere. Plates broke. That’s when Mom went Connie Corleone.

“Yeah, break all the plates! We have tons of money, just break the plates!” Dad screamed.

As Mom started kicking plates and Dad walked away, I picked up a pair of chopsticks. Held the s***s tight.

“Mom . . .”

“What!?”

I showed her the chopsticks.

“I’ll go fight traffic with you, Mom.”

To this day, that’s her favorite story. I was always ready.

SHORTLY AFTER THAT birthday dinner at Yi Ping Xiao Guan, my grandfather passed away. We knew it was a matter of time, but you’re still never ready. My parents loaded us up in the car and we all had to wear suits. No one said a word. The limousines met at Grandma’s house on a cold fall day. Gray skies, no breeze, just kind of frozen. It wasn’t the cancer that killed Grandpa. He ended it in the basement. The illness was terminal; the pain was too much. My mother told me what happened, but none of the other cousins knew. I don’t know why she told me, but there’s no reason not to. I dealt with it. Quietly. And didn’t speak a word of it to anyone, not even my brothers. I had a feeling my family would never be the same without Grandpa at the top. I remember when my grandma died years later, everyone was hysterical, crying, loudly mourning. With Grandpa, it was silence. I can’t say why; maybe it had to do with the suicide. Or perhaps we knew he didn’t want anyone to cry for him. He never really needed our sympathy. Or maybe everyone was worried about themselves. Mind on the money.

What happened after is “adult business.” Suffice to say, primogeniture was alive and well in 1980s Chinese families. My father decided not to work for Uncle Tai managing the furniture store after Grandpa passed. My dad had loved Grandpa and he always says that Grandpa was his best friend. But Dad was a grown-ass man; he never would have taken orders from anybody but my grandpa. So when my grandpa passed, he went solo. Mom loved her family, but she understood why my dad struck out on his own. My dad opened up his own store in the Fair Oaks Mall. He became the first Thomasville furniture dealer in Virginia.

Coming over as a broke Taiwanese immigrant, he was really proud of himself and I was, too. He somehow saved up enough to get the shop going, but things went south quick. Within two years, the store folded and my dad left home. My parents were constantly fighting, because we had lost everything and the court froze our bank account. For a while, it looked like my parents might even get separated. It was one of the worst times in my life. Even as a seven-year-old, I knew exactly what was going on. The winter of 1989 was the worst. My father decided to take a new chance to make it happen for himself in America. He left the DMV and went down south to Orlando with his friend Lao Zhou, where he got a job as a line cook at Steak ’n Ale and L&N Seafood. He wasn’t really trying to kick off a career as a line cook. What he wanted to do was get into the restaurant business. He knew some people who would help him get on his feet, and restaurants were going up all over the place in Orlando. Landlords would give you a restaurant with no key money and three months free rent if you’d sign a lease. It was a theme- park and sunshine- fueled boomtown. After working a few weeks as a line cook, taking notes and watching how they set up the operation, my dad signed on his own spot: Atlantic Bay Seafood.

I couldn’t believe it. One second we had a frozen bank account and no furniture store; the next, my dad had gone down south and he and Lao Zhou had a restaurant. Mom wasn’t convinced by Dad’s reports. She kept us back in Virginia while she went to go visit Dad, to make sure he really was a success. It was Thanksgiving weekend. #4 Aunt moved in to babysit us for the week and all we ate was Domino’s Pizza every single day. For years after that, I didn’t want to see another f***ing Domino’s Pizza box ever again. She wouldn’t let us play video games and we weren’t allowed to go outside or stay up past 9 p.m.

One night, I crept out of my room. I usually never did that, because we lived in a one- story house with a long hallway that looked like it had no end and I was scared of the dark. There was one night-light on the right side so I put one hand against the wall, held my breath, and walked toward the light. I got to the living room, turned on the television, and put it on mute so #4 Aunt wouldn’t wake up. Surrounded by Domino’s boxes, I watched the news and they kept talking about this wall coming down. On either side, people were going nuts. Some were banging on the wall, they were holding signs, others climbed on top of the wall. I saw families. I knew they were families, because they were embracing, hugging, crying. I figured they hadn’t seen each other for a really long time and I started crying, too. I just wanted to see my dad.

* D.C., Maryland, Virginia

Excerpted from the book FRESH OFF THE BOAT by Eddie Huang. Copyright © 2013 by Eddie Huang. Reprinted with permission of Spiegel & Grau, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

Guest:

- Eddie Huang, chef, owner of Baohaus and author of the memoir "Fresh Off The Boat." He tweets @MrEddieHuang.

This segment aired on March 21, 2013.